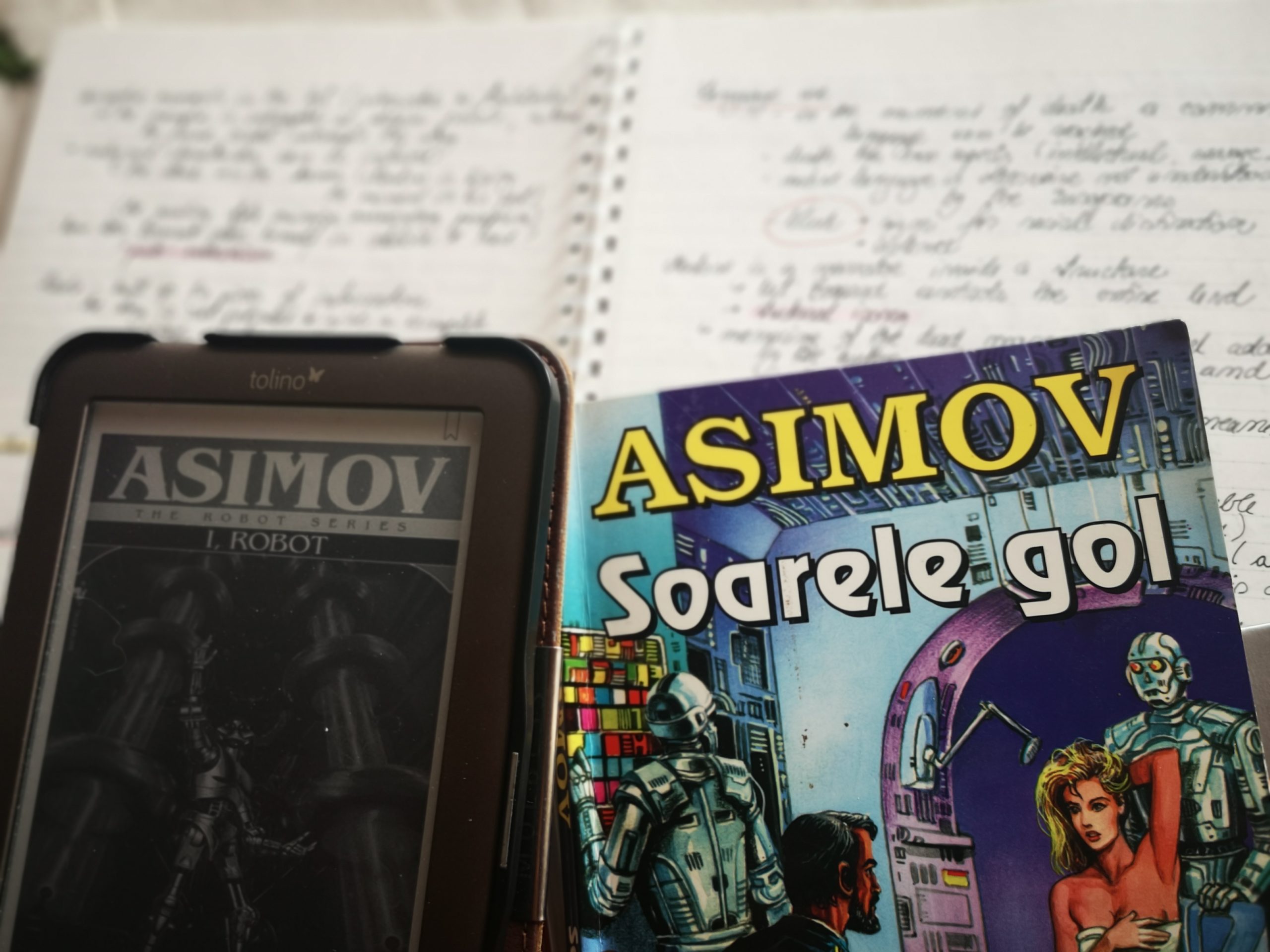

Because I work in an automotive company, I get quite close to a variant of talking robots every day of the week. Automotive means that we do something which has to do with cars one way or another. The specific company I work for has been involved for more than a decade in creating the infotainment systems which any owner of an Audi uses daily. Whenever they listen to their favourite radio station or start the route guidance to the closest Italian restaurant, they interact with a version my colleagues and I have spent years developing and testing. To call our infotainment system A.I. would probably be stretching the definition a bit, but the robots in Isaac Asimov’s story collection I, Robot and his novel The Naked Sun do have some things in common with our infotainment system. They evolve, they speak, and they refer to themselves as “I”.

