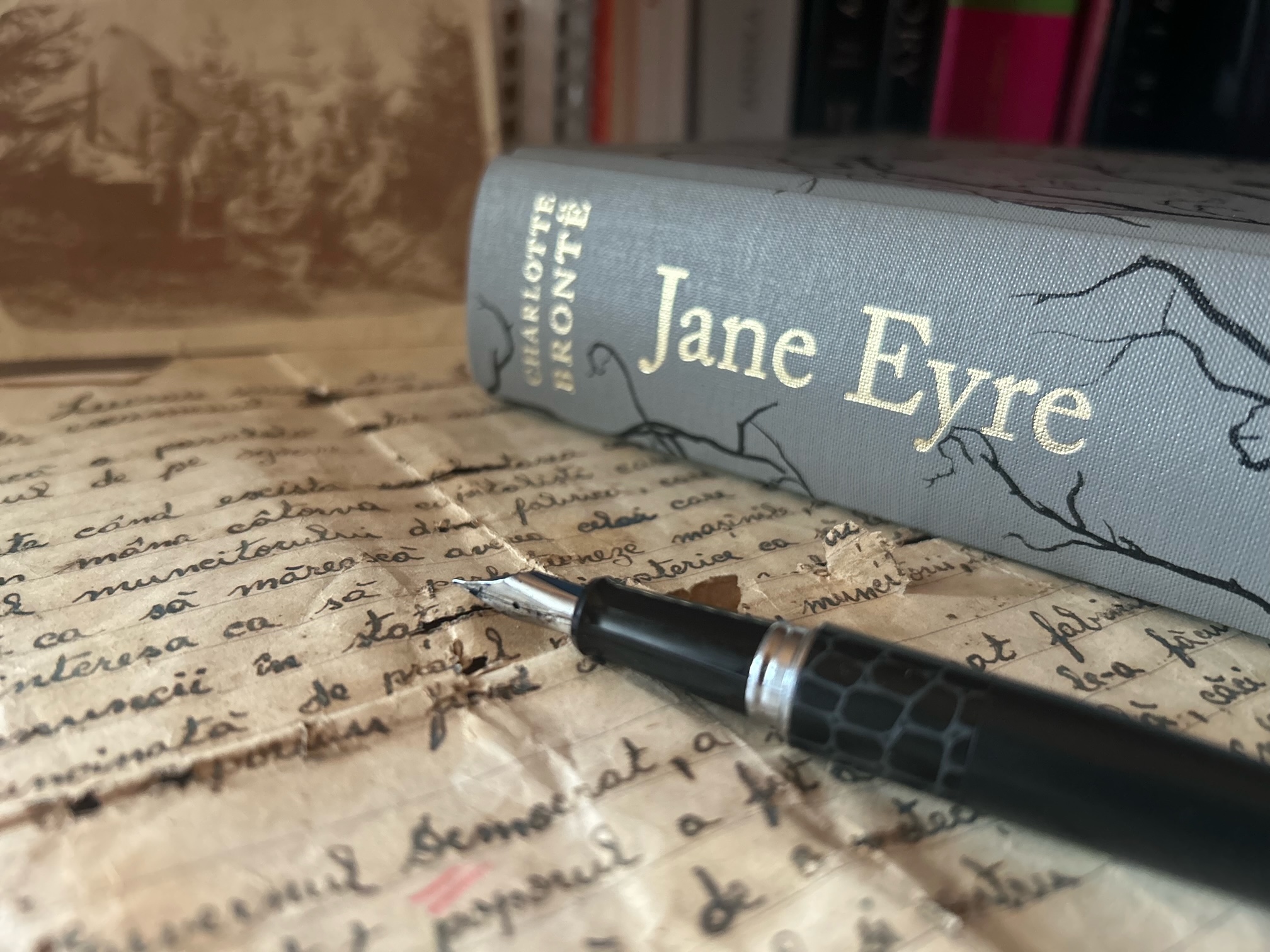

Up until this year I have never read letters of writers, I must admit. I thought I didn’t need anything more than the words on the pages of their published works. How narrow-minded I have been, I realize now! After listening to Claire Davison talk about her editing and publication of Katherine Mansfield’s letters, I decided to expand my horizons. And how much more there is to expand. Jane Eyre, both book and character, unfold in a sharper kind of light knowing Brontë’s thoughts when writing the novel and getting it published. I see now that the words on the page of a novel tell a story, all right, but the letters of its writer tell the story of the story.

