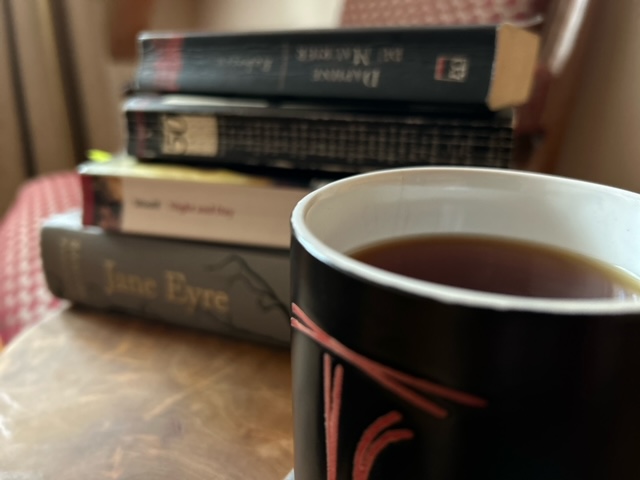

Drinking tea while reading. Putting up your warmly wrapped feet (usually in socks sporting a Nording pattern) by the fire while enjoying a cup of tea. Shopping for expensive tea at “Fortnum & Mason” on the high streets in London. These are all tea stories we hear (or see) told when browsing Instagram or, really, when we think about tea at all. They are so common, that they are almost clichés by now. Yet there is unmistakable joy I, for one, feel when thinking about the hot brew of Darjeeling and the book I’ve left open next to my reading armchair. And the joy gets bigger when tea is featured in the book I’m reading.

Over the past months, I’ve been gathering tea quotes from the books I’ve read. But don’t expect cosy fireplace moments, metaphors for life, or profound pieces of wisdom from ancient rituals. In the quotes I’ve gathered, tea is the behind-the-scenes character who tells a larger story than the one which is immediately apparent. My tea quotes reveal a bit of comfort in the face of hardship, memories which gain new meaning with time, customs which definitely don’t sit well with everyone involved and a woman who takes said customs and turns them in her favour. So sip along with me and let the flavour of tea cast away the unseen and unacknowledged.

charlotte brontë Jane Eyre – the comfort of tea

A little solace came at tea time, in the shape of a double ration of bread – a whole instead of a half-slice – with the delicious addition of a thin scrape of butter; it was the hebdomadal treat to which we all looked forward from Sabbath to Sabbath. I generally contrived to reserve a moiety of this bounteous repast for myself; but the remainder I was invariably obliged to part with them.

Charlotte Brontë published Jane Eyre in 1847, under the pseudonym of Currer Bell. The story is fictional, yet it draws on her own experiences – the death of two of her sisters of tuberculosis while at Cowan’s Bridge school, the unrequited love Charlotte felt for the married Heger while studying in Brussels, being student and then teacher at the Roehead school for girls.

I took the quote above from the first part of the book, after Jane’s cold aunt, Mrs. Reed, sends Jane to Lowood, a school for poor and orphaned girls. Lowood is run by Mr. Brocklehurst, a clergyman who is set on teaching the students humility and obedience while almost starving them and keeping them in harsh conditions. At Lowood food is never enough and a place by the fire in winter must be fought for. Teatime is one of the few comforts Jane has, when a cup of lukewarm tea is served with a slice of bread, thinly smeared with butter. Tea is but poor comfort for young Jane, and memories of Lowood are not pleasant for adult Jane, but they do serve as elements to which her later determination and resilience can be traced back.

daphne du maurier Rebecca – memories of tea

Poor whims of fancy, tender and un-harsh. They are the enemies to bitterness and regret, and sweeten this exile we have brought upon ourselves. Because of them I can enjoy my afternoon, and return, smiling and refreshed, to face the little ritual of our tea. The order never varies. Two slices of bread and butter each, and China tea. What a hide-bound couple we must seem, clinging to custom because we did so in England. Here, on this clean balcony, white and impersonal with centuries of sun, I think of half past four at Manderley, and the table drawn before the library fire. The door flung open, punctual to the minute, and the performance, never-varying, of the laying of the tea, the silver tray, the kettle, the snowy cloth.

