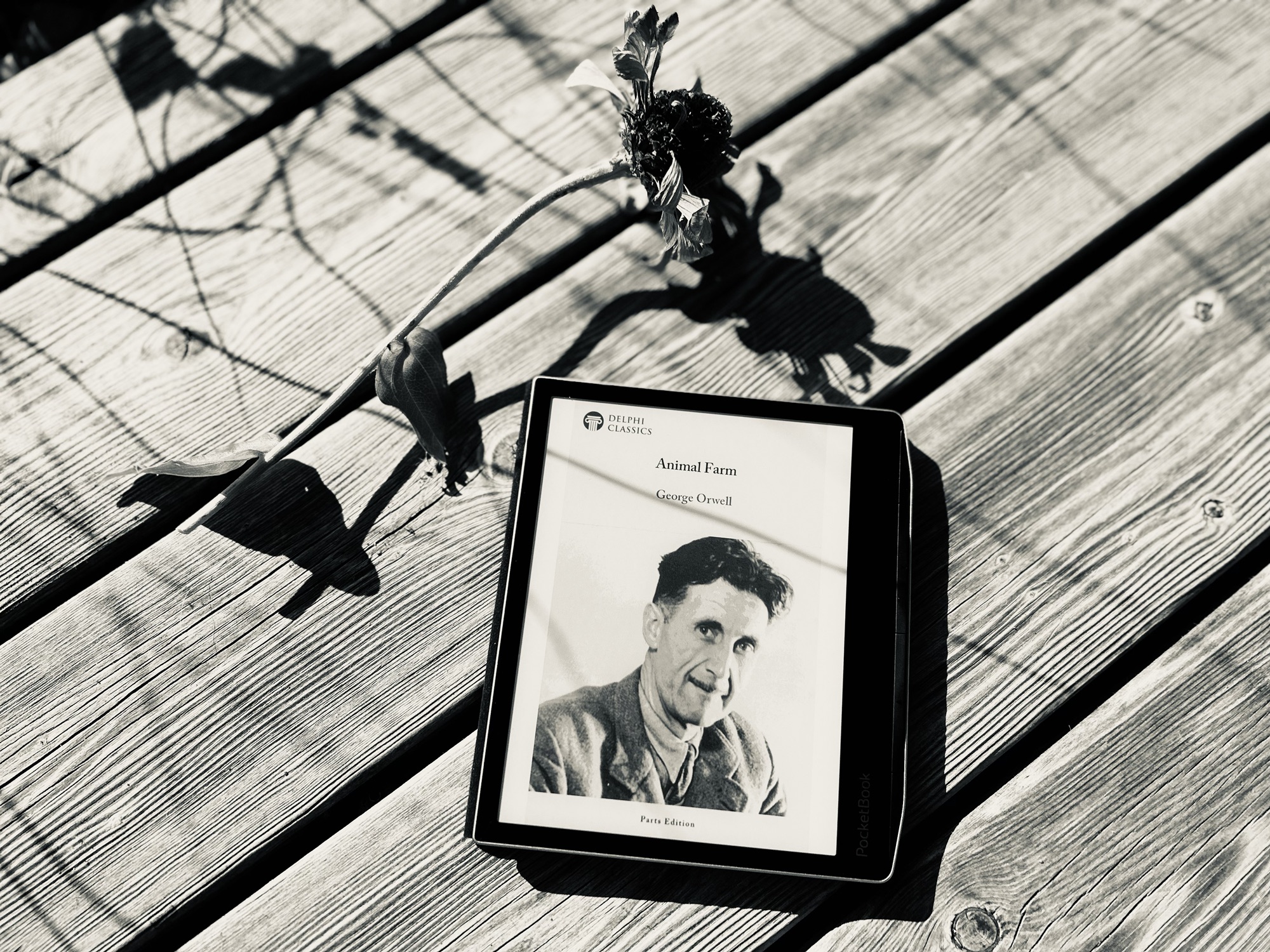

Thanks to my wonderful book club at work, a world-shattering book landed again in my hands. This happened last time in spring with Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend, the reading of which led to a couple sleepless nights and an ever-thicker TBR pile. This time, we read George Orwell’s Animal Farm, published in 1945. I read this one some years after Nineteen Eighty-Four and it convinced me yet again of the fragility of human nature and how alone we are in the world, even if, or especially if, we live in a society led by a government that advertises caring for its people. The book club discussions raised questions such as why it’s so difficult, even impossible, to create a just society in the wake of a totalitarian one and what is Animal Farm actually doing. Is it a how-to on starting a dictatorship or a warning against trusting your leaders? Like with all great books, we all agreed, there are no easy answers.

