In her review of Virginia Woolf’s 1919 novel, Night and Day, Katherine Mansfield sharply criticizes the lifelessness of the characters that populate the novel. In her opinion, they are more on the side of writing, and less on the side of life.

We have the queer sensation that once the author’s pen is removed from them [the characters] they have neither speech, nor motion, and are not to be revived again until she adds another stroke or two or writes another sentence underneath. Were they shadowy or vague, this would be less apparent, but they are held within the circle of steady light in which the author bathes her world, and in their case the light seems to shine at them, but not through them.

Mansfield is clearly displeased with how minor characters such as Mrs. Denham and Sally Seal were penned. But what shines even clearer though her words is her belief in the sense of life which characters should give off. Strictly speaking, almost all characters in Katherine Mansfield’s short stories are minor because they all live just for a short while. But that’s not to say their life is contained in the stories. No, they jump off the page, they are more than their one short story.

In this third post of our mini-series on Katherine Mansfield’s short stories, I want to look at the dark details which let the characters continue their life outside the story’s borders. In pretty much every story there is a detail of violence and darkness which seems so out of place until you realize this is what real life is. In parallel with the Literature Cambridge course on Katherine Mansfield, my literary friend Gertrude and I previously wrote of some general characteristics of Mansfield’s style and what lingers long after the end of her stories.

ole underwood (1913)

Away below, the sea heaving against the stone walls, and the little town just out of its reach close packed together, the better to face the grey water. And up on the other side of the hill the prison with high red walls. Over all bulged the grey sky with black web-like clouds streaming.

‘Ole Underwood’ is one of Mansfield’s early stories, before she reached the full maturity of her Modernism. Ole Underwood, a former sailor, has just got out of prison, where he spent twenty years for killing the murderer of his wife. One evening, the old man goes to the pub, but he gets thrown out for crushing a vase of flowers. He stumbles in the direction of the wharf, where a ship lies as if waiting for him. Memories of the past come crushing back, as the sound of his heart pounding in his chest grows louder and louder.

You don’t have to look for long to find the darkness in this story. The atmosphere is drenched in it. The waves hitting the prison walls, the people gossiping the pub, the waitress who pays no mind to him and whose laughter is devoid of joy. We don’t get any insights in the thoughts of the old man, we only see what is happening on the outside and none if is helping his case – he scares away chicken and takes revenge on a cat wandering the streets. What does redeem him and makes him human is the only detail we know – the beating of his heart. That really stayed with me. For all the darkness and madness which pollutes his mind, there is a glimmer of humanity in that primal rhythm.

the stranger (1920)

But just as he embraced her he felt she would fly away, so Hammond never knew – never knew for dead certain that she was as glad as he was. How could he know? Would he ever know?

I’m not sure if there’s something such as a “typical” Katherine Mansfield short story, but if there were, ‘The Stranger’ would be one of those. It’s written along the lines of some of her more famous stories, such as ‘The Garden Party’, ‘Bliss’, or ‘Marriage a la Mode’. The intensity of the moment infuses these stories, and the perceptions of characters are defined by what happens around them. Mr. Hammond is impatiently waiting for his wife, Janey, to come off board the ship which has brought her back to him after a long journey. But he doesn’t simply miss her, he wants to physically and spiritually have her. His tragic moment unfolds when he realizes that an occurrence on the ship pushed Janey further away from him than he could have imagined.

The darkness which underlies the story is not so obvious as it is in ‘Ole Underwood’. The first disturbing thing which struck me was how tightly Mr. Hammond is hanging on his wife. “No more going without his tea our pouring out his own”. But that’s just the surface. He doesn’t offer Janey the space to be herself, he wants to invade the deepest corners of her persona, and know every bit of her. The second striking thing is the title of the story. I didn’t understand it at first. Who is the stranger? It could of course have something to do with the occurrence on the ship, but I think it has more to do with Janey. She can have her privacy only if, to some extent, her husband is a stranger to her.

