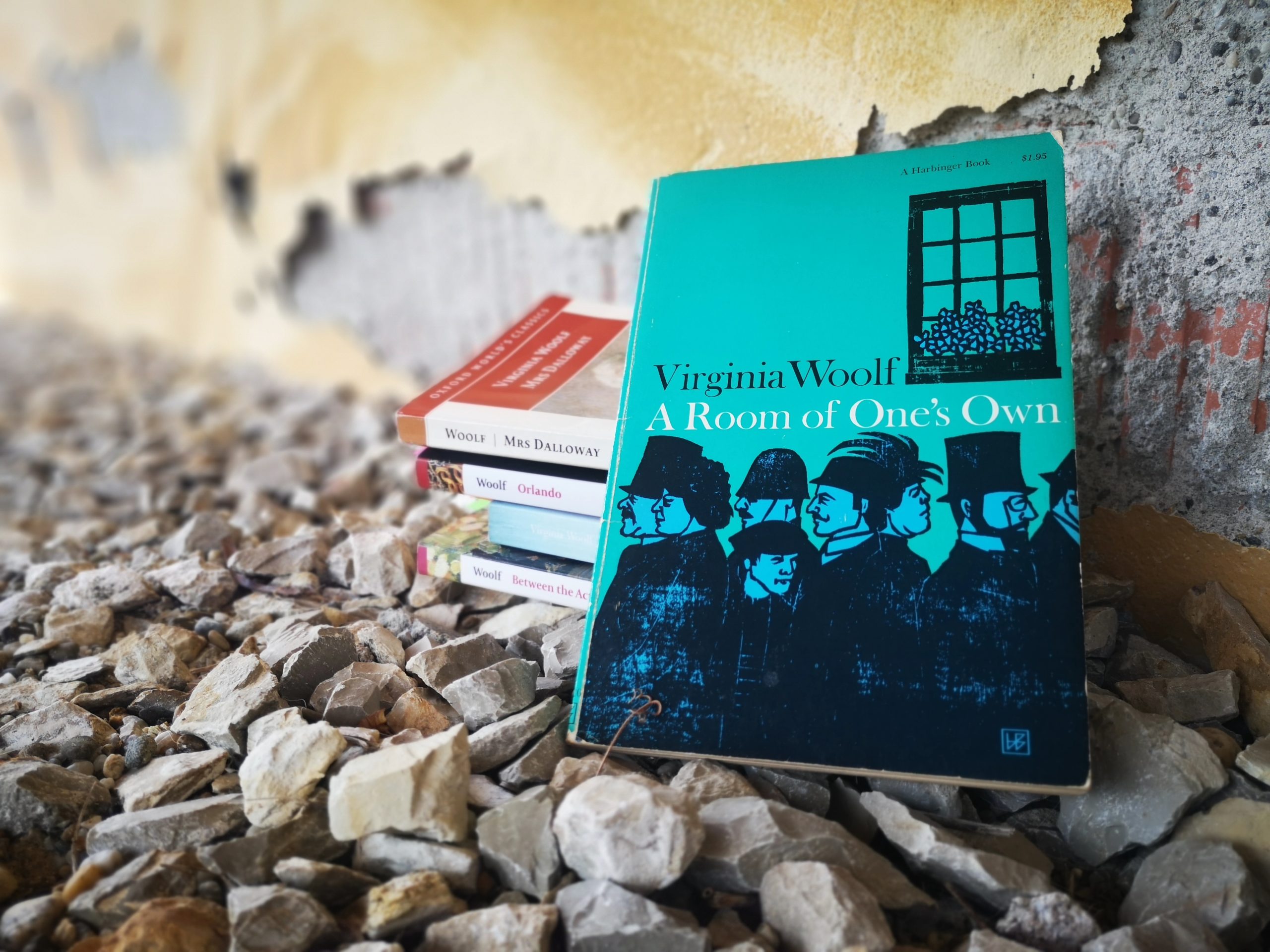

In ‘The Modern Essay’, originally published in 1922 in The Times Literary Supplement, Virginia Woolf expresses her admiration for the essayists who root facts in the soil of fictional writing. This is a model she would take over in what is today seen as an early manifesto of feminism: her 1929 essay, ‘A Room of One’s Own’. The text is a rework of two lectures which Woolf delivered at two women’s colleges in 1928 and it essentially drafts a literary history of women’s writing, while offering an “opinion upon one minor point – a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction”. I say “essentially” because, of course, as it is with all of Woolf’s works, this essay is so much more.

