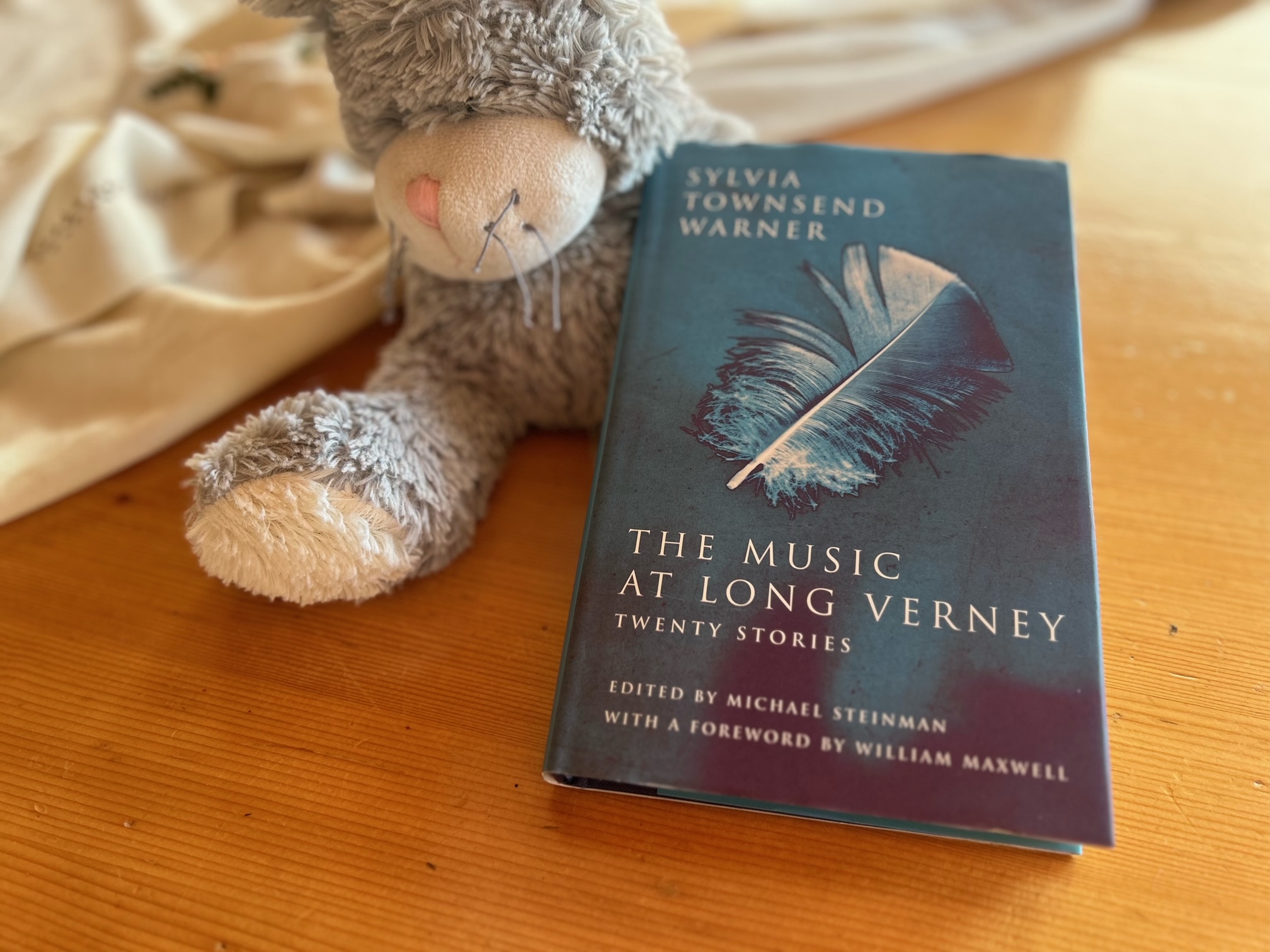

I stumbled upon the name of Sylvia Townsend Warner some years ago, when I was studying Modernism. Now, after having read Sylvia Townsend Warner’s posthumously published volume of uncollected short stories, The Music at Long Verney, and her first novel, Lolly Willowes, I am amazed I didn’t come across her sooner. Her writing is funny, ironical, satirical at times even, beautiful and precise. Within a short story of 7-8 pages long, she manages to draw out the nebula of the human soul traits which connect us, people, to other people. On a par with Virgina Woolf and Katherine Mansfield, Sylvia Townsend Warner is slowly climbing to the top of the list of my favourite authors ever.

The New Yorker featured more than 150 of Sylvia Townsend Warner’s short stories, and most of them were published in collections during her lifetime. But 20 of them escaped somehow, until Michael Steinman, who is also the editor of her letters, dug through the archives and found the little treasures. The Music at Long Verney is a pure joy to read. Delightfully captivating, the stories span different periods in Townsend Warner’s life, yet a subtle, invisible thread weaves them together. Each story centers on a little fleeting moment in someone’s life, a moment which illuminates the character’s life or even defines it. Whether portraying men and women entangled in the memory of their past, or caught in a lack of understanding of one another, the stories culminate in a precious moment of connection. Or at least that’s what some characters perceive the moments to be. The author’s laser gaze switches from the inside to the outside of a character’s point of view, and makes us realize that we are all stories in the eyes of other people.

