Women and flowers. Flowers and women. They come together so naturally. In April you see young mothers carefully watering the geraniums which have maybe survived winter in a cold basement flooded with light. Lily of the valley comes back relentlessly every year in a garden with only an old woman left to look after. And lilacs shot up in the sky in a backyard otherwise covered with concrete. Flowers offer a rhythm to my summer and remind me of how time always circles back. In fiction they are even more eye-catching because I know they have not grown there randomly. A writer planted them there for some reason.

a cup of tea (1922)

‘I want those and those and those. Give me four bunches of those. And that jar of roses. Yes, I’ll have all the roses in the jar. No, no lilac. I hate lilac. It’s got no shape.’ The attendant bowed and put the lilac out of sight, as though this was only too true; lilac was dreadfully shapeless.

Her writing was the only writing I have ever been jealous of, Virginia Woolf writes of Katherine Mansfield. No wonder, really. Sometimes (only sometimes) I also prefer Mansfield to Woolf. Her stories are much more entertaining and dazzling. They punch you in the stomach and leave you dizzy, wondering and speechless such as no moment in any Woolf novel could ever do. Mansfield writes those half-ended endings, has those vivid and colourful descriptions and makes fun of those who deserve it here and there. Woolf pushes her questions of what each moment in life means to its limits and squeezes the last drop of life out of it. Mansfield leaves something for the reader as well.

‘A Cup of Tea’, a short story Mansfield published in 1922 in The Story-Teller is not really the typical Mansfield story. Rosemary Fell is not an innocent young woman who tries to figure out her way in the world, as most young women in Mansfield’s stories do. She is rich, really rich, married to a Philip who absolutely adored her and in the capacity to pretty much buy all the flowers at the florist’s. Except for lilacs, of course, for they are dreadfully shapeless. Heading home after admiring an antique shop, Rosemary meets a young beggar girl. She decides to take the girl home, offer her a cup of tea, and make her into her little charity project. But Rosemary changes her mind quickly when her Philip meets the young beggar girl.

Women and flowers are very present in Mansfield’s short stories. Flowers make for little patches of colour which liven up small, dark cafes or make a statement about the hat of a young woman of high society. Violets are Mansfield’s special favourite to use in poor settings, while canna lilies and roses decorate the drawing-rooms of the rich. In ‘The Tiredness of Rosabel’ Rosabel buys a bunch of violets and has barely any money left for tea and a scone, which make her meal for the day. In ‘The Garden Party’ Laura’s mother wants for once in her life to have enough canna lilies for her party. From rich to poor, flowers are there, either to bring simple joy or act as background decorations. It just makes me wonder if roses would bring the same joy to Rosabel and if Rosemary would find violets are dreadfully shapeless as lilac.

