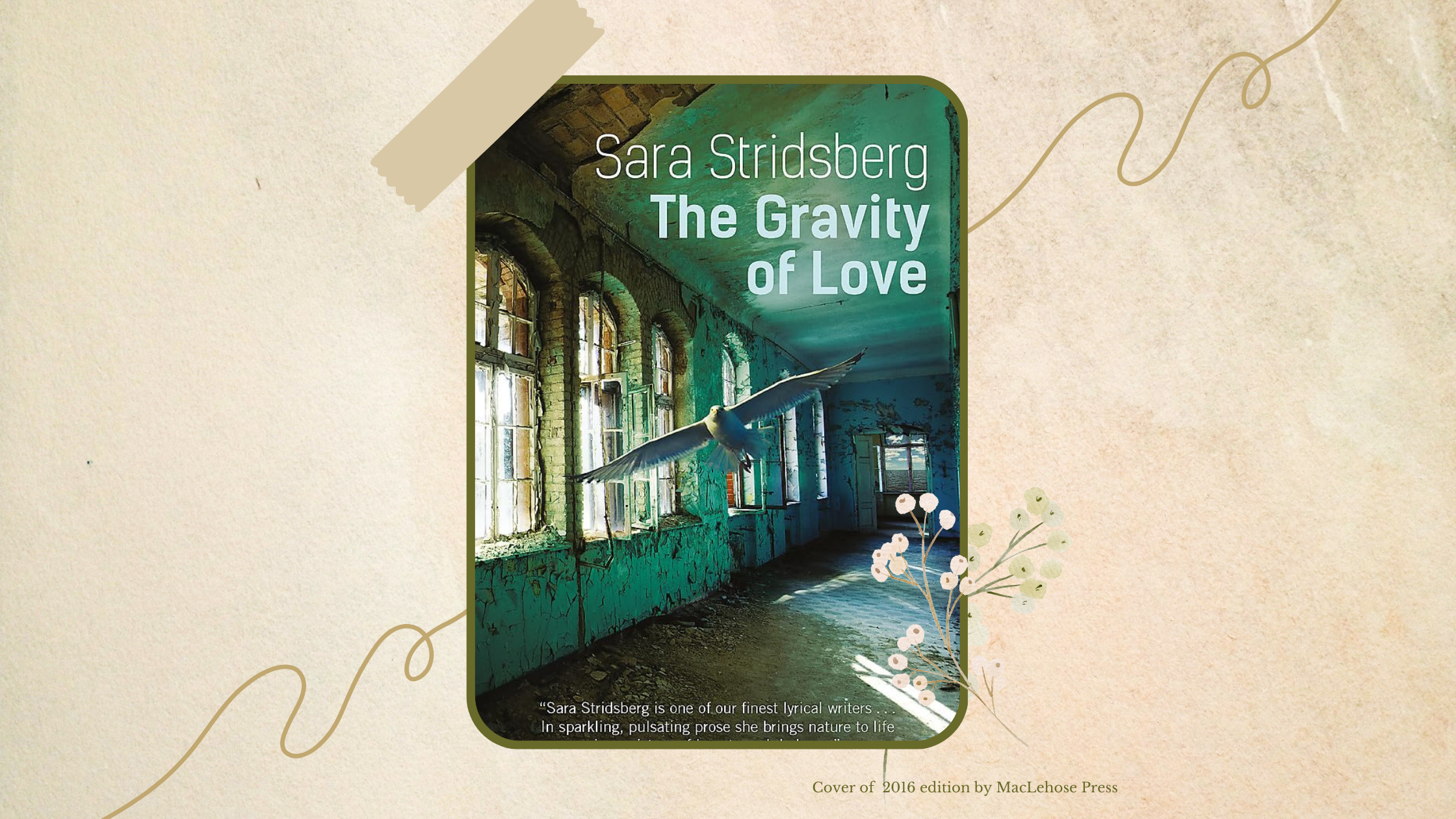

I literally never listen to music while reading. It distracts me, I feel it’s pulling me away from the rhythm of the language and it shuts down the silence between the lines. Yet reading The Gravity of Love by Sara Stridsberg to the sound of modern piano compositions was one of the most fulfilling literary experiences I’ve ever had. Because you can’t just read the Swedish writer’s novel. If you do just that, you’ve missed 90% of the point. The story moves through images, sensations, and fragments of thought that blur the line between memory and dream. You really need to feel it, to immerse yourself in the intensity of her images of Beckomberga, the mental institution which takes most of the story, and let her sensorial writing reach all your senses. Words don’t quite work when trying to describe her writing. You might understand better if you listen to a Yann Tiersen piano concert and feel that beauty and melancholy which slips in and out of the possibility of expression.

