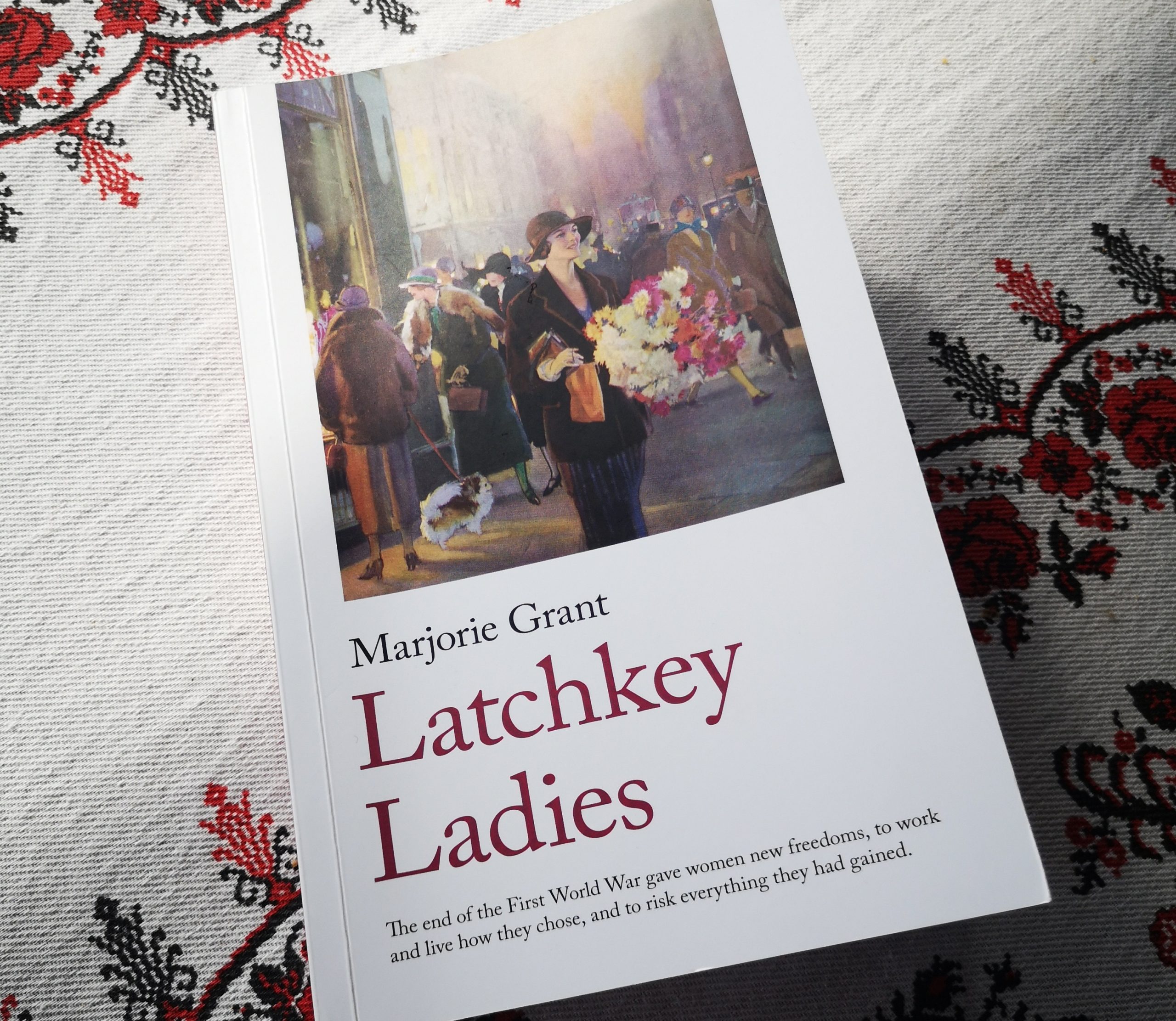

‘The Virgin Mary’s Child’ is a fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm at the beginning of the 19th century. In the story, the Virgin Mary adopts a baby girl whose parents are too poor to feed her anymore. When the girl turns 14, the Virgin Mary leaves her alone in Heaven for a short while and gives her all the keys to all the doors, asking her not to open the thirteenth door. The girl does open it (obviously) and, as punishment, is cast out of Heaven. The protagonists of Marjorie Grant’s 1921 novel, Latchkey Ladies, are, like the unnamed girl in the Grimms’ fairy tale, in possession of the key to “a garden of magic” (as Anne Carey, one of the ladies in the title, bitterly puts it). But their freedom is not all that they dreamt of. If they don’t stick to the rules which society laid down for them, their freedom will turn out to be a pumpkin. For it comes with strings attached.

the short of it

Anne is the New Woman of the beginning of 20th century England: she is educated, has a job which provides her with a stable income and, what is perhaps most precious, has “a room of her own.” But she’s not a writer of highbrow literature, and work is a practical necessity. The events in the novel unfold against the backdrop of WWI and Anne is an employee in a Government office, sorting through official documents. She puts up with this job, though she dreads it, and maintains a precarious balance of power with her male co-workers.

The reader realizes in the very first chapters of the book that Anne’s life is waking up from the romanticized dream Virginia Woolf was to write about in A Room of One’s Own some eight years later. Anne is perfectly aware of where she stands: “Latchkey ladies […] being independent and hating it. All very well for people with gifts and professions, artists or writers. But for us, the ordinary ones, a latchkey is a terrible symbol. I must be old-fashioned and domestic at heart.” And that she indeed is. She dreams of a life in the countryside and children but wouldn’t admit that to her “latchkey friends.” She is torn between enjoying modern freedoms and heeding the call of her innermost self. Nothing much different from what the 21st–century woman struggles with, really.

anne’s latchkey friends