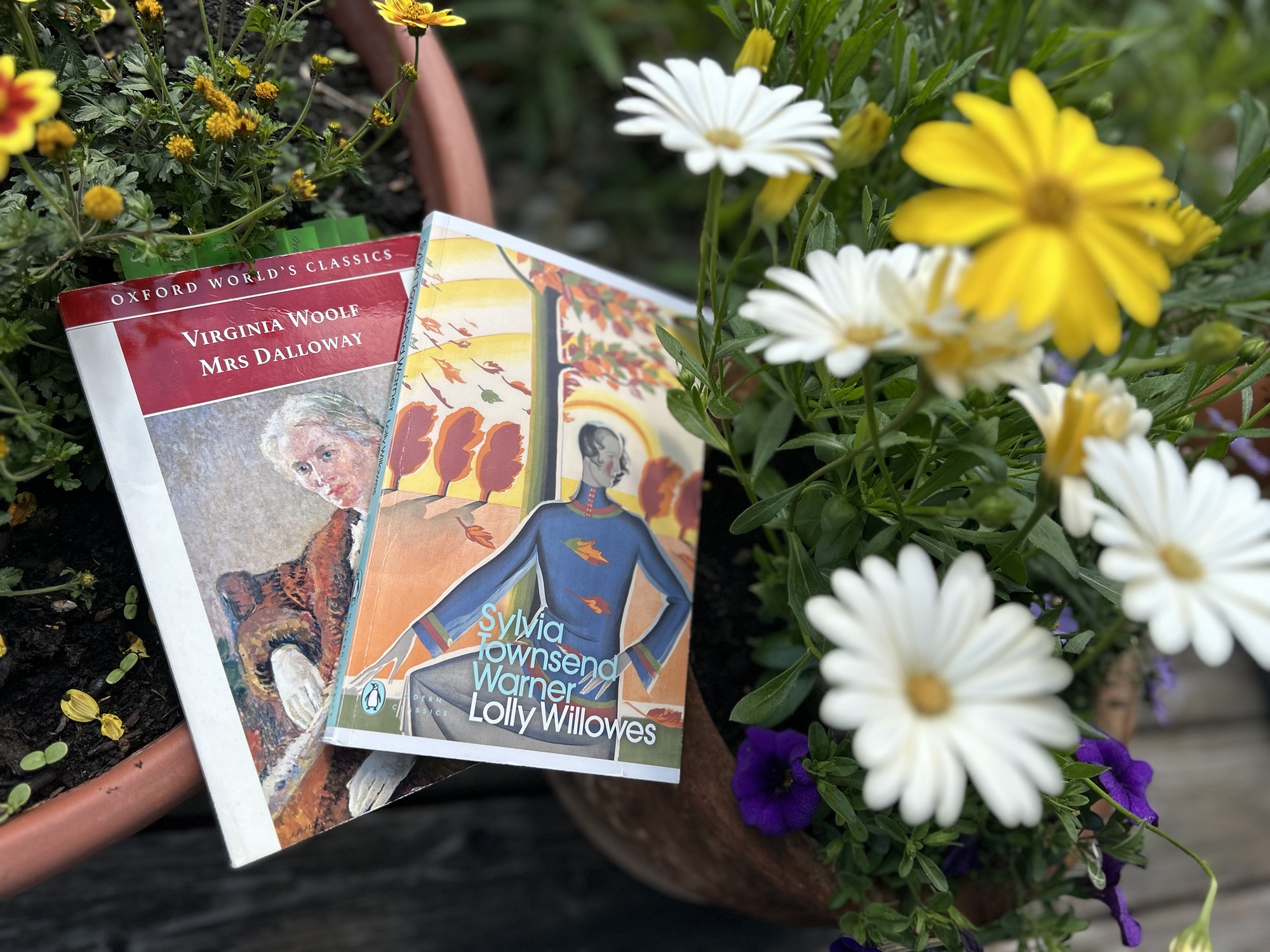

mrs dalloway (1925)

There were flowers: delphiniums, sweet peas, bunches of lilac; and carnations, masses of carnations. There were roses; there were irises. Ah yes – so she breathed in the earthy-garden sweet smell as she stood talking to Miss Pym who owed her help, and thought her kind, for kind she had been years ago; very kind, but she looked older, this year.

I will be reading Mrs Dalloway for the third year in a row and probably for the fifth time in my life. It feels so superfluous and limiting to say all those things people say and write about books. It was published in the year so-and-so (1925), it’s about this middle-aged woman, Mrs Clarissa Dalloway, who is planning a party in the evening, it is a landmark of Modernism. There, I’ve said it. I even said what it’s “about”. Ew. When reading it so often and living it each time I walk by a florist’s shop and digging it out of memory each time I cut a cauliflower open, how on Earth can I still say it was published in 1925 and all that? It’s crushing me. But it is of course far from crushing other readers, who might only know that Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.