charlotte brontë and currer bell in the letters

In 1831, when Brontë started attending the Roe Head school for girls, she met Ellen Nussy, who would become her best friend and her most intimate correspondent. It is assumed Charlotte sent Ellen about 500 letters, out of which about 350 have survived. Beyond the personal letter exchange with Ellen, Charlotte corresponded with a range of individuals, including publishers, fellow writers, friends, family, and even Elizabeth Gaskell, her biographer during her lifetime. For my purposes here, I have limited my reading of Brontë’s written correspondence to the years between 1846 and 1848, when she started writing Jane Eyre, had it published, and managed the responses from the public.

Oxford World’s Classics published a selection of Brontë’s letters, edited by Margaret Smith, and about twenty of them provided me with useful information about Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre and also, Jane Eyre. We know that Charlotte and her two sisters, Emily and Anne, resorted to pen names, that the novel was an instant success, that Charlotte was in awe of Thackeray and dedicated the second edition of the novel to him. And yet there’s still so much more to read from her letters.

Charlotte Brontë signed her letters either in her own name or under the name of Currer Bell, the pen name she used to publish Jane Eyre. The differences between the two personas are quite striking. Charlotte’s writing to Ellen is direct and bubbly with emotion, with facts being barely referenced. It’s like you’re listening in to a conversation between people who already know so much about eachother, that they barely need words. Currer Bell, the alter ego of Charlotte, is writing to Smith, Elder, the publisher, W.S. Williams, the reader of the publisher and close correspondent of Charlotte over later years, and G.H. Lewes, reviewer of the novel and strong-opinionated critic. Currer Bell is distant and masculine, modest and indirect in bringing his point across, yet very clear in expressing what he’s aiming at in his books. Two worlds, one person.

I read Brontë’s written correspondence as life unfolding in front of me, before being narrativized with the passing of time. “Who holds the purse will wish to be Master”, she writes to Ellen on the 9th August 1846, an idea which instantly reminded me of how Jane, even after accepting Mr. Rochester’s marriage proposal, intended to keep her independence and didn’t accept any material gifts from him. After the novel was published, on the 4th January 1848, Currer Bell writes to Williams that he should have been kinder to “the Maniac” and “I have erred in making horror too predominant”. On the 11th of March 1848 he wrote, in reference to his preface to the second edition of Jane Eyre, “I see it as a fault to bore the public with enthusiasm about a living author”. It’s reassuring to know that even sacred monsters of literature have second thoughts about their works.

Books always leave more to uncover. Subscribe to get more reflections and interpretations delivered by email.

how Jane Eyre was published

Two days ago, I celebrated the 176th anniversary of Jane Eyre by silently thanking Smith, Elder for accepting it, even though they rejected Brontë’s earlier novel, The Professor. Jane Eyre An Autobiography edited by Currer Bell was published on the 19th October 1847, a fulminating commercial success. Publishers Aylott & Jones had put their faith in Currer, Acton and Ellis Bell some months earlier, when they published Poems, but the little volume was a disaster. Only two volumes sold. The sisters offered complimentary volumes to fellow writers and, in a letter dated 16th of June 1847 to Thomas de Quincey, Currer Bell writes: “Before transferring the edition to the trunk-makers, we have decided on distributing as presents a few copies of what we cannot sell”. Just imagine the enormity of owning a trunk lined with the first edition of Poems.

Brontë started working on Jane Eyre in August 1846 and, in August 1847, she sent it to her publisher. On the 7th August 1847 Currer Bell writes to Smith, Elder of a “striking and exciting character” he was working on, for which he received a favourable response. In the letter exchange during the process of editing the novel Currer Bell wrote, on the 12th September, that “it is true and Truth has a severe charm of its own”, accepting the publisher’s suggestion to publish the book as an autobiography. On the 19th of October, the same day when the novel was published, Currer Bell received six copies of it, conveniently forwarded to him “as usual to Miss Brontë &c”. In a letter written on the same day, he expresses his trust in the “advantage which good paper, clear type and a seemly outside can supply”.