Petunia Garry is a frivolous “latchkey lady” with what seems to be a colonial background. She’s one of Simon Meebes’ “pretty ladies”, and the reader can only guess what is happening in the background. Using Simon’s “allowance”, Petunia enjoys buying clothes, but she’s also fond of window-shopping and telling an ever-changing story of her origins. She falls in love with a soldier from a rich family only to realize that, as his wife, she “must wear the family things and take the same pride in them that we do”, as Robert, her future husband, sternly puts it. Anne is also aware of how Petunia is changing and is often sarcastic towards Robert and his intentions of turning Petunia into the wife he and his family wish for.

Robert, like the other men in the novel, is rather flat. His only drive and motivation as a character is to marry the woman of his making. Philip Dampier is not very believable as Anne’s lover and Carmichael, Philip’s friend, is impossibly noble in his readiness to offer his help to Anne when he believes she finds herself in need. Even though I likened Grant’s novel to a fairy tale, WWI London is not the setting of a fairy tale where the knight comes riding on his white horse and saves the damsel in distress. Anne says, “I don’t consider myself a victim and that though I’m unhappy I’m not ashamed, not anxious to be ‘righted’”. These women know what they are doing and the risks they are taking. The time for dreaming and waiting is over.

Over the course of the novel, we meet more of Anne’s friends, who go and make lives for themselves, using the tools this new world puts at their disposal. Sophy Garden, young and impressionable, has “never been to theatre without a man”, while Maquita Gilroy, a spirited woman, of “rowdy” manners, is probably the one enjoying her freedom to the fullest. We also encounter the morals of the Victorian age, personified Anne’s two aunts. Even though they have, or strive to achieve, modern views, they are part of the patriarchal society who holds the reins and lays down rules of behaviour for young women.

freedom, work in progress

Anne, Petunia, Maquita, Sophy. They have all the keys to all the doors. Yet if they open the wrong door, there are consequences to be faced. They must either let go of themselves or society will let go of them. In its layers of irony, Marjorie Grant’s Latchkey Ladies suggests that when living in a society which has its limits in tolerating it, freedom is still a work in progress.

your thoughts?