I work in the testing department of a software development company and know quite something about how often mistakes, slips, flaws and any of their variations happen. Sometimes they hide in the code, sometimes in the testing procedures and sometimes in the wear which long working hours cause on the human psyche. The good news is that we have what we call rubber duck debugging for the errors in code. When in a pinch, the developer sits down with a rubber duck and explains the code line by line to it so that the duck can provide much-needed help. Suddenly, the solution to the hidden bug becomes apparent, and the duck has fulfilled its mission. The answer is already inside you, the rubber duck says to those seeking its wisdom.

I think AI creativity works similarly. Whether the AI blurts out haikus or an opinion on the entirety of written literature, this is something given to the humans to reflect on, to continue, to improve. I, like others, don’t see the result of AI creativity as an end in itself. As Stephen Marche writes in a New Yorker article, the human is the editor of the machine’s raw input. No author can go without an editor; the editor is the hidden author whose polish makes the text shine. The AI input doesn’t go unrecognised – the TLS published in 2021 a poem co-authored by AI. Sam Riviere (the editor?) is put here on the same creative level as GPT-2 (the “author”?). I doubt, though, that GPT-2 is spontaneously creative. Its artificial creativity, like its intelligence, is superficial, screen-deep. Like a DuckDuckGo search (I don’t use Google), the human asks, and the machine delivers. The human takes the first couple of search results, and life goes on. What are the names of the people who programmed GPT-2 to give Riviere the input he wanted? Who is actually giving me my DuckDuckGo search results which aid me in writing commentary like this one? One would never ask the author of a commissioned book this question. The commissioning editor commissions the book, and the writer delivers.

