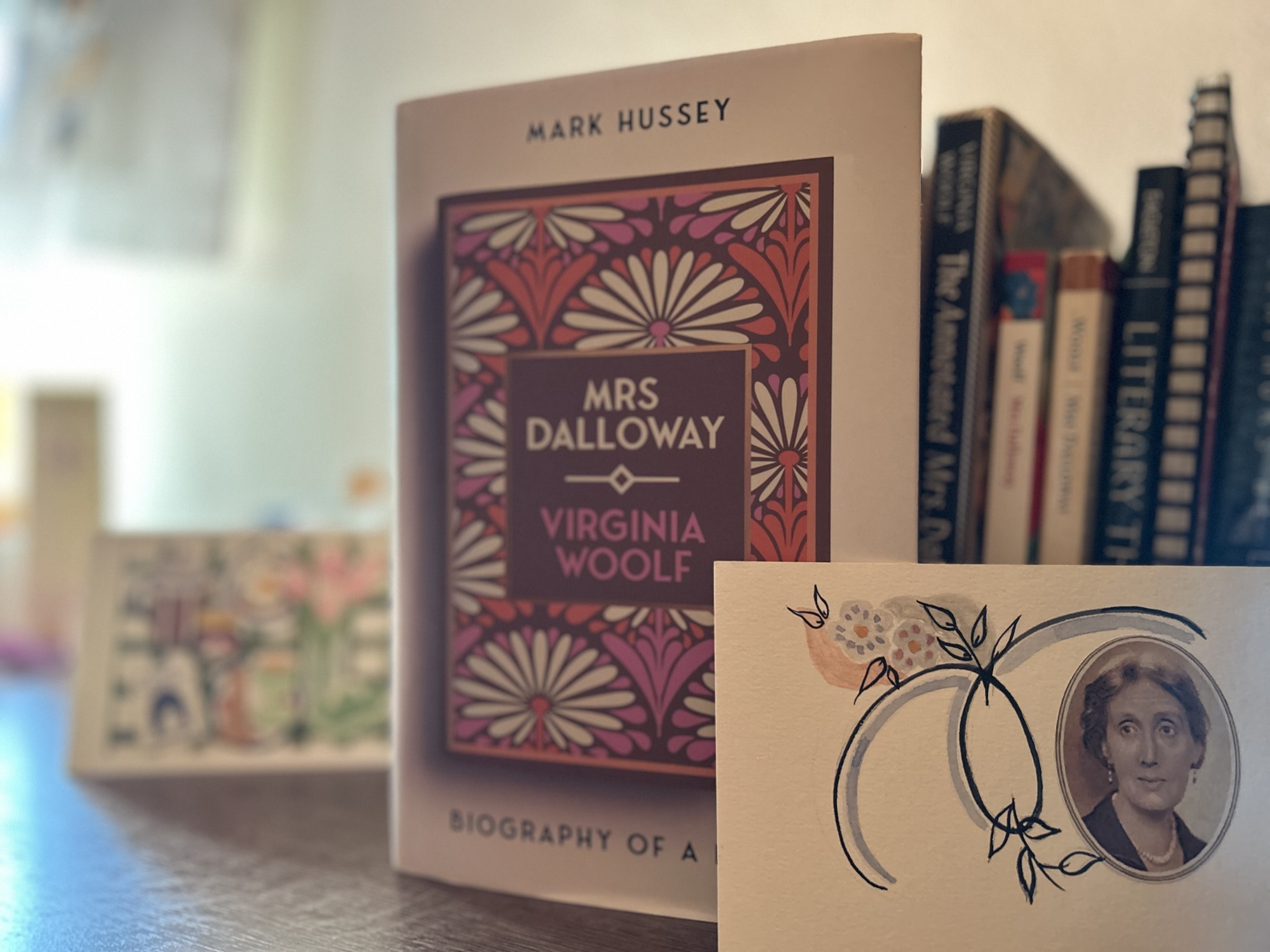

Mrs Dalloway: The Biography of a Novel by Mark Hussey was published on the 14th of May 2025, precisely 100 years after Virginia Woolf published her very own Mrs Dalloway. I’ve read Woolf’s novel so many times now, I really had the feeling I know everything there is to be known of it, yet Hussey’s book proved me so wrong. I loved it! Even for a reader like me, or maybe especially for a reader like me, who likes to look at a novel from different angles and different points of view, there is so much still to be discovered about Mrs Dalloway. And Mark Hussey does a great job at helping along the way. He tells the story of how Virginia Woolf wrote her now world-famous story of a middle-aged socialite who goes out in London one June morning to buy flowers for her party herself. Her life mirrors and parallels the life of Septimus Warner Smith, a shell-shocked soldier returned from the Great War, but for whom the war is far from over. Hussey’s story stretches the life of the book to cover character creation, critical reading, Woolf’s sources of inspiration, initial reception of the book and its afterlives.

what is Mrs Dalloway: Biography of a Novel?

