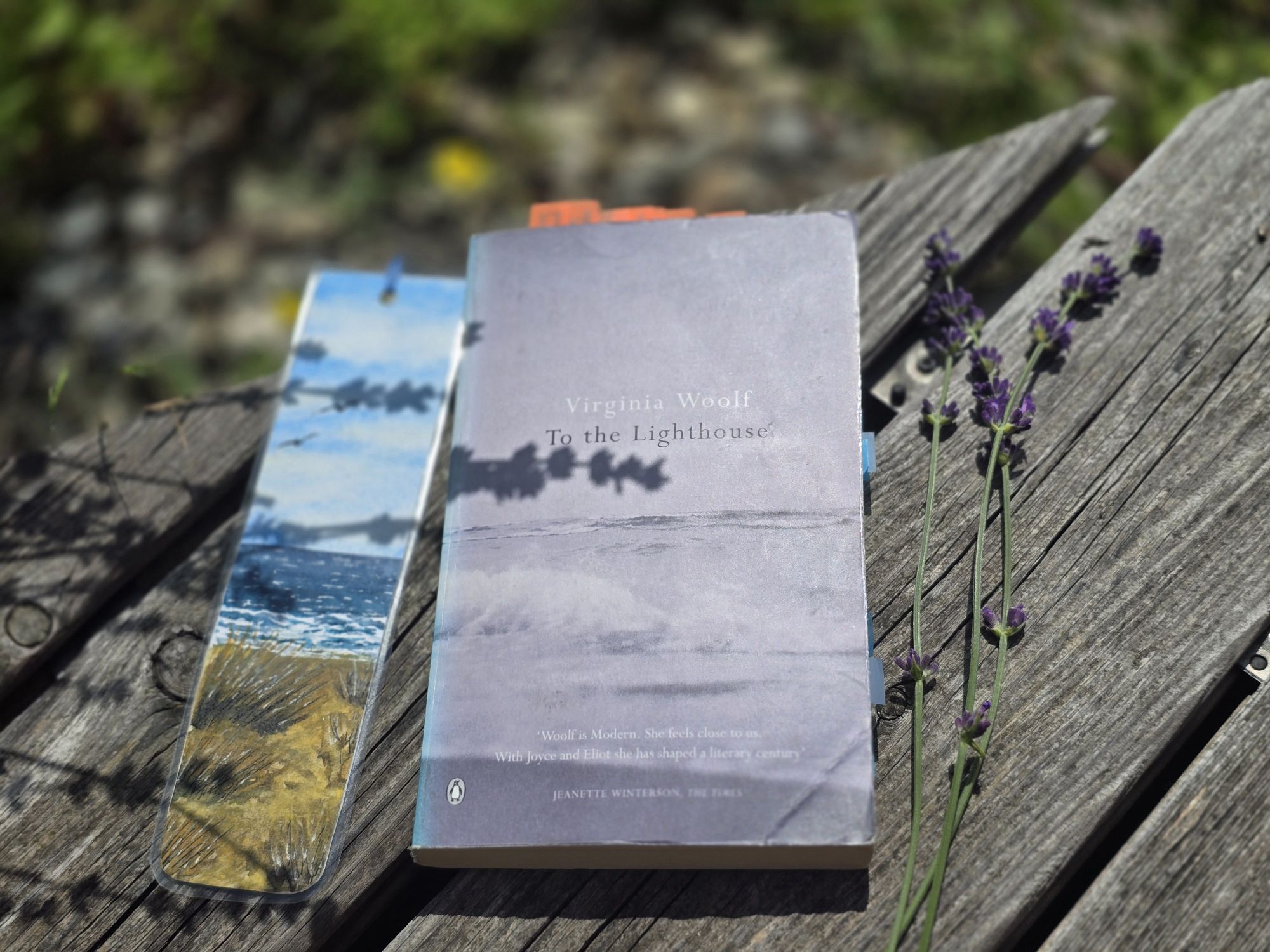

There’s something painful and true about To the Lighthouse. In a diary entry from June 1925, Virginia Woolf confides that she doesn’t even want to call it a novel. “A new – by Virginia Woolf. But what? Elegy?” she wonders. And that’s one way for the modern reader to understand her book – an elegy for her mother, but also for her childhood, a whole world lost to time. Woolf plans for the book to echo the rhythms of childhood summers she spent with her family in their vacation home, Talland House in Cornwall: “The sea is to be heard all the way through it.” She works on the book for months, until February 1926, when she notes that “what fruit hangs into my soul is to be reached there.” In To the Lighthouse, Virginia Woolf reaches into her own past, the ghosts of which she resurrects to shape memory and mourning into something lasting.