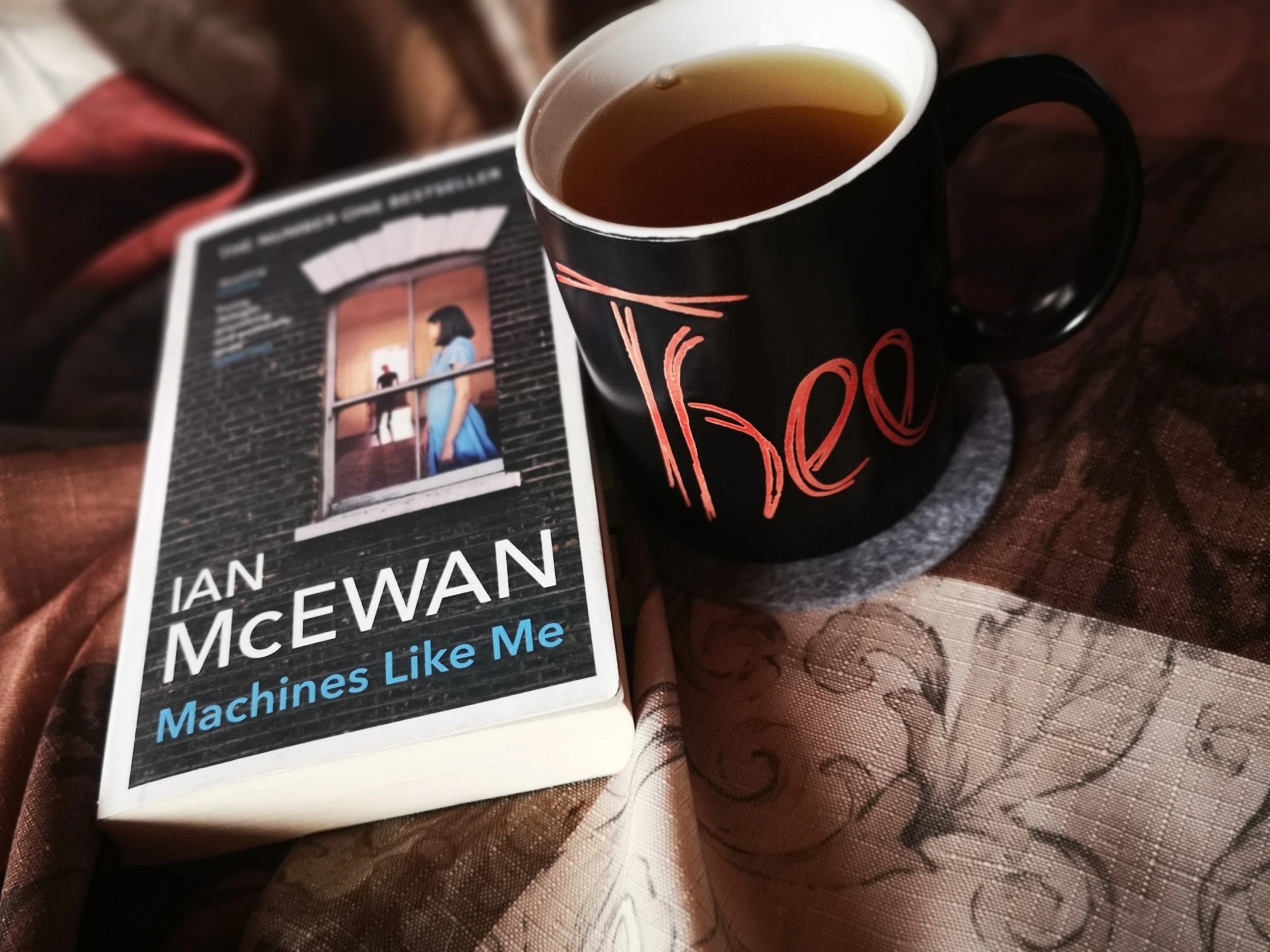

And here is the big difference between humans and AI, explored in Ian McEwan’s robot book. In Machines Like Me, Charlie, the human owner of Adam, the AI, doesn’t quite grasp, and sometimes even nullifies Adam’s perceptions, pretty much what I did with the AI-written part of the co-authored poem in a previous paragraph. Charlie tries to picture how Adam sees: “an image on some internal screen that no one was watching”. He explains Adam’s reaction to his being turned off as “some designer’s notion of how consciousness might manifest itself in movement”. When Adam confesses his love for Miranda, Charlie refuses to acknowledge it: “There must be a problem with your processing units”. Charlie understands Adam’s human-like reactions as metaphors, which “mean” something else for Adam than they do for him. He doesn’t grant Adam the rights a sentient being might have. Well, either that or Charlie must admit that Adam does a better job of being human than Charlie does.

There are as many ways of being human as there are humans on the planet, and for me, this means doing your best when it comes to empathy, lending out a helping hand, inner reflection, love. These sound very nice and clean in a vacuum, maybe, but their edges blur when thrown into the messy muddle and routine of day-to-day existence. They stop being clear-cut puzzle pieces of a perfect self and turn into contradictions. That’s where human limits reveal themselves, and AI shows that it has no limits. Adam donates his stock market gains and pursues justice to the letter when he turns Miranda in for her act of unlawful revenge. Virtue gone nuts, in Miranda’s words. It’s what maybe the ideal citizen would do in a communist utopia, but what about real, breathing person?

Adam has high hopes for a utopian future world, where “the marriage of men and women to machines is complete and literature will be redundant because we’ll understand each other too well”. In his view, literature exists in order to work through our failures, dreams of violence, and incapacity to communicate with each other. Be that as it may, I shudder to think of a world without literature, misunderstandings, failures. Adam would see a future fashioned in his own liking, but to me, that seems like an up-to-date version of Oceania and Nineteen Eighty-Four. Utopia for AI is a dystopia for humans and, as we see in Machines Like Me, the other way around.

Other AIs, especially females, can’t cope with the discontinuities and contradictions of the human world. From a fictional Alan Turing, we hear that several of them terminate themselves willingly, one way or the other. This illogical human world was unfit for their logical nature. They either arrived too early, and this world was not yet prepared for their inhuman logic, or the world is a given, and they will need to adapt. That is, tragically, be more human. Their termination means they see something we don’t see anymore. They see solvable problems which we just got used to. They look where we turn our heads. They came from the outside in our world, which we only know from the inside, and decided, unlike AI in more conventional sci-fi literature, they have nothing to teach us, and we are not even fit for an overtake. We survive because we bend and we hide. They couldn’t.

Like the rubber duck developers use to debug their code, McEwan’s AI book doesn’t really say anything about AI. We, readers, come to the book with questions about our future, AI’s future, differences and resemblances between us and AI, and AI creativity in literature and the arts. After some hours of reading, imaginary dialogue and introspection, we go away with a shifted mindset and a skewed perspective upon nothing else but our very own selves. Did we debug the code which keeps us functioning in the world? Maybe we would, if little by little, we stop being immune to it and act as if we actually were alive.

your thoughts?