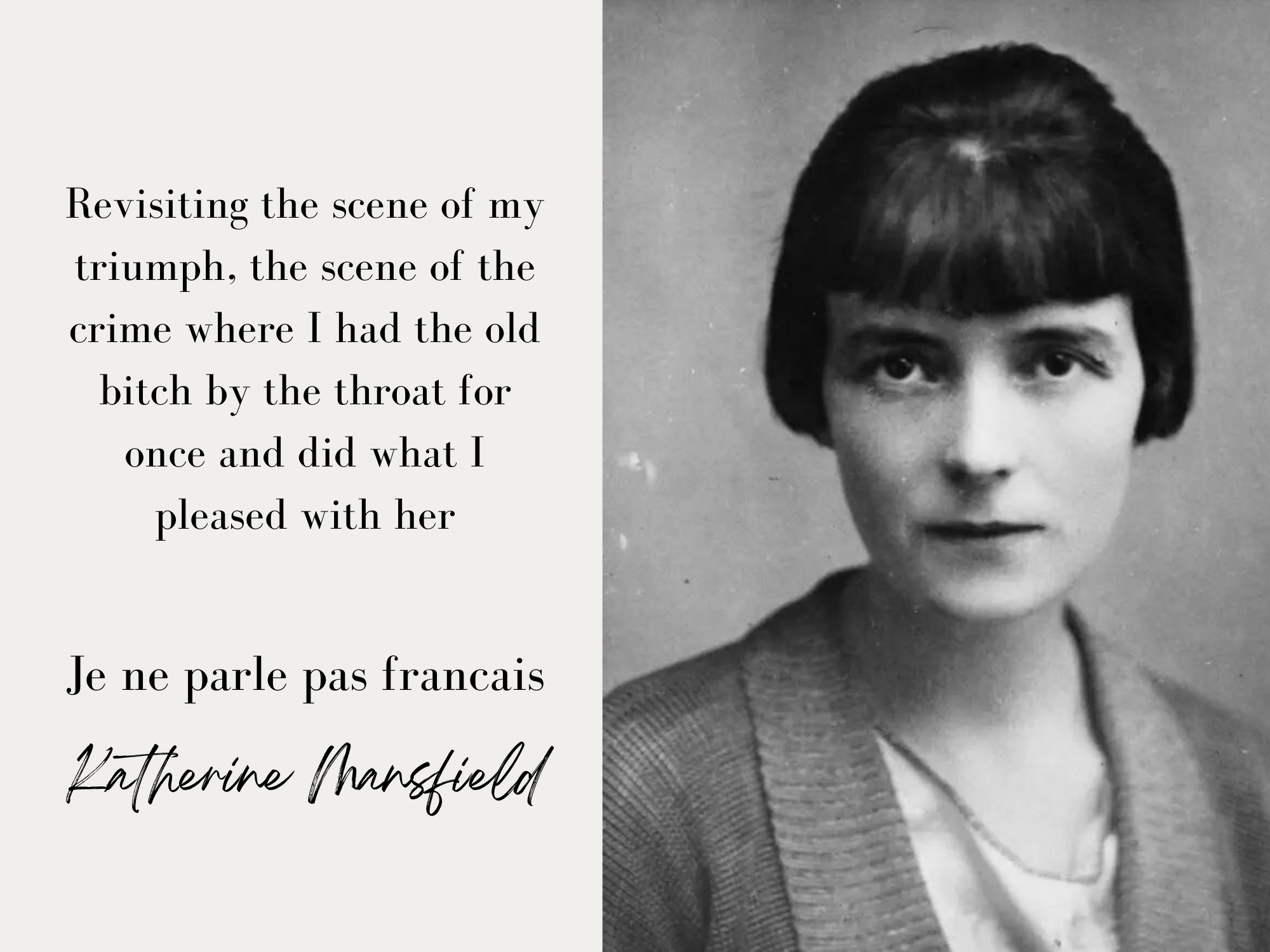

je ne parle pas francais (1918)

I don’t believe in the human soul. I never have. I believe that people are like portmanteaux – packed with certain things, started going, thrown about, tossed away, dumped down, lost and found, half emptied suddenly, or squeezed fatter than ever.

This story… Now this story is something else. I can’t fit it at all with anything else which Mansfield wrote and had a hard time wrapping my head around it. Raoul Duquette is our Parisian narrator, whose story starts in a sordid cafe, where a murder has been committed, the waiter is a favourite of the press for that, and Madame seems to wait for someone to come or for something to happen. Duquette goes through some details of his rough childhood, his failed attempts at being a writer and remembers at length an episode where a former lover of his, Dick Harmon, comes to Paris with Mouse, a woman whose memory shakes Duquette to the core.

I can’t say I lost sleep over Duquette, but even after reading the story several times, I still couldn’t get a proper reading of him. His memories lack substance and cohesion, Mouse is still only a shadow even though she’s supposed to have made an impression on him, and he seems more preoccupied with his image than with the interactions with other people. After Claire Davison’s course for Literature Cambridge, I got it. I think. For Duquette, nothing exists outside of himself. He gathers people and events inside himself like a portmanteau, but nothing ever really touches him. It’s not that other people are shadows, he is the shadow of others and a reflection of himself.

I went into the three stories only superficially. There is so much darkness left to discover. Is Ole Underwood mad when he steps aboard the ship at the end, or he just misses his wife? How much are we capable of knowing other people and who is the stranger in a relationship? There must be some sincerity in Duquette’s tales, but where is it hidden? Less answers and more questions after reading Katherine Mansfield’s short stories. As it should be I suppose.

your thoughts?