The text is, at its core, a narrative thread following Mary Beton, whose story Woolf repurposes as an essay by framing it between a few introductory paragraphs and a conclusion. The introduction sets the stage for the story which is to unfold: “the story of the two days which preceded my coming here”. The conclusion is baffling: “two criticisms, so obvious that you can hardly fail to make them”. In other words, Woolf puts us to the test. Have we been following the thread of her two days and have we sensed where the footing of her argument was shaky? She was never about to give us any “nugget of truth”, quite the contrary. The two points of self-criticism enrich and encourage our own critical thinking.

It is difficult to make the distinction between what is narrative (Mary Beton’s train of thought) and what is factual argument (the reason why there is no tradition of female writing). Mary Beton’s “story” is told in real time, as she goes about her day, visits the British Museum, has lunch and browses books on her shelves. The story also features two other Marys. Mary Seton is the narrator’s friend, assumingly a tutor at a women’s college. Mary Carmichael, contemporary of Mary Beton, is a writer whose novel the narrator believes to be a milestone in the tradition of women’s writing. The three Marys are fictional characters, but they also serve to make the points which are part of the essay’s argumentative structure. Looking at ‘A Room of One’s Own’ both as fiction and nonfiction, the reader can transcend the simple fiction/nonfiction separation and appreciate it as its own form of rhetoric.

In the paragraphs of narrative fiction, Woolf’s style projects the reader straight into the mind of character. For instance, while browsing through a newspaper found in a restaurant, the narrator refines her theory of how “women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size”. As we follow Mary Beton and hear her thoughts, the theory of why there is no tradition of women’s writing unfolds before our eyes. The criticism Woolf offers in the conclusion is also part of the rhetoric of her factual argument. A fallible, humane, character is more likely to get under the reader’s skin, and her opinions more likely to reach the reader.

Mary Beton meets Mary Seton after a visit to Oxbridge and Fernham, two invented men’s respectively, women’s colleges. In the evening, the two friends muse over theories as to why lunch at Oxbridge was much more luxurious than dinner at Fernham. Sweeping five hundred years of history in a couple of pages, Mary Beton finds an explanation in two scenes in her head: “masons on a high roof five centuries ago” and “lean cows and a muddy market and withered greens”. The two scenes describe the two colleges she had visited and form the background of her theory and the condition of the woman writer in history: “if only Mrs. Seton and her mother and her mother before her had learnt the great art of making money… we might have been exploring or writing or going at ten to an office and coming home comfortably at half-past four to write a little poetry”. As Mary Beton (and Woolf herself) sees it, women before the 19th century didn’t have the material conditions to support their writing.

Back in her room after the visit to the colleges and to the British Museum, Mary Beton browses some books on her shelves. One of the books is by the contemporary author Mary Carmichael. From Mary Beton’s perspective, Mary Carmichael could be the woman author entrusted with recording and exploring obscure lives, carrying forward the tradition initiated by an imaginary Judith Shakespeare. By giving obscure, unknown women a fictional life, Mary Carmichael would serve as a milestone in a parallel, feminine, space of ideal fiction where women’s writing would be developed for the next “hundred years’ time”. In this way, Woolf the essayist briefly looks into a future of writing, an act which closes an entire narrative course which could well be described as utopian.

As discussed by Melvyn Bragg and his guests in an episode of In Our Time, the three fictional Marys are based on three Marys from a 16th-century ballad. They are left behind, in mourning, when their companion Mary Hamilton is executed for adultery and murder. Drawing on the ballad, Woolf emphasizes unity and a shared sense of purpose among women writers and forms a metaphorical basis for her essay. The three Marys of ‘A Room of One’s Own’ could be seen as the cornerstones of tracing, uncovering and creating a women’s literary history, the single voices of a large community. Woolf’s call to women writers is to stand together in a community of creativity and writing, and bring “the experience of the mass is behind the single voice”. We are still waiting for Judith Shakespeare to arise, says Woolf, but for that we must write.

I wrote this post in preparation for the Literature Cambridge 2023 Virginia Woolf summer school. The series of lectures and seminars looks at some of the women characters in five of Woolf’s works.

your thoughts?