Just looking at the sheer amount, and Virginia Woolf’s essays can be quite intimidating. More than 600 essays published between 1904-1941 in a host of magazines on a host of subjects. Not positive here, but I’m pretty sure all of them have to do with literature somehow: book reviews, lives, walking in London, modern living, reading, writing, the nature of fiction. It all comes down to life and fiction one way or another. For her, life and fiction belong to each other and her life stands proof of her belief.

For me, more than being a writer, Virginia Woolf is a reader. Maybe that’s why I’m so taken with her essays more than with her novels or her short stories. In her essays, the reader side of her really sticks out. Sure, I could read To the Lighthouse once a year, but I could probably read, as you will notice below, ‘How Should One Read a Book’ and ‘Street Haunting’ once a week. In her essays, Woolf is playful. She starts here and ends there, gives her reader something only to take it away, interrupts her writing to go consult some 17th century writer I would have no chance of having heard of. In short, she makes you think, she makes you be there with her, she makes you put whatever you take from her essay back into your life. In other words, her essays change your life.

how should one read a book (1926)

“How Should One Read a Book” is not really a Google search someone who really wants to know how to read a book would start. They would type in something like “how to read a book” or “how to read a book a day” or maybe even “how to start reading”. While it would actually help, Virginia Woolf’s 1926 essay entitled quite so, “How Should One Read a Book”, doesn’t really show up in the Google top results on the topic. Maybe it should. I mean, Google is supposed to know what people want, right? Or maybe people want what Google gives them. Anyway, I’m digressing. Which, clearly, comes from too much Virginia Woolf essay reading.

Woolf loves digressions, interruptions, contradictions. Pretty much like this one. How should one read a book? You would be expecting a clear-cut answer. Instead, this is what you get:

