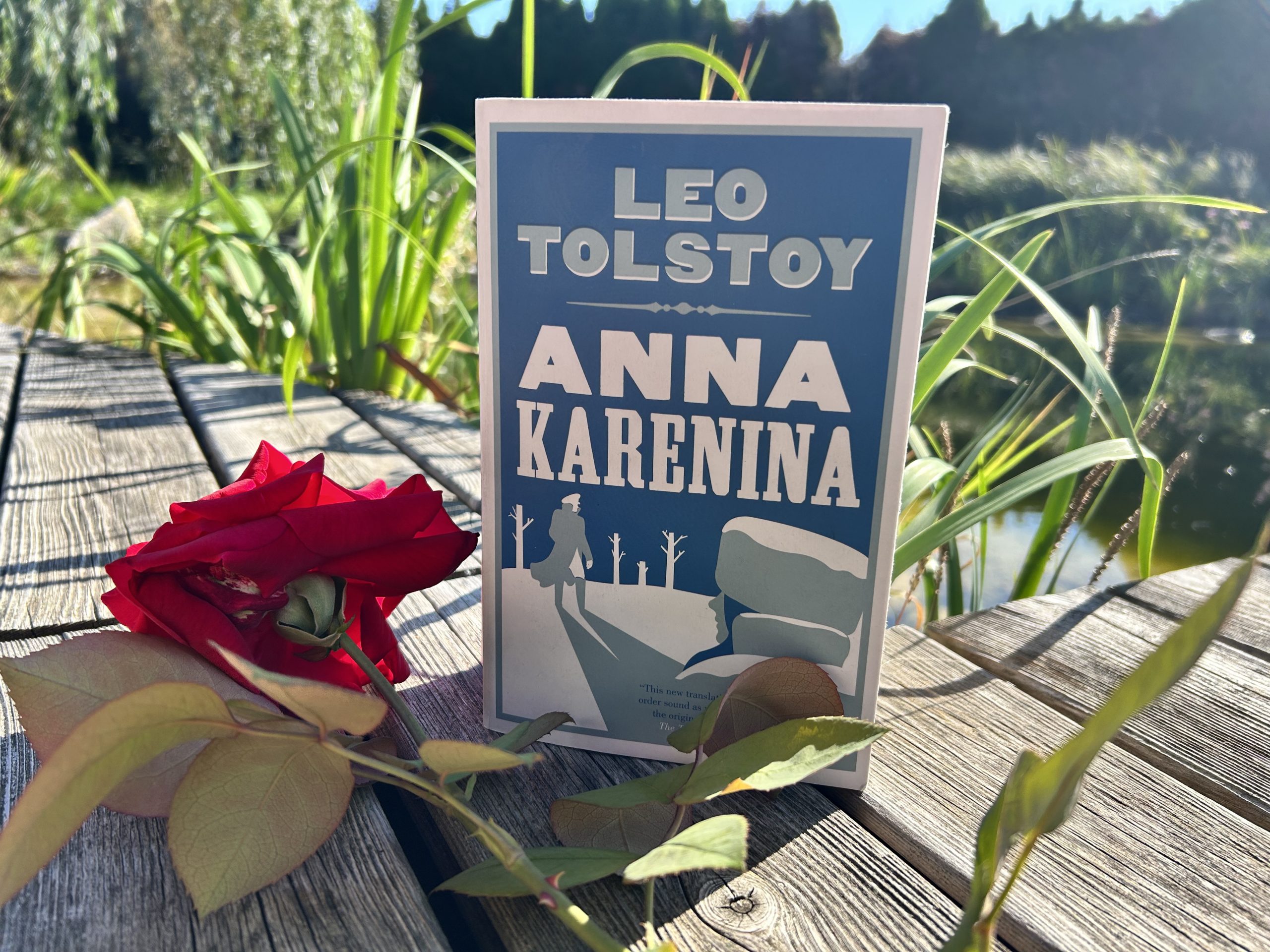

It took Leo Tolstoy five years and several draft versions until he came up with the Anna Karenina we read and love today. Unfortunately, some of us can’t read and love it in the original Russian, so we have to rely on one of the widely available translations. For the English version, I chose the Alma Classics 2014 edition, translated by Kyrill Zinovieff and Jenny Hughes and for the Romanian version, the Univers 1980 edition, translated by Mihail Sevastos, Ștefana Velisar Teodoreanu and Alecu Donici. The English version felt more precise, if also more laboured, but in these two languages I lived in two worlds. Very similar worlds, divided by nuances and reunited within my life experience and my ability to understand people. And even if some of us will never be able to read the novel in Tolstoy’s language, we can’t fail to sense the immense force of life which flows through it. Tolstoy didn’t keep his usual diary in the years when he actively wrote the novel, and maybe that’s why it almost feels like a private life fragmented into tens of other lives captured together in a jewellery box.