The trick of most of Sylvia Townsend Warner’s uncollected stories is that they start with an object or a place, only for the reader to realize that objects and places are ways into the inner worlds of the characters. The first group of stories takes the reader into different kinds of houses and shows that houses can be places of both the known and the unknown in our lives. Then there are the stories about unknown and unknowable women, out of which I selected ‘A Scent of Roses’ to write more about below. The Abbey Antique Galleries is an antique store and the owner, Mr Edom, has meaningful encounters in each of the five stories which make up this mini-series. ‘The Listening Woman’ was my favourite from the group. The final stories are mostly about art and creativity, and look closely at creator, creation and public. ‘Item, One Empty House’ is one of them.

a scent of roses (1972)

During the next ten years he loved her with all his cold heart. She never changed her scent, so it seemed to him she grew no older. She contented him. She was one of her Regulars – she concentrated on Regulars.

I really thought long and hard about whether my favourite was ‘A Scent of Roses’ or ‘Love’. Both stories have at their heart men who think they understand women, while the relationships between said men and said women are wildly different. ‘Love’ is about a married couple who wants to buy a house and ‘A Scent of Roses’ is about a man and a woman engaged in a, to use a euphemism, “casual” relationship. I chose the latter to be my favourite in the end because it makes a stronger point. Howard meets Millie during the war, as she offers help to wounded soldiers, and their relationship begins when he visits her to return her handkerchief. Howard lived under the shadow of his mother and is cold in his scant relationships to women, but in his 10-year relationship to Millie he finds something to hang on to. But when Millie ends their relationship abruptly, Howard is furious and wounded. The story ends as he realizes his own feelings and how little he knew about Millie.

the listening woman (1972)

It is common experience how the possessions of one’s childhood vanish: the blue and white mug with D on it, picturing a dog and a duck and a dairymaid, and at the bottom when you have drunk up your milk, a daisy; the ombres chinoises marionettes with strings attached to their joints […] all scattered, all gone, broken or left behind in house moving or given away.

This story is part of a mini-series of five short stories, centered around the Abbey Antique Galleries, which were published in The New Yorker in the 1960s. ‘The Listening Woman’ is the last one of them, published only in 1972 because apparently her editor, William Maxwell, got bored with the series. I really wish there was more of it. In each story Townsend Warner looks at the owner of the store, Mr Edom, and at one or more of the customers which come to visit. The delicate way in which she explores the intentions of the visitors, either to buy or to sell, and the ironical way in which she looks at the knowledgeable and a bit stuffy Mr Edom is simply delightful. She entertains and reveals human character at the same time.

The story pictures elderly Miss Wainwaring who visits Mr Edom’s store by chance and finds a portrait which used to hang on the walls of her grandfather’s house and of which all traces were lost in time. It was Miss Wainwaring favourite painting, and seemed to change and reveal more of itself, as young Lucy Wainwaring grew up and discovered more of herself and of the world. The point of view in the story changes between the elderly lady, lost in her memories, and Mr Collins, Mr Edom’s assistant, who has no understanding of what the elderly lady is going through. By a stroke of luck, Mr Collins overprices the painting, preventing it from being bought by other customers and, when Mr Edom makes his appearance, Miss Wainwring purchases it. The story also has autobiographical elements, for the painting in the story belonged to Townsend Warner’s family and can now be seen at the Dorset County Museum.

item, one empty house (1966)

I told him I had also read about New England in the stories of Mary Wilkins. He replied with an Indeed; and reinforced the effect of the withdrawal by adding that she wasn’t thought much of now.

This was probably the most surprising short story of Sylvia Townsend Warner’s uncollected stories. Even though I can hardly call it a short story. It reads more like a nonfictional essay and its style reminds me of the essays of Virginia Woolf, such as ‘A Room of One’s Own’ and ‘Street Haunting’. The narrator leaves her native England and makes a visit to Connecticut, where she is invited to a house party. Much as Woolf in ‘Room’, Townsend Warner takes the reader by the hand and invites us to tread the complicated pathways of her thoughts, as she contemplates the surroundings of the house in Connecticut and her recent reading of the American author Mary Wilkins. She wonders why Mary Wilkins isn’t “thought much of now” and makes a strong case for ‘A New England Nun’, which I’m strongly inclined to read now.

This has been a great start to the year for me. I returned to Mircea Cărtărescu, one of my favourite authors ever, and I have discovered Sylvia Townsend Warner, through whose list of works I will carve my way in the next years. Short story collections, novels, letters, the list could be endless. Let me know if she’s on your list of favourite writers and what I should read next from her.

your thoughts?