In 1999, when Garbage released their music video for “The World Is Not Enough”, I was 13 and still a couple of years away from discovering rock and metal. You didn’t have access to music back then as you do now, and my taste in music was formed mainly by the VJs of MTV and Atomic (a Romanian music channel popular back in the day), but also by friends with access to “sources.” I remember it was New Year’s, and we were cleaning up after dinner in the living room when “The World Is Not Enough” started playing on TV. I stopped doing anything else and started watching, mesmerised. I didn’t have many chances to watch the video. Now I do, but it doesn’t have the same charm.

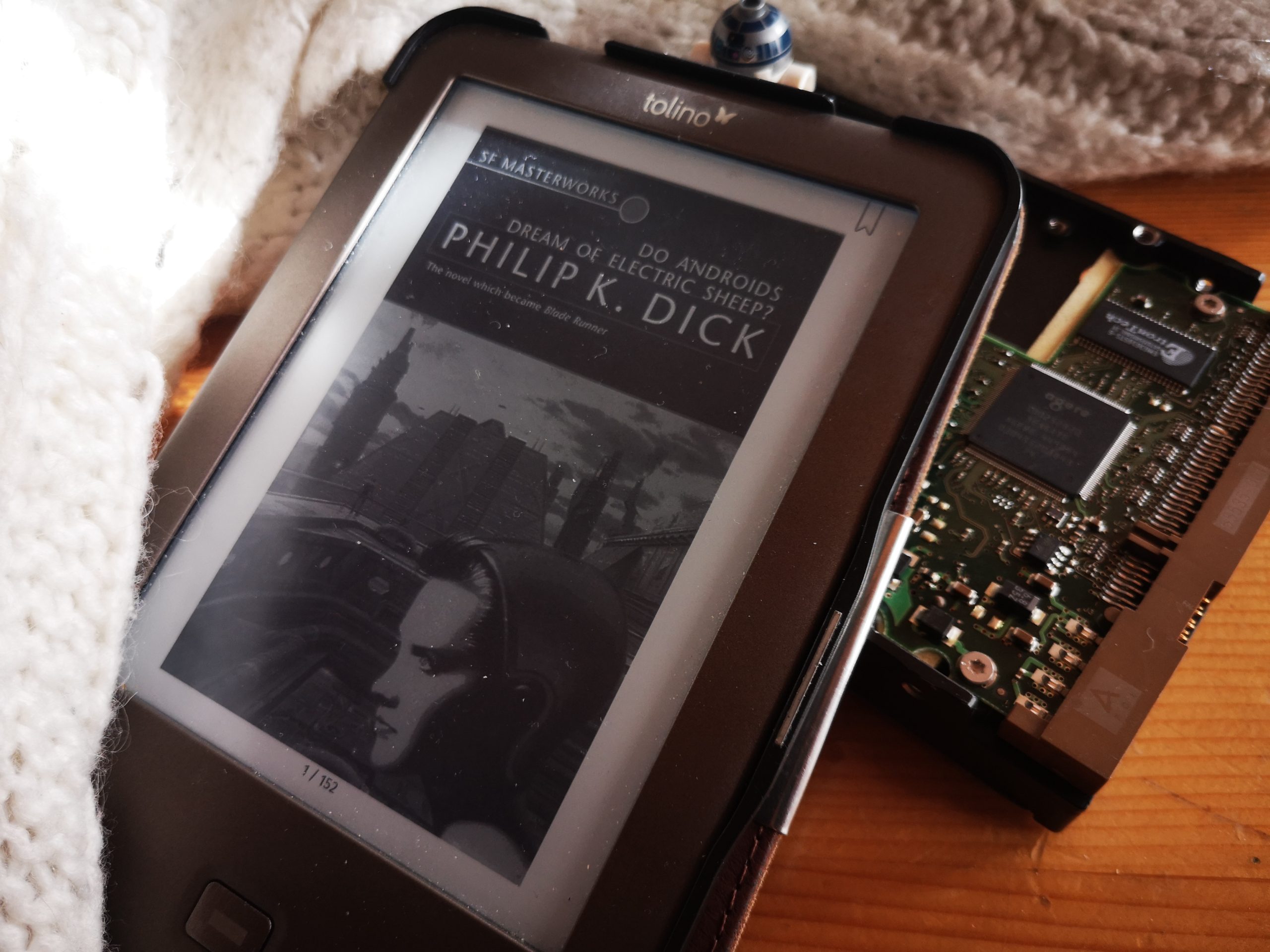

It’s the story that was so attractive to me (the song is good too, though). You are introduced to a Shirley Manson AI (lead singer of the band) as she kills the real one and takes her place before a show in Chicago. After the show, a bomb inside her body kills the entire audience. Rewatching the video now, I noticed a detail which escaped me all these years: the story is set in 1964, pretty much the golden age of robot fiction. Asimov wrote his robot stories in the 50s, and Philip K. Dick published his Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? in 1968. Robot fiction isn’t dead now, 70 years later, only that the robots/androids are rebranded as AI. This seems to me a euphemism, a way of covering up the reality of a thing and drawing attention to one of its particularities. When I think of androids as AI, their android nature moves to the background, and their intelligence takes the foreground. That is, I perceive them to be an alien breed, something supernatural possessive of life of its own, responsible for itself. I somehow forget that they are made, that each atom of their body was overseen by somebody, that each word is programmed, and each facial expression is manufactured. Fictionally speaking, of course. Humanoid androids don’t exist. AI does.

The Manson AI is a perfect replica of the lead singer, with one exception: its kiss kills. It would never be capable of showing physical tenderness because that would bring about death. It pretends to be human, maybe even wishes it were, but the human language of love betrays it. I wonder, though, what the effect would be on another android. If this act of violence was inter-species, it would, ironically, be a perfectly human behaviour. I believe this is the question mark which shadows displays of empathy in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and for which Garbage didn’t have time in a 4-minute music video. Dick’s rogue androids pretend to be human, and, in a certain sense, they are. The eight runaways stick together as a group and care about each other, but have little regard for outsiders. When Rick Deckard administers the empathy test, he looks at this emotion as a yes/no. The novel shows that there are more nuances than that.