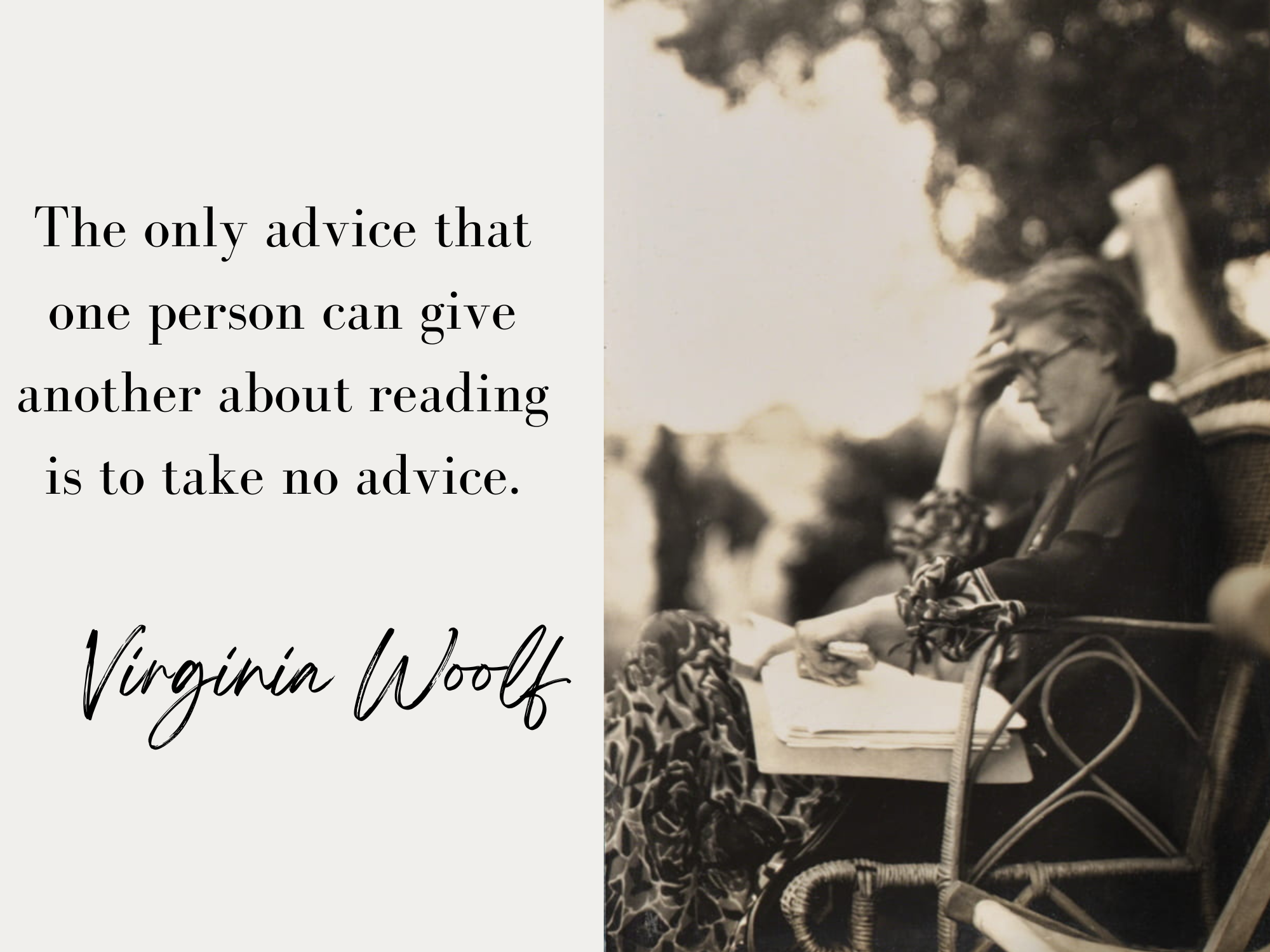

Even if I could answer the question for myself, the answer would apply to me only to me and not to you. The only advice, indeed, that one person can give another about reading is to take no advice, to follow your own instincts, to use your own reason, to come to your own conclusions.

So, basically, if you want to know how to read a book, better sit down and read a book. You read by reading. Probably the most sensible advice which can be given. As you read, your mind opens up and you follow pathways which flow out of your own life experience and of your own interests. Yet Woolf does provide some more practical advice. I’m just quoting a few. The essay is worth reading in all of its high intellectual splendor.

Do not dictate to your author; try to become him.

This is one of the ways in which we can read lives and letters; we can make them light up the many windows of the past.

Let us be severe in our judgements; let us compare each book with the greatest of its kind.

street haunting: a london adventure (1927)

For Virginia Woolf, reading is the embodiment of literature flowing from life and life fuelling literature. In ‘Street Haunting’ the narrator, or the essay persona, leaves her room under the pretext of buying a pencil, but with the hidden purpose of seeing life unfolding. At the end of the piece Woolf writes ironically: “And here is the only spoil we have retrieved from the treasure of the city, a lead pencil”. This is quite funny, of course, if you’ve been reading the previous 10 pages of small-printed and lacking-much-space-in-between sentences. The evening walk through London leaves the essay self with memories of past vacations, imaginary flights into the lives of other people, glimpses of the rich and the poor and, of course, books. And not just any books, second-hand books.

But here, none too soon, are the second-hand bookshops. Here we find anchorage in these thwarting currents of being; here we balance ourselves after the splendours and miseries of the streets.

Second-hand bookshops and street book markets are the best. You stumble into one of these unknowingly and get out, tired and happy and worried, with a couple of months’ worth of reading in a tote bag which you ideally carry around with you just for this kind of case. Tired because the number of books is unbeatable. Happy because the number of books is unbeatable. Worried because the number of books is unbeatable. Second-hand bookshops are, for me, a carousel of feeling. For Woolf, though, they are a source of life. She can’t hide in there from “thwarting currents of being”, because being comes flowing into her even more urgently.

There is always a hope, as we reach down some grayish-white book from an upper shelf, directed by its air of shabbiness and desertion, of meeting here with a man who set out in horseback over a hundred years ago.

This little book of poems, so fairly printed, so finely engraved, too, with a portrait of the author. For he was a poet and drowned untimely.

Thinking, annotating, expounding goes on at a prodigious rate all round us and over evertyhing, like a punctual, everlasting tide, washes the ancient sea of fiction.

You can’t read Virginia Woolf’s essays and keep your life the way it was before having read them. They bubble with life and movement, they are imaginative, curious and cheeky at times, they give you ideas to try out for yourself. Such as comparing random contemporary authors with the master Modernists. Or looking at the back of second-hand bookshops where cheap volumes lie forgotten. Who knows what else might be to discover.

your thoughts?