Rebecca was published in 1938, the fifth novel of English writer Daphne du Maurier. The story of Rebecca traces closely the story of Jane Eyre, while Mrs. De Winter and Rebecca act as a sort of alter egos to Jane and Bertha. In both stories memory plays a large role. Jane and Mrs. De Winter tell the stories of their lives from the point of view of experienced adults, who have known hardship, rejection and, in a way, resurrection.

I took the quote above from chapter 2 in the book. The novel opens with mature Mrs. De Winter, reminiscing about her youth days, when she met her husband, Maxim De Winter. Back then she was a nameless, shy girl, the companion of the rich and old Mrs. Van Hopper. When Maxim de Winter asks her to marry him, she says yes and moves to Manderley, the state home of the De Winter family. Teatime was set in stone at Manderley, always at half-past four, when cakes were served along with tea. This is just a memory now for Mrs. de Winter and her husband, self-exiled to Italy, as we can assume, strangers who cling to a custom existent only to themselves.

virginia woolf Night and Day – the custom of tea

It was a Sunday evening in October, and in common with many other young ladies from her class, Katharine Hilbery was pouring out tea. Perhaps a fifth part of her mind was thus occupied, and the remaining parts leapt over the little barrier of day which interposed between Monday morning and this rather subdued moment, and played with the things one does voluntarily and normally in the daylight.

Night and Day, published in 1919, is Virginia Woolf’s second novel. Much like The Voyage Out, Woolf’s first novel, it does not completely break with Victorian-style narrative, but it does open new paths which Woolf will eventually take to write her Modernist masterpieces, Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse. Night and Day is a rather intimidating 400-page novel, which mostly deals with young Katharine Hilbery’s attempts to escape her Victorian upbringing, women’s suffrage and the question of marriage.

The quote above is the very opening of the novel. The Hilberys are entertaining guests at their home in a rich area of London and Katharine, like the good daughter of a wealthy and literary family she is, is pouring out tea for the guests. The scene where the woman pours out tea to husband, father or guests is a fairly common image one encounters when reading early 20th century English literature, and is a mark of class and the different places men and women had in society. Katharine does fill her place, at first glance, but her mind and her thoughts and somewhere else entirely. As the narrative progresses, Woolf rises against these social conventions, in a nuanced exploration of gender roles and the fight for women’s right to vote.

edith wharton ‘The Other Two’ – against the custom of tea

She swept aside their embarrassment with a charming gesture of hospitality.

“I’m sorry – I’m always late; but the afternoon was so lovely.” She stood drawing off her gloves, propitiatory and graceful, diffusing about her a sense of ease and familiarity in which the situation lost its grotesqueness. “But before talking business,” she added brightly, “I’m sure everyone wants a cup of tea.”

She dropped into her low chair by the tea-table, and the two visitors, as if drawn by her smile, advanced to receive the cups she held out. She glanced about for Waythorn, and he took the third cup with a laugh.

‘The Other Two’ is a short story by Edith Wharton, published in 1904. The story is quite strange, I can’t really tell if it is meant to be satirical, humorous or critical. It is told from the point of view of Mr Waythorn, who is plagued by doubt and jealousy, as the two former husbands of his wife, Alice, are suddenly involved in his family life. Mr. Haskett is Alice’s first husband, by whom she also has a daughter who has fallen ill, and Mr. Varick is her second husband, whom Waythorn serves as his client at his investments firm.

The quote above makes the very ending of the story. Alice, her two former husbands and her current husband have all met by coincidence at the Waythorn’s house. The situation is clearly uncomfortable, especially for Waythorn, who finds himself in a tight spot before Alice makes her appearance. In this tight atmosphere, the custom of afternoon tea is almost a rescue. Alice, the figure who connects the three men, is happy to fulfill her role of pouring out tea, and she clearly uses the situation to her own advantage. As I see the scene with my mind’s eye, Alice uses the teapot and the teacups as instruments of diplomacy and asserts firm control over the situation, as well as her own independence.

In this post, I let Charlotte Brontë, Daphne du Maurier, Virginia Woolf and Edith Wharton tell you some tea stories, which are wildly different from the ones we know nowadays from our pop culture. Maybe they will inspire you to reconsider that Instagrammable cup of tea you enjoy while reading a book or after a long shopping session on the high streets of London. Comfort? Memory? Custom? Does tea mean any of these to you? Or maybe it means so much more. Do let me know.

your thoughts?