First, they evolve. In I, Robot the robopsychologist Susan Calvin tells stories of how robots evolved from having a basic system of morals to speaking and finally turning into de facto leaders of humanity. In ‘Robbie’, the first story of the volume, Calvin tells of the emotional connection between an 8-year-old girl and her robot “nursemaid”. Robbie’s job was to play with the girl and keep her company. He could interact with her, listen to her reading ‘Cinderella’ out loud, but his metal throat hadn’t been taught to form words. Thinking back to the time ten years ago, I find the simplicity of those old infotainment systems quite striking. You had a rotating button to input a destination letter by letter, without having it sent to some online server and reloaded for the same driver in another car. You could play some local FM radio stations and weren’t sitting frozen in front of the scrolling thousands of online radio stations, not knowing which one to choose. And most importantly, the system wasn’t listening back then.

Second, they speak. Or, to be accurate, they were programmed to form words. It’s strange using human-specific words for machines you know were programmed to mimic what humans organically learn. In ‘Catch That Rabbit,’ Powell says, “Human disorders apply to robots only as romantic analogies,” but his remark could be extended to everything which is fundamentally human. And we cling so desperately to the notion that humans are the only mammals that can speak. Yet we are willing to give this property (because it does become a property in a mechanical context) to that which we are building.

In the past years our infotainment systems have developed natural speech recognition and have reached a level where you can almost have a natural conversation with it. (Her?) “Hey Audi, what’s the weather like today?” I ask out of the blue, during a test session, where I have to check whether the latest build has all the fixes included. The system is always listening, but sometimes that long-awaited fix hasn’t been included. If this happens, I repeat the command. The system is still listening. “Hey Audi, what’s the weather like today?” Nothing. “Hey Audi, what’s the weather like today?” while this time my voice lowers, menacingly bored, accentuating different words, almost barking the command at the very much un-sentient and un-caring screen. They definitely haven’t included that fix.

After giving language to their machines, humans assert their superiority by reaching out to the inbuilt emotions of language, which machines have no access to. In Asimov’s stories, robots refer to humans as “masters.” Humans refer to robots as “boy”, more commonly, but also “junk heaps” and “metal mess,” if they are really upset. I refer to my testbench as “Audi,” but that doesn’t mean that when I lose my patience, I don’t call it millions of different ways in my head. And this has absolutely nothing to do with the hours of work other colleagues put into bringing the system to the level that it can talk to me. It has to do with me knowing that I am interacting with a system that can answer me and yet doesn’t. I project my emotions and the stress of the day (my hunger perhaps if it’s almost lunchtime) to a heap of code and hardware the inner workings of which I can’t even begin to understand.

Third, they refer to themselves as “I,” and this is where we step into the territory of undeniable discomfort. “Hey Audi, I’m hungry”, I confess to my testbench in yet another test session. This time the fix is included, and “she” answers back with a list of restaurants. “I found some restaurants along the route”. This type of answer never fails to take me aback a bit. “I”? Is that “I” meant to include the group of developers who worked on this response? Or is that “I” the projected ghost of a very unrealistic but helpful person, who in some impossible world would give you this response if you walked up to them on the street? The robots in Asimov’s world are built based on the three laws of robotics, a rudimentary system of morals meant to ensure that robots put the life of human beings above any orders they receive and above their own existence. Things are, of course, never that simple, and the stories in I, Robot, and the murder in The Naked Sun, stand proof of that. If one does wish for a dose of naïve simplicity Dr Lanning in ‘Evidence’ provides it: “you just can’t differentiate between a robot and the very best of humans.” My Audi is willing to provide lunch options when asked rather insolently. Apart from my husband (maybe), which human would?

In a 2021 article in The New Yorker, Stephen Marche argues that human language is littered with biases and dark abysses, which can’t help but be transferred to the machines this language is being taught. Considering this argument, one wonders how ideal this very best human-robot can be if it can’t get above the nitty-gritty of speech. In The Naked Sun, detective Bayley dissects the language of his robot-partner, R. Daneel Olivaw, observing that a remark of his can be perceived differently, depending on whether one knows that his partner is a robot or not. In the first case, Olivaw simply doesn’t want to “give offence to any human”, while in the second, his response “sounded like a series of subtly courteous threats.” The robot’s speech can’t be taken at face value. It must be put into the broad context of technological evolution, science and, most of all, humanity of science. It can’t even be called “language,” in my opinion, because it lacks social and emotional context. I want to call it “I-Speak” because the robot is an “I” that “speaks,” while none of these words is value-free. Maybe this way, I can step back from my low, menacing tone of voice next time I ask my Audi what the weather is like on any given day.

I read The Naked Sun in its Romanian translation – Soarele gol

The Audi features I refer to in this blog post (PSO2.0, online and satellite radio, natural speech recognition) are detailed below. Except for “Hey, Audi” all speech inputs and answers are examples meant to serve the point regarding human interaction with robot language and may or may not occur in real cars.

https://www.media.audiusa.com/en-us/releases/479

your thoughts?