Even though I’m acting high and mighty, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway is of course about Mrs Dalloway’s party, as it is about buying flowers, about walking the streets of London in the post-war years, about the highs and ups, the wins and losses in life, about memory, about friends, love, family death. And it all starts with Mrs. Dalloway going out to Bond Street to buy the flowers for her party herself. On her walk through the streets of London we hear her thoughts and jump around the chaotical insides of her consciousness, as each moment illuminates a spot in her life and memory. Peter Walsh would be back from India one of these days… Big Ben strikes the hour, irrevocable… Laughing girls taking their absurd woolly dogs for a run… Americans tempted by lovely old sea-green brooches… And so much more. Each line is life, a concrete whole and a fleeting nothing.

There are two moments in these first 10 pages of the novel to which I always pay extra attention. Scrope Purvis thought Mrs Dalloway a charming woman, and Miss Pym, the florist who owed her help, thought her kind. Looking from the outside in, when you know the in, is so deceptive. He is so friendly. She is so happy all the time. She always smiles at me. And their inside breaks. That hatred, that monster, surmount it all. And Scrope Purvis and Miss Pym only know her charm and her kindness. And what do we know? That Mrs Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.

lolly willowes (1926)

‘I want one of those large chrysanthemums’, she said, and turned towards the window where they stood in a brown jar. There were the apples and pears, the eggs, the disordered nuts overflowing from their compartments. There on the floor were the earthy turnips, and close at hand were the jams and bottled fruits.

Lolly Willowes was Sylvia Townsend Warner’s first novel. It’s a story of witchcraft, of the countryside, and of how society sees fit to handle women who decide not to marry. Lolly Willowes of the title is one of these women and her actual name is Laura. She becomes Aunt Lolly when, after the death of her father, her brother and his wife invite Laura to move in with them and act as a sort of unpaid governess for the children. She is given her own room, understanding and indulgence for her “extravagance” of filling her room with flowers in winter. What more could she want? The family can’t imagine there is so much more that Laura wants, and she can’t really express it herself, until, on an autumn day, she walks into a flower shop and decides to buy all the chrysanthemums.

I couldn’t find any information if Townsend Warner and Woolf knew or corresponded with each other. She did know members of the Bloomsbury group, but I couldn’t get any closer than that. Modernism and the flow of consciousness in writing were in the air though, and Townsend Warner’s style of writing is a bit like Woolf’s and Mansfield’s. But I think she doesn’t take herself half as seriously. If Woolf was invested in capturing the perfect fleeting moment and Mansfield’s short stories zero in on defining moments in her characters’ lives, Townsend Warner keeps a certain ironic distance. Just look at Lolly Willowes. A single woman past her youth moves to the countryside and turns to witchcraft to escape from a society which unjustly punishes her for her choices. What could Laura do? Shrug, revolt and turn to the only character in history who was as cast off as she was – Satan himself.

Flowers pave the way for Laura’s decisions, and stepping into the flower shop marks the point of no return. It is late autumn, and, as every year, Laura feels a sense of disquiet and longing and is overwhelmed by an unusual restlessness. Buying the chrysanthemums frees her and opens the door to a life she hadn’t realized she yearned for—a life of peace, independence, and freedom in the countryside. Chrysanthemums are for Laura not the excuse carnations are for Clarissa, nor the mere decoration roses are for Rosemary. She doesn’t look for idle beauty and fleeting enjoyment. For Laura flowers embody the life she has always wanted and could never live, a desire which has always been there and to which she has never given a voice. Until that moment in late autumn, which, for lack of a less dramatic word, I will call destiny.

Roses, lilac, carnations, lilies, chrysanthemums. Women characters in fiction each has her favourite, and that for different reasons. Could be age, could be time, could be an awakening to life. Symbols are endless and I will leave you to ponder on it. What I will do next time I see a flower growing out of the hands of a fictional woman is smile. I will imagine it in a garden, tended to somehow by a real woman. One of her joys or maybe her only, women and flowers are forever bound together.

your thoughts?