summary of to the lighthouse by virginia woolf

To say that any of Woolf’s novels have a “storyline” feels to me rather misleading (don’t want to say “sacrilege”, but not really far from that either). In To the Lighthouse, the narrative, if we can call it that, works more like a canvas for the painting of characters who are infinitely more complex than the 200 pages of “story” they go through. The Ramsays spend summer at their vacation house on the Island of Skye, and the novel opens with a discussion between James, the youngest of the eight children, and his parents. James wants to visit the lighthouse, and his mother and father see his childish wish in different ways. The family is joined by their friends: the painter Lily Briscoe, Charles Tansley, a student of philosophy and admirer of Mr. Ramsay’s work, Augustus Carmichael, a poet slowly reaching old age, and a young couple formed of Paul and Minta, who Mrs. Ramsay would very much like to see getting married. The novel explores the inner lives of the characters over the course of a single day, then dramatically lets war and 10 years pass in a few pages, to turn again towards personal and social changes which leave everyone emotionally scarred.

the childhood of virginia woolf

Stating that Virginia Woolf had a happy childhood or that Virginia Woolf had a restrictive childhood would be overly simplified and crude. She was born in 1882, in the late Victorian age, in the intellectually rich Stephen family. Her father, Leslie Stephen, was a respected literary critic and historian, who spent years of his life working on the Dictionary of National Biography and her mother, Julia Stephen, was a woman of striking beauty and a selfless figure who had been a model for painters and a near-mythical presence in Virginia’s early life. The family was what we would call today patchwork. Both Leslie and Julia had children from previous marriages – Leslie had a daughter, Laura, and Julia two sons, Gerald and George, and a daughter, Stella. Together they had four more children. Their daughters, Vanessa and Virginia, showed talent for painting and writing at an early age, but it was the sons, Adrian and Thoby, who were sent to study in Cambridge. With 10 people in the household, countless guests and family members coming and going, there was little place for privacy, but more than enough for communal creativity. The children “published” their own newspaper, Hyde Park News, writing articles about family events, stories and inside jokes. When Julia died suddenly in 1895, Virginia was just thirteen. The loss shattered her. In many ways, To the Lighthouse is her way of healing that wound, mourning her mother and freeing herself from her ghostly presence, as she wrote in the autobiographical essay A Sketch of the Past much later, in 1939.

Some of Woolf’s happiest memories came from the times the Stephen family spent in St Ives, Cornwall, at Talland House. It was in 1882, in the summer of the year Virginia was born, that they spent their first vacation there. The vacations would continue every year, until 1895, when Julia died. The sea, the lighthouse in the distance, the garden – all these places etched themselves into Virginia’s memory and her imagination. Those long summers gave Woolf a sense of freedom that contrasted with the restrictions of Victorian London life. Decades later, when Woolf was in her 40s, they became the raw material for To the Lighthouse. In the fictional house on the Island of Skye, she revives her childhood summers and recreates the feeling of a time when her mother was still alive, the days seemed endless, and her family was still whole.

life and fiction

Saying that Virginia Woolf wrote with To the Lighthouse an autobiography or that she wrote a novel based on her childhood would be another crude simplification. In 1925, when she started working on the book, Woolf had already written Mrs Dalloway. She was already in control of what we know today to be the modernist technique of free indirect discourse (letting her characters speak in their own voice as if they are possessing the narrative) and a mistress of her craft. Besides, she didn’t believe in genre – novel, essay, biography, and especially fiction, all entangle to create the woolfian pieces of writing we read and love today. I believe that what she’s doing is create a tunnel, a dialogue between herself and her past. She paints a textual portrait of her memories, and of her mother, to be able to see her as a woman, and come to terms with all the facets of her personality, especially the contradictory ones.

There are of course a lot of facts we can pick out from Woolf’s life and map on events in the novel. The Stephens and the Ramsays both have 8 children. Mr Ramsay is obsessed about not being able to reach letter R of the alphabet, a hint to Leslie Stephen’s life work. Mrs Ramsay dies suddenly, and years pass before the children visit Isle of Skye again, which is what happened with Julia Stephen in real life as well. But the strongest acknowledgement comes from Vanessa, Virginia’s close sister, who writes to her in a letter short after the publication of the novel:

You have given a portrait of mother which is more like her to me than anything I could ever have conceived possible. It is almost painful to have her so raised from the dead […] You have given father too I think as clearly, but perhaps, I may be wrong, that isn’t quite so difficult. There is more to catch hold of.