Jane Eyre, first published as an autobiography edited by Currer Bell, was an instant success. On the 28th October 1847 Currer Bell writes to Williams “I feel honoured in being approved by Mr. Thackeray”, yet he seems wary of such quick success. “I keep my expectations low respecting the ultimate success of “Jane Eyre”… A mere domestic novel will I fear seem trivial to men of large views and solid attainments”, he writes in the same letter. In November 1847 there have been insinuations in the press that the three writers Currer, Acton and Ellis Bell were one and the same person, and that Currer was a woman. Currer Bell, amused, writes to Williams on the 10th November: “your account of the various surmises respecting the identity of the brothers Bell, amused me much: were the enigma solved, it would probably be found not worth the trouble of solution”.

The second edition of the novel was published in December 1847, with a new preface. The preface replicates perfectly Brontë’s tone in her “professional” letters to the publisher and fellow writers, and it could be itself seen as a letter to the reader. Writing as Currer Bell, Brontë expresses her admiration for Thackeray and marks the clear difference between religious indoctrination and morality. “To pluck the mask from the face of the Pharisee, is not to lift an impious hand to the Crown of Thorns”.

The third edition of the novel was published in April 1848 and, at Williams’ suggestion, Currer Bell was featured as author. The debut novels of Emily and Anne Brontë had been published in November of the previous year and there had been insinuations that they were in fact written by the author of Jane Eyre. To rectify this, a note signed by Currer Bell was also added, rejecting the idea that he was the author of Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey. “My claim to the title of novelist rests on this one work alone”.

jane eyre in the letters

Jane Eyre the character is not missing in Brontë’s letters, but sometimes interpretation is needed. Reading “in” as we would call it. Who knows if Charlotte had Jane in mind when writing certain phrases, but the posterity can certainly see it as such.

A letter to Ellen on the 26th August 1846 offers insight into what Brontë wanted to do with her new character. Replying to a story Ellen wrote her, about a certain person Joe Taylor who seems to have settled on flirting with “a set of poor, unoccupied spinters”, Charlotte feels enraged at the unfairness of the situation. “I only wish I had the power to infuse into the souls of the persecuted a little of the quiet strength of pride— of the supporting consciousness of superiority (for they are superior to him because purer) of the fortifying resolve of firmness to bear the present and wait the end”. Charlotte thought it unfair that the minds of the girls were fresh and open, yet they had to entertain Joe Taylor, who had already seen a fair share of the world. The idea recurs in the novel and Jane establishes herself as the “equal” of Mr. Rochester.

Real-life experience weighs heavily in Jane Eyre, yet it seems that Brontë didn’t even use the full force of the truth. Writing as Currer Bell in a letter to Smith, Elder on the 12 September 1847, Brontë expressed great hope in a positive response from the public for the first part of her novel “for it is true”: “Had I told all the truth, I might indeed have made it far more exquisitely painful— but I deemed it advisable to soften and retrench many particulars lest the narrative should rather displease than attract.” Brontë knew perfectly well what she was aiming at by narrating Jane’s life at Lowood. It was not meant as a gratuitous shocker for the reading public, but rather as artistic criticism of institutionalized religion.

but that’s not the end

Reading the letters of Charlotte Brontë can be an endless process. The letters are not only worth reading to know her as a person, but also to learn unique details about the customs of the time. And there’s so much more to discover. In 1848 the sisters reveal their true identity, and Charlotte dines with Thackeray, who later stated he met Jane Eyre. Charlotte continues a long-time-correspondence with Williams, which can well be read as a reading diary out of which the modern reader can even pick out a couple of lost Victorian masterpieces. Those were my absolute favourite letters to read. And they can also be seen live on paper in Cambrdige! But no more time left today for me. It’s your turn now to tell me which is your favorite Brontë quirky find.

your thoughts?