the story of the gravity of love

The Gravity of Love tells two stories. First, it’s the story of a broken family from the point of view of the daughter, Jackie. Second, it’s the story of Beckomberga, Sweden’s probably most well-known mental instution. Because of alcoholism, Jim, Jackie’s father, is committed to Beckomberga. Lone, her mother, is absent-minded, sinked in her own interests. The novel jumps in and out of Jackie’s story, as she tries to piece together a life from the fragments her parents left behind. She is only 14 as she visits Jim often at Beckomberga, and the place becomes her second home, a place of both sadness and wonder, filled with characters who, like her father, seem to hover on the edge of living. Edvard Winterson is the doctor in charge of the patients, Inger Vogel is the nurse, and Olof and Sabina are two other patients, each carrying their own sadness and their own loneliness.

No one has ever believed Jim would become old. He has always stood beyond the bounds of time and lived according to his own rules, like an overgrown child, dangerous and unruly, and he has always liked death too much for anyone to imagine him in his dotage. I do not think he has ever loved anyone. Not me, or my half-brothers, perhaps not even Lone.

Time shifts by its own rules in the novel, and somehow, the characters do too. At the beginning you don’t really realize who’s who and, as a first-time reader, the sensory experience of the writing takes most of the impression the reading leaves behind. But when you start piecing things together, you realize Jackie is a mother herself, raising her son on her own after breaking up with her partner. There’s a twenty-year distance between her and Jim, a space filled out by family photographs, stories of the past and the memory of the days visiting at Beckomberga. Jackie sinks deep in each photograph and each memory, no sensation escapes her capacity to revive the past.

beckomberga

Sara Stridsberg based her Beckomberga on the real institution of the same name, which was open between 1932 and 1995. Her own father had also been hospitalized there, though she’s said the novel isn’t autobiographical. Still, the emotional undercurrents of the novel flow with such clarity, that it feels like it could only have come from lived experience. Under Stridsberg’s pen, Beckomberga sheds the outside layer everyone could very well image – a place of desperation and strange medical practices. The hospital becomes instead a refuge for the unloved, the unmissed and the lonely.

Historically, Beckomberga was one of Europe’s largest mental hospitals, with room for up to 1600 patients. It was shut down in 1995 as part of Sweden’s deinstitutionalization wave, following criticism of large-scale psychiatric hospitals. In the novel, the place borrows from its real-life twin, and Stridsberg doesn’t shy away from weaving reimagined history in her writing. Her Beckomberga is very physical, its hallways ringing with the sounds of life and its gardens filled with light reflected in the eyes and lives of those living between its walls.

We wait for Jim in one of the corridors. The walls are green like the inside of a pool, and a square of light comes out of every room. The sound of voices in the distance, a solitary black fly crawling along the wall.

sensorial reading

Over the course of the novel Jackie switches between present and past, between the present tense of the telling and a past tense of heartache. But that’s just one of the ways the story carries its weight. Another way is how it absorbs the world it creates. The sentences, just words on a page, hold texture. They are heavy with color, scent, motion. They create a very material blanket which you can touch and sink yourself in.

She turns and looks at me. The intensity in her eyes makes me almost back away. In the distance is the sound of an aeroplane taking off from the airport and darkness is rapidly falling around us, as if someone has thrown a blanket over the sun.

The Gravity of Love, and generally, Swedish literature, has widened my readerly horizons. It made me more aware of rhythm, of the music of words and of the materiality of the atmosphere. Reading it reminded me that literature is not just about the feeling in the mind, but also about the material body it leaves behind.

your thoughts?