I love literature which mingles with other arts. Lately I’ve been noticing how music pops up in the books I read, but also painting, theatre, writing, opera or photography catch my eye. I really love how all these different forms of art combine under the umbrella of literature and illuminate shaded parts of being human. Because words can’t tell everything, can’t be everything. When confronted with feelings for which we even have no words, only music or painting can help us reach further. This is when surprising realizations, both for character, and for reader, come to light.

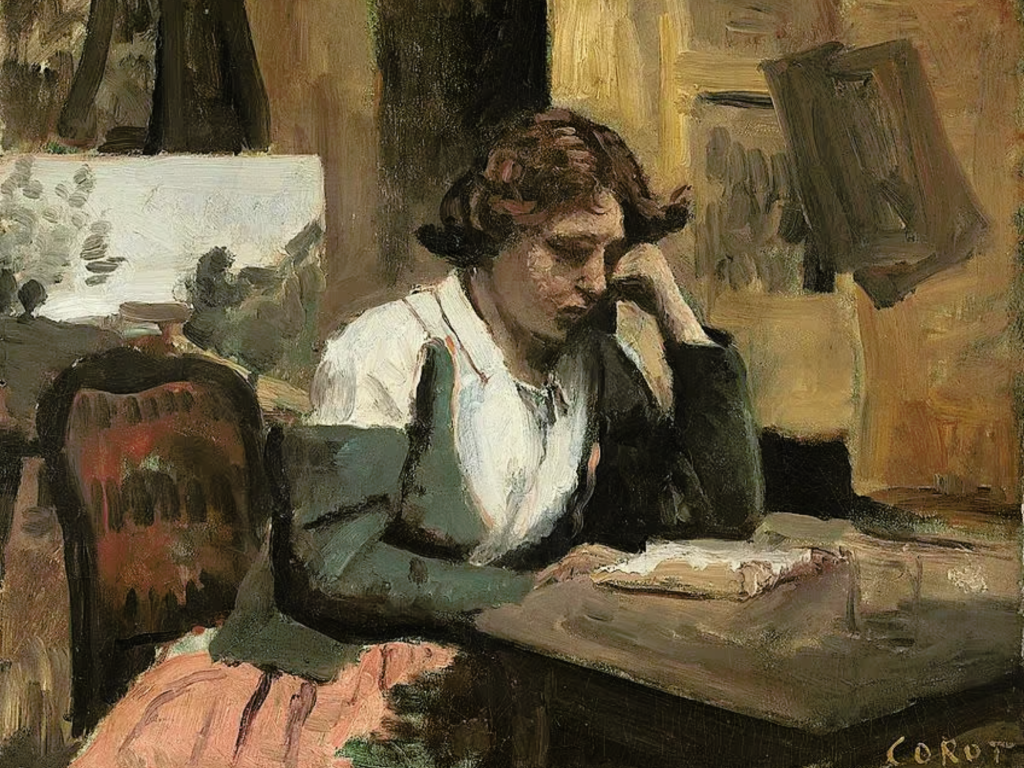

Guided by Tolstoy’s musings on what art is, I am looking closer at some scenes of 19th and 20th century literature which show characters looking at portraits of other people. In Anna Karenina Levin sympathizes with Anna, after being struck by the beauty of her portrait. In one of Poe’s gothic stories, the art of the portrait demands lifeblood. In more modern literature, two painted portraits bring women closer to an inner self-understanding. Painted art is deeply entwined with the human soul and literary art brings such intricacies to life.

what is art

People will come to understand the meaning of art only when they cease to consider that the aim of that activity is beauty, i.e. pleasure. It is necessary to consider art as one of the conditions of human life.

In his 1897 essay, What is Art, Leo Tolstoy discusses some questions which, for me, are still far from answered. The title is self-explanatory. Tolstoy searches for more or less practical things which are to help us tell good art from bad art and art from non-art at all. His ideas might seem dated for a modern audience, but the basics are still valid. How is it that we need high instances of critics and specialists to tell us, the common people, what good art is? Is art something you recognize only if you studied method, technique and history? Or should it be something simple, which anybody, even a child, can grasp?

For Tolstoy, art is pure feeling. But because the sense of beauty is selfish and self-oriented, art can’t be just something conventionally beautiful or something which just offers esthetical pleasure. It has to be something primal and deeply human, akin to emotion. Art should “infect” its beholder, like a contagious force of pure humanity. If the beholder is immediately emotionally connected with the work of art, she is also connected to other people who share the same feelings. These shared emotions raise in people a new state of being, a new consciousness about themselves and the world.

leo tolstoy, Anna Karenina (1878)

Levin stood looking at the portrait, which seemed to project itself out of the frame in the bright light, unable to tear himself away. It was not a picture, but a living, lovely woman with wavy black hair, bare shoulders and arms and a dreamy half-smile on her downy lips, triumphantly and tenderly gazing at him with eyes that troubled and confused him.

In what is now recognized to be one of the greatest novels ever written, Anna Karenina, Tolstoy busies himself, among others, also with the idea of art and painting. Levin, the rich landowner who seeks the life of a simple peasant and the solace in the beauty of nature, finds Anna’s beauty emotionally shattering. Vronsky, Anna’s lover, tries to be an artist, but his amateur painting can’t really measure up to those of a professional painter’s, who integrates religion and society in his art.