Letter of Vanessa to Virginia, 11th May 1927

Woolf understands her parents through the perspectives of Mr and Mrs Ramsay and explores the emotional weight they left behind. She turns them into characters shaped by memory and mourning. Mr Ramsay, like Leslie Stephen, is brilliant and admired, but also constantly needing reassurance, particularly from his wife, that his work and intellect still matter. A scene at the beginning of the novel shows him pacing on the lawn, muttering Tennyson to himself, while intruding on the privacy of Lily Briscoe. It’s a moment that captures both the burden he places on others and his desperate longing for significance. Mrs Ramsay, meanwhile, is drawn with luminous tenderness. Charles Tansley thinks of her “she was the most beautiful person he had ever seen” and the children are entirely dependent on her. She offers the understanding the young male students of her husband need, knits a stocking for the lighthouse keeper’s son and smooths over tense moments at dinner. In these scenes, Woolf recreates her mother’s presence and captures both her timelessness and her passing.

writing and painting the past

Reading To the Lighthouse it’s impossible not to think of Vanessa Bell, Virginia’s painter sister, and her art. Virginia and her older sister were the “Stephen girls”, who, after the death of their mother, were left in the care of their older brothers, George and Gerald, as Victorian society dictated. Vanessa, like Stella, was raised to be a perfect Victorian lady who was supposed to take her mother’s place and care for her father and the house. But that didn’t happen. She took the path of art and, after their father’s death she moved to Bloomsbury together with Virginia and their Stephen brothers, Thoby and Adrian, and together they founded a community of artists.

There is no direct correspondent in the book for Vanessa, as there is for Julia and Leslie. Lily is a painter, but while her art does reflect Vanessa’s art, she fights, like Virginia, to make her voice be heard and her vision come to life. Lily’s art is part of a movements which is a departure from what was recognized as art at the beginning of the 20th century. Woolf allows women to take the centre stage in the development of painting, while a certain Mr Paunceforte, respected as he might be, is made a mock out of.

But her grandmother’s friend, she said, glancing discreetly as they passed, took the greatest pains; first they mixed their own colours, and then the ground them, and then they put damp cloths on them to keep them moist.

Lily paints what she sees and what she feels, but that’s different from what people expect her to see and feel. Her doubt is constant, yet so is her persistence. Lily begins the painting of Mrs Ramsay and James sitting in the window in the first part of the novel, but her work is interrupted. It is only 10 years later, when James and Cam, now young adults, return to the vacation house on the Isle of Skye, together with their father and Lily, does Lily’s understanding of Mrs Ramsay and the past allows her to place the final brush stroke on her painting. Lily’s struggle with her art and with the passing of time is Woolf’s too. Only when they’re both 44 years old can they find a form that holds ambiguity, memory, and the invisible threads that bind people together. Virginia Woolf by writing To the Lighthouse and Lily Briscoe by finishing her painting.

Beautiful and bright it should be on the surface, feathery and evanescent, one colour melting into another like the colours on a butterfly’s wing; but beneath the fabric must be clamped together with bolts of iron

I really love how painting and writing come together in the art of Lily Briscoe. I feel that by combining the two forms of art Woolf says something more than any of them could express alone. Painting gives shape to the unspoken, while writing gives the feeling of time passing. Together they echo the inner workings of memory – blurred, layered, in continuous making and remaking. Lily’s final brush stroke feels like the final sentence Virginia Woolf wrote for To the Lighthouse – tentative, but true, not a resolution, but a gesture of faith in the act of creation.

Yes, she thought, laying down her brush in extreme fatigue, I have had my vision.

I wrote this post in preparation for the Literature Cambridge 2025 Virginia Woolf summer school. The series of lectures and seminars focused on life writing in five of Woolf’s works.

References

Hermione Lee Virginia Woolf, Chatto & Windus Ltd., 1996

Katherine Hill-Miller, From the Lighthouse to Monk’s House – A Guide to Virginia Woolf’s Literary Landscapes, Duckworth, 2001

Marion Dell and Marion Whybrow Virginia Woolf & Vanessa Bell – Remembering St. Ives, Tabb House, 2004

your thoughts?