This is a book for the readers who want more. Hussey assumes familiarity with the plot, so it’s certainly recommended to have read Mrs Dalloway before getting on with its biography. The book offers the obvious information a common reader might look for in such a biography: diary excerpts telling the story of how Woolf drafted and then wrote the book, variations of Mrs Dalloway starting with the early days of The Voyage Out, potential alternative endings Woolf had in mind, critical receptions of the contemporary readers. But beyond the information he presents in the book, what Hussey achieves particularly well is summoning the feeling of an exceptional author and human being writing a book which for her meant to put into practice an entire philosophy of fiction and creation of character. Straight at the beginning of the book the author offers a sense of the writer Virginia Woolf:

Virginia Woolf was a messy writer. Her surviving drafts are often stained by cigarette ash or a dog’s pawprints. The large wooden tables she preferred in her writing rooms were covered with manuscripts, bottles of ink, overflowing ashtrays and the notebooks she made for herself

As a lover of Woolf, you can’t not fall in love with a book which starts like that and which acknowledges her personality. And the author himself is a distinguished scholar of Woolf, but, more than that, a devoted reader: “My collection of editions of Mrs Dalloway has swollen past any reasonable number”, he writes, leaving the common fiction reader wondering how much it would take to reach the same achievement. But such moments pass quickly. Mrs Dalloway is 100 years old in 2025, and the book sets out to explore how and why we are still reading it today.

interpretative threads

Woolf was not only a writer of fiction but also a professional essayist and reviewer, to say nothing of being a publisher. She conceived of Mrs Dalloway and The Common Reader as ‘two books running side by side’, and was also publishing other essays and reviews the whole time she worked on them.

One of the great revelations I’ve had while reading the book was the idea that Woolf meant The Common Reader and Mrs Dalloway to be read together. Both were published in 1925, and, while some of the essays published in The Common Reader had been published before, some essays were especially written for her “reading” collection, as Woolf conceived of the volume. Essentially, the essays indicate a how-to for reading and understanding Mrs Dalloway, while the novel is the physical shape of years of studying great novelists and thinking of how fiction should be written and understood.

Reading ‘On Not Knowing Greek’ into Mrs Dalloway, Hussey gives the particularly striking example of the design of Mrs Dalloway and how it resembles a Greet tragedy. In the essay, Woolf writes that the ancient Greek tragedies included the chorus to express the poetry of life without interrupting the whole felling of the play. In Mrs Dalloway, Hussey suggests, such a ‘choric’ element is the moment when Peter falls asleep on a bench in Regent’s Park and dreams of an ancient figure who is both part and not part of human life. I, personally, am convinced by this interpretation because Peter’s dream is very baffling otherwise. It is part of the feeling of the novel, and yet so foreign and difficult to place.

But Mrs Dalloway is not only abstract feeling. It is a very concrete novel with very concrete characters who spend their day in a very concrete London. Woolf expresses this concreteness at the design level by a method of creating character which she called her “tunnelling method”. Characters are seen from different angles: from the outside, but also as they reminisce on the past and bring it back to life. Their lives, Hussey writes, are “filled in gradually as we come to know them in the course of the day”, and this translates into a “tunnel” which Woolf writes for each character. As we hear Clarissa’s mind echoing the chimes of Big Ben and we witness Septimus’s mind melting in the trees of Regent’s Park, we are violently pushed into their tunnels – private spaces beneath the surface of ordinary life.

the literary background of Mrs Dalloway

In her essays published in the early 1920s Woolf is preoccupied with a new way of writing character in fiction. As Hussey writes, “with ‘Modern Novels’, Woolf was joining a debate about the nature of character in fiction that occupied many writers throughout the 1920s”. In Jacob’s Room, published in 1922, this preoccupation takes concrete experimental form: Woolf abandons conventional biography, and sketches Jacob through fragments of other people’s impressions and the spaces he inhabits. The result is a deliberate absence at the novel’s centre, a critique of how novels traditionally encapsulate character. In August 1924 Woolf publishes ‘Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown’, an essay critiquing the “traditional” method of writing character. One year later, as Mrs Dalloway was published, she found her “tunnels”, a culmination of the questions she had been working through over the past years.

The book was published on the 14th of May 1925, simultaneously in England and in the US, and the public opinions were, as usually, mixed. What Woolf was doing, was give the reading public, and the reviewers, a new kind of novel, something they were not accustomed to. They were used to being given answers, descriptions and conclusions, but Woolf was giving them only more questions, a challenge for them to find, if possible, a Mrs Dalloway and a Septimus for themselves. Some critics admired Woolf’s skill in capturing the texture of consciousness: “the ebb and flow the imagery. the rhythm of the sentences, follow the course of the emotion” writes reviewer Edwin Muir. Others found the absence of a conventional plot frustrating: “on the one had, beautiful writing; on the other, not much of any interest seemed to happen”, writes Hussey of the flatter reviews. As I understand it, there was clearly an awareness that Mrs Dalloway was not a minor experiment but a deliberate reimagining of what the novel could do.

afterlives of Mrs Dalloway

In the 100 years since its publication, the novel has been adapted for stage, radio, and even dance, each medium exploring its fluid sense of time and inner life. Scholars continue to mine its portrayal of mental illness, urban modernity, and women’s interior worlds, readers find in Clarissa’s London walk and Septimus’s anguish reflections of their own lives, and classrooms of students read and appreciate Woolf’s literary skill.

Today, in 2025, readers request an official Dalloway Day to properly celebrate their beloved author and her book. Artists draw inspiration on the novel and create art works which celebrate its beauty and its presence in our contemporary lives of the soul. And If you want even more than the more offered by Mrs Dalloway: The Biography of a Novel by Mark Hussey, I recommend listening to The Virginia Woolf Podcast. This is a show hosted by Karina Jakubowicz who interviews guests whose work and career have been influenced by Virginia Woolf. The interview with Mark Hussey himself and the discussion on Mrs Dalloway’s Party are particularly interesting.

your thoughts?