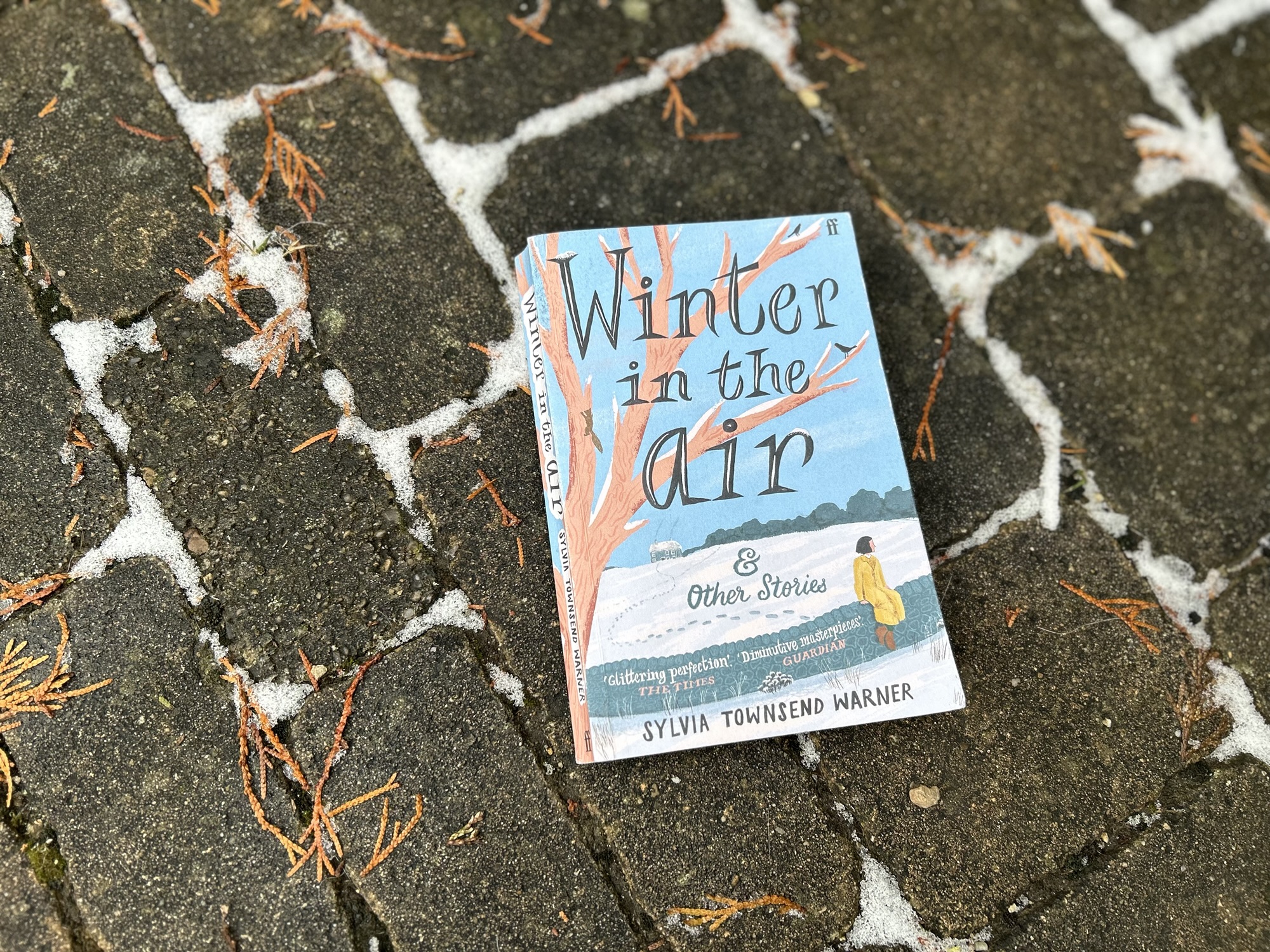

I instantaneously fell in love with Sylvia Townsend Warner’s writing when reading her collection of unpublished short stories, The Music at Long Verney. Rereading what I wrote back then, I can still remember how her choice of subject, her twists and her portrayal of characters (especially Mr Edom and his customers) enchanted and delighted me. As I picked up her 1938 collection, Winter in the Air & Other Stories, it was only natural that I was expecting to revisit those old feelings. I did, in some ways, but in many other ways I think I only now discovered the real Sylvia Townsend Warner. The stories in this collection feel colder, more sober, drenched in second thoughts and in a general sense of chill and