the story of an ideal gone wrong

By now everyone knows at least something about Animal Farm. That the animals on a farm rise against their human oppressor and start their own democratic regime. That the pigs are the smart ones who take on leadership. That the two leader pigs are allegorical figures for the two main figures of the 1917 Russian Revolution Stalin and Trotsky. And finally, maybe even that the ideals of the revolution which the animals started don’t quite hold up in the new regime which, over the years, starts looking more and more like a dictatorship.

So I didn’t go into the book completely blank. Yet the feeling of reading it was somewhat different than what I had come to expect. The most striking aspect for me was how the initially democratic regime led by the two pigs Napoleon and Snowball descends more and more into totalitarianism. The first days, even the first year, was full of happiness that Jones, the human oppressor, is gone. And yet with time, this remains the only thing which the new “government” relies on to keep the animals obedient.

The animals establish the seven commandments of Animalism, the law set into place to make sure that all animals will live free and prosper. Yet with time each single one of the laws is corrupted, as the pigs turn more and more into that which all other animals despise: humans. The chilling “All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others” shows its teeth shortly after the rebellion, when it is decided that all milk and apples are to go to the pigs. “It is for YOUR sake that we drink that milk and eat those apples” Squealer tells them, the pig who convinces everybody that anything the pigs do is done for the sake of the animals. The ultimate argument which drives the final nail in the coffin of any timid criticism is the neverfailing “sure there is no one among you who wants to see Jones come back?”

a world of story

What Napoleon’s regime heavily relies on is Squealer’s tireless storymaking. His stories are an art of adaptation. When food rations are cut, he spins the shortage as a heroic sacrifice for the greater good. When Napoleon makes deals with humans – theoretically considered enemies – Squealer reframes these betrayals as strategic alliances. Which, of course, they are. Strategic for the pigs, that is, with little benefit for the daily life of the working animals. But such details Squaler doesn’t see fit to mention.

Orwell writes, “The others said of Squealer that he could turn black into white”. His constant manipulation of language and historical narrative ensures that no matter how oppressive Napoleon’s actions become, the animals remain convinced of the good intentions of the ruler. They lack historical memory and the intellectual capacity of criticizing the regime and accept whatever revisions of reality Squealer throws their way. “The animals were conscious of a vague uneasiness. They remembered passing such resolutions: or at least they thought that they remembered it”

how animal farm strikes the reader

Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four are pretty similar from thematical point of view. They are both about life in a totalitarian society. Yet the big difference between the two of them is that the first one features animals as characters and the second one deals with plain humans. The fact that Orwell turns to animals echoes of course the fables of Aesop and fairy tales. These works take familiar situations and characters and turn them around, forcing the reader to look at things from an unfamiliar perspective. Orwell transparently forces us to reconsider the dynamics of power, control and corruption without the immediate baggage of real-world politics.

It is of course easy to make associations. Napoleon “is” Stalin. Boxer, the horse who works himself to exhaustion “is” the working class. Mollie, the young horse who lives in nostalgia for Jones “is” the higher class who longs for the old regime. But Orwell does more than create these one-to-one representations. He layers the story with broad questions of who holds the power, what is truth and how it happens that history repeats itself. The novel sheds light not only on failures of communism, national-socialism or what-have-you. What it does is to reveal the mechanisms through which tyranny takes root in any society, especially one which comfortably regards itself as democratic and “better”.

There were some slight disagreements in our book club discussions. Can we blame Boxer or Benjamin for not speaking up against the harsher and harsher actions of Napoleon? Is language a tool for manipulation or the basic brick you need lay down the foundation of democracy? We realized there are no black and white answers, of course. But what we all agreed on was that Animal Farm remains as relevant nowadays as it was 80 years ago. Orwell recreated a dictatorship using stick figures, but splinters of those sticks, maybe even logs, can still be recognized in political regimes all over the world.

your thoughts?