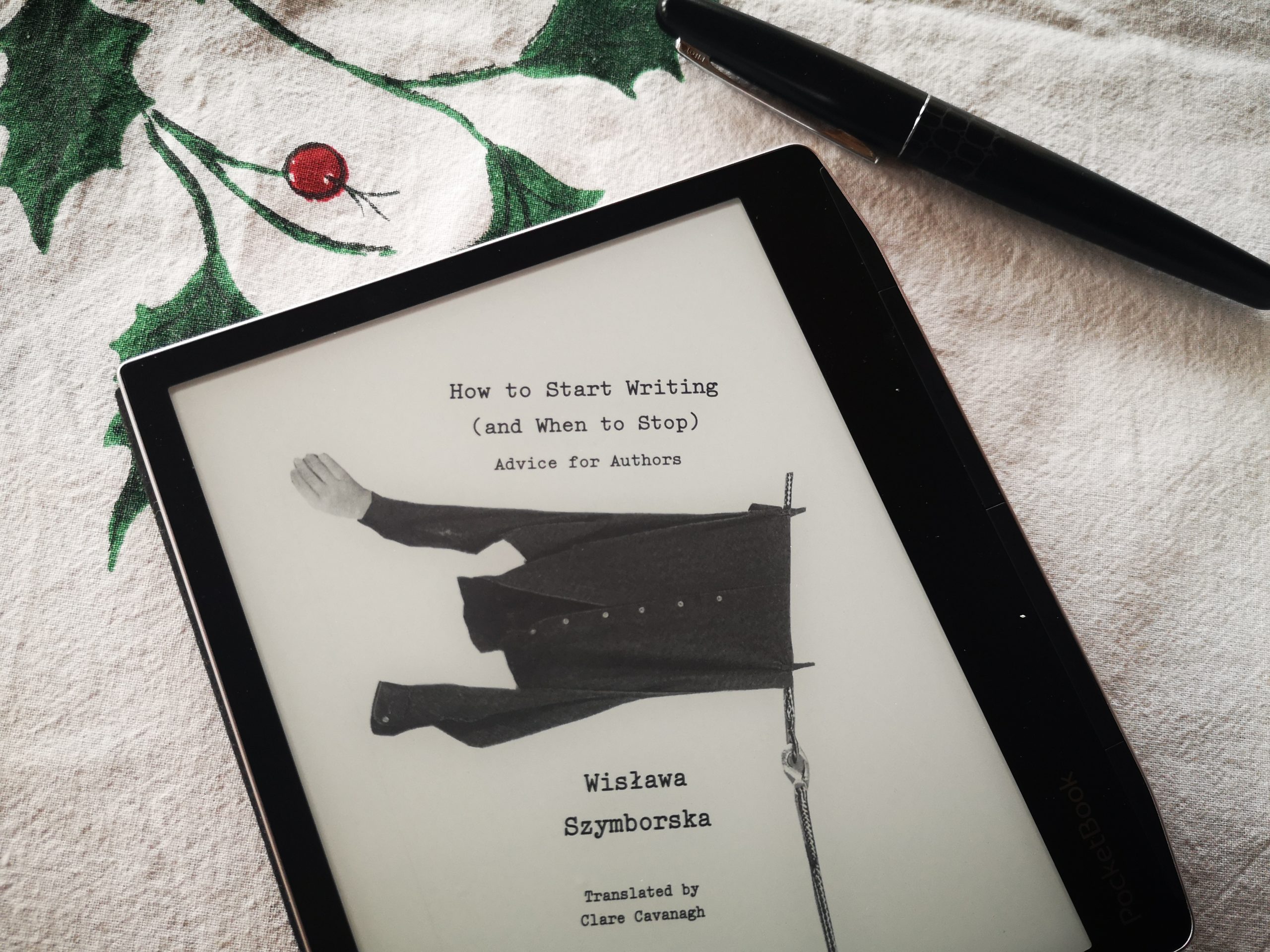

That Wislawa Szymborska was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1996 is something one can find by simply searching for her name. That How to Start Writing (and where to stop) is a collection of responses to literary attempts of readers of the Polish journal Literary Life is the first thing one reads in any review. So I will not say any of that. What I will say is what perhaps no review will tell you and no search will reveal: the title is misleading, a joke at the expense of all creative writing courses and of all shelves filled with titles such as “How to write a novel,” or the even shorter “How to write.” This is not a guide on how to do all that. But I see I’ve used too many negatives in this first paragraph.

This is a book which demands unconventional, free, creative reading. You can leisurely open the book in the middle or towards the end, read two or three pages and then set it aside. It reads like listening to someone speaking on the phone – you grasp only half the conversation, but you have no problem, and even rather enjoy, imagining what the other side said. You are privy to dozens of halves of conversations, and you form your own image of the actual parties involved – art, writing, life.

writing advice… kind of

Even though I mentioned earlier that the title is misleading, the way Szymborska responds to would-be novelists, poets and translators is nothing less than a writing masterclass. One doesn’t need writing strategies and things to be taught in a school-like way when one is brave enough to join in her language games. Her replies are at times so sophisticated, laden with irony, formalities and cultural references, that even multiple readings still leave some of her meaning shadowed. She’s ironic and funny, tramples over tired metaphors and encourages active engagement on the reader’s side. She admits that Harry from Szczecin is right when he points out that there are countless examples of well-known writers who in their early careers had to deal with editors rejecting their work. Showing no remorse, Szymborska promises Harry that the samples he sent will “certainly be included in your Collected Works as long as you produce something along the lines of David Copperfield.” A.P. from Bialograd receives one of the shortest replies of all: “You’re right, autumn is sort of sad somehow.” She is unforgiving. One almost feels sorry for the courageous senders of lyrical attempts. Almost.

Yet Szymborska shows sympathy many times as well. She prescribes impossible amounts of reading, recommends using the paper bin as often as possible, and writing to exorcise errors. To W.S. from London she recommends “wider reading, less writing and more local observation, and raising only questions that have answers.” This is sensible advice, and, to the reader toying with the idea of writing herself, it also feels like it’s nothing new. Irony aside, this is probably as old as writing itself. Anything else is excuse and procrastination. Of course, it might be useful to visit a storytelling course to be told that you need to grab the reader from the very first sentence, or that you must construct a hero or heroine who changes as the story progresses. Szymborska offers T.K. from Plock a short version of that, though: “In a pinch, a story can make do with no opening or conclusion. The middle, though, is nonnegotiable.” Not sure about other readers, but I for one would like to have this tattooed on my brain.

language criticism

Beyond that, there are no rules, Szymborska says in these paragraphs. The “contradictions” which arise at times stand proof of that. That a writer can’t commit to plain language and can’t commit to pretentious language, she makes clear in two different replies. To B.K.L from Zgierz she writes “Who says “numerous”, “multiple” or “great” these days? No, it’s just a “lot”.”, while to Ka-ma she writes “Betty no longer has a kitty. Now Betty possesses a cat”. She is a poet, but is not hiding behind euphemisms and is not downplaying the value of a concrete word: ““Mailmen” are not “postal carriers” or “correspondence distributors”,” she points out to L.O. 88 from Nowa Huta. This is social and language criticism at its finest.

If you’re looking for a guide on how to start writing, this is not for you. If you are looking for cultural entertainment and words of wisdom from the editorial world, with a side of irony and humour, be sure to pick this up. Like me, you might end up learning some old new things on the way.

your thoughts?