Androids are simulations of human beings. They are not unique, as we see is the case for Pris and Rachel. So, to what extent can we say they are real? They are real in the sense that they exist in the world of the novel, for sure, but, like Pinocchio, they are painfully aware they are no real boys and girls. Deckard believes it’s the empathy they lack. Is it, though? The question gets even more complicated throughout the novel. When we meet Rachel, it is not clear if she’s human or android. When Deckard meets Luba Luft, and officer Crams brings him to the android police station, reality itself seems to have gone off the rails. The novel is plagued by misreadings, misunderstandings and confusions, deliberate or not. Isidor can’t tell a real animal from a “fake.” Repair trucks which pick up electric animals for repair are made to look as if they belong to an actual animal hospital. Emotions are controlled by an electronic “mood organ,” which can be programmed and timed to trigger emotion. Appearance is what is real, and appearance is clearly easy to manufacture. And in this world, Deckard decides whom to “retire” based on the results of a so-called empathy test. It’s ironic, and maybe that’s the author’s intention. If everything else is fake, ersatz, simulation, can there really exist something so infallible, universal and natural in all humans that a test could unmistakably pick it up?

In the world of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? only humans can engage in fusion, a simulation where people share the experience of the same feelings. This is enabled by an electronic “empathy box”, which, as we see it through the eyes of Isidor, projects the image of an elderly man climbing a hill. Whatever the man feels, his “audience” is also made to feel. Androids don’t have access to this experience because they have no empathy, it is said. There could be another explanation as to why humans keep this to themselves. As is the case with language in Asimov’s robot novels, humans need something to feel superior. In Dick’s future world, they achieve this feeling of superiority through standardized emotions which, because mediated by the empathy box, are external to themselves. Fusion doesn’t offer a real empathic connection, merely a simulation of it.

Do androids dream of electric sheep? Dick asks. The rhetoric of the title suggests a continuation: because humans do dream of living animals. Klara and the Sun tells of a world where the knowledge regarding the insides of AI was lost, and they are seen as unknown, therefore dangerous, by some. Capaldi, the engineer in the book, proposes to reverse-engineer them and make them known again. Dick’s solution is to think of them in human terms. Do androids dream of electric sheep, just as humans dream of live animals? If so, they are like us. They have emotions, strategies, desires. Even empathy and understanding for each other, be it artificial. If not, they are something else entirely. Dangerous, to be kept under control, as the authorities do on a future Earth. Whatever the answer to Dick’s question is, humans and androids live together in his, and other authors’ of android fiction, imagined societies. And we are living with AIs of our own in our very real society. And if electric sheep and toads elicit empathy in humans, as we see in the novel, maybe there’s a chance living animals elicit empathy in androids too.

your thoughts?