The novel has two major narrative threads that, like the intertwined strands of the DNA structure, form a pattern of life. One thread follows Anna Karenina, the spirited and lively heroine who gives up everything for a forbidden love with Alexei Vronsky, a cavalry officer who also abandons his career for Anna’s love. Meanwhile, Alexei Karenin, a high-ranking official torn between maintaining social relations in the turmoil of a broken marriage, tries to find the strength within himself to grant Anna forgiveness and freedom. The other thread centers on Konstantin Levin, a landowner who feels out of place in the high social circles and its sterile salon discussions and looks for meaning in the countryside which offers him a different perspective on the lives of ordinary peasants. Kitty Shcherbatskaya, Levin’s romantic love, is a young idealist who, after experiencing disappointment in love, finds purpose in her marriage to Levin and their child.

The phrases I wrote in the previous paragraph in an attempt to summarize the novel are less than a faded shadow of how it actually feels to live inside of it for six months. It is not about what “it’s about”, but about the people, with their struggles and shortcomings, their dilemmas, their contradictions, their lives. Virginia Woolf gives in her essay ‘The Russian Point of View’ a short overview of Chekov, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, the three major 19th century Russian novelists. For her, the endings of Chekov’s stories strike like nothing else, Dostoevsky dives into the depths of the human soul, but it is Tolstoy who has the eye for detail which makes up the authentic life in his novels. Of all the three writers, “It is Tolstoy who most enthralls us and most repells”, writes Woolf.

I think that what breathes life into the novel is how we get to know characters both from external observations and through their internal experiences, as well as the several perspectives through which we see an event. Probably the most telling example is the scene of the horse race in part two. Karenin is already aware of the affair between Anna and Vronsky and had asked her to at least keep up the appearance of an undisturbed marriage when in society. But the horse race is not just a social event. For Karenin, Anna and Vronsky, it is the breaking and making of a new life. Vronsky is taking part in the race and his perspective is highly dynamic: “His excitement, his delight in and affection for Frou-Frou [his mare] were growing stronger all the time”. Anna is aware of both men: “Two men, her husband and her lover, were the two centers of her life and, without the help of her external senses, she felt their proximity”. Karenin’s eyes are glued to Anna’s figure: “He peered again at her face, trying not to read what was so clearly written on it, and against his will he was appalled to read on it what he did not want to know”. Reading this scene, an objective perspective on the horse race becomes impossible. The three characters are very subjectively involved in what unfolds in front of them.

Anna is probably the one who experiences the scene most intensely. She is worried about Vronsky and refuses to let herself be pinned down by the conformity which her husband asks of her. The very first time we meet her, we are within Vronsky’s point of view, and he can’t fail to see the barely restrained life which bubbles up to the surface: “In her brief glance Vronsky had had time to notice the suppressed animation which played on her face. She deliberately extinguished the light in her eyes but it shone, against her will, in her scarcely perceptible smile”. Through her affair, Anna can shake off the restraints of the loveless marriage with Karenin and finally live, even as she is paying the ultimate price for it.

If Anna’s life is intense passion, Levin’s storyline offers a counterbalance to it. His ideal of love is traditional and romantic, and his pursuit of marrying Kitty is almost a satire on the classical marriage plot of 19th century English novels. In one moment at the skating rink in part one, Levin is anxious to meet Kitty, but also eager to confess his love: “This is life, this is happiness. Together, she said, let’s skate together. Shall I tell her now? But after all that’s just why I’m afraid to tell her, because now I’m happy, happy if only in hope”. But marriage is for Levin just something people do and his future wife, a reimagining of a “delightful and sacred ideal of womanhood”. He seeks meaning in the raw rhythms of rural life, seeks to step over the boundaries of class, while at the same time he cannot defeat the materiality of his own condition as landowner.

In Anna Karenina Tolstoy seems to conjugate different forms of how life can be lived – lively and passionately, like Anna, who sacrifices everything to pursue her desires, but also reflectively and in doubt, like Levin, who continues his own personal quest for meaning, even while his family life is peaceful and settled. I don’t think Tolstoy asks us to be the judges of what is “better”, but he does confront us with a larger question. Why live?

your thoughts?