In the quoted fragment, Levin is visiting Anna at her house in Moskow, where she is living with Vronsky, secluded from society, unprotected from gossip and social judgement. Levin knows that Anna is a “fallen woman” but he forgets everything he “knows” in the moment he sees her portrait, even before meeting her in person. The powerful feelings which the portrait raises in Levin shade his preconceived ideas and, if just for a moment, make him willing to forgive and understand.

e.a. poe, The Oval Portrait (1842)

The portrait was that of a young girl. It was a mere head and shoulders, done in what is technically termed a vignette manner. The arms, the bosom and even the ends of the radiant hair, melted imperceptibly into the vague yet deep shadow which formed the background of the whole. As a thing of art nothing could be more admirable than the painting itself.

Poe’s short stories often feature an unnamed male character who tells a story which throws shadows of doubt because the character is shown to be not of sound mind or the events in the story drive the character mad. ‘The Oval Portrait’, a short story from 1842, doesn’t stray far from the formula. An unnamed character finds shelter for the night in an abandoned castle. As he wonders at the bizarre and the state of decay of the castle, he finds a remarkably life-like portrait of a young girl. A book tells the story of portrait – the model l died as the painter finished the work.

The intricate connection between life and art is taken literally in a lot of works of the gothic literature of the 19th century, and it speaks for that which most of us feel when we look at a very well executed portrait. We know we look at a representation or interpretation of life, but the image is just so real it’s uncanny. Levin had the same feeling when looking at Anna’s portrait, but Tolstoy’s novel is not gothic literature. Anna’s life-like portrait strikes a chord in Levin’s soul, while Poe’s unnamed character is horrified when he realizes the price which was paid for beauty to live forever.

sylvia townsend warner, The Listening Woman (1965)

The candlelit woman leaning from the window was no darker than she had always been. If you were acquainted with her, you could distinguish the rim of her linen cap against the hooding shadow behind, and the hand holding the candlestick. There she was. Unchanged, she was still watching from her window, unalarmed, patient and slightly amused; still, after more than half a century, waiting for Lucy Mainwaring to come into her grandfather’s library.

I previously wrote about Sylvia Townsend Warner’s later discovered short stories, and ‘The Listening Woman’ is one of them. Lucy Mainwaring is an old lady who, in an antiques shop, stumbles upon a lost painting from her childhood, which was hanging in her grandfather’s library. Memories of herself and the painting come to the surface, and, in the end, Lucy realizes that the painting has been waiting for her all this time, “listening for a step in the darkness”.

I love and fear coincidences and this story brings all that back to mind. It is by simple coincidence that Lucy steps into the antique store and finds the portrait of the candlelit woman, a piece of herself which she had forgotten and thought lost. She remembers how the portrait had accompanied her up to the age of sixteen, then it had been moved and she had lost sight of and interest in it. And now when she finds it again, it’s like she has found herself again. The portrait, with its shadows and candelit shades, has the power to bring Lucy closer to herself.

elena ferrante, Troubling Love (1992)

I had no doubt that the pastel sketches reproduced my mother’s body. I imagined that at night, when they closed the doors of their bedroom, Amalia took off her clothes, posed like the naked women in the photographs in the closet, and said: “Draw”. He took a roll of yellow paper, tore off a piece, and drew. When our father finished the Gypsy, I was sure of it and so was Amalia: the Gypsy was her.

Since Elena Ferrante is my latest obsession, I couldn’t leave her out of this carousel. Her first novel, Troubling Love, provided me with the last piece of this kaleidoscope of painted arts. The novel is a surrealist search of a daughter for her mother. When Amalia, Delia’s mother, is found drowned, Delia takes it upon herself to find out the truth behind the matter. But her search takes her down a memory lane which hides many dark corners.

When Delia tries to figure out what happened to her mother, she also tries to figure out what happened to herself. Her journey through Napoli, the city where Amalia was living and Delia was born, is a parallel to Delia’s journey through her own entangled memories of her mother and her childhood. At one point on her journey, Delia visits the apartment of her father, where she finds him painting one his eternal Gypsies – women figures which to Delia seem to have taken her mother for a model. Delia can’t separate herself from her mother and from her mother’s life story, and seeing her father’s painting again is just another push in maybe not such a right direction. Finally, Delia comes no closer to finding her mother’s killer, but she does come closer to shaping a sort of identity for herself.

We take words for granted most of the time. Beauty. Art. Memory. And these are just examples which jump to mind because of this blog post. We use words absurdly easily and we assume that we know what they mean for us, and we know what they mean for others. But when we are confronted with shockingly different points of view, which escape the landscape of our use of words, our sense of meaning cracks and we are forced to ask the big questions. What is all of this? Does it even mean anything? That’s what art does, I think. It makes you wonder. Levin, Lucy and Delia are confronted with something external to them, but which strangely brings to light something within them, something which they simply know to be true. But is it true or is it just the handiwork of the painter? That’s at least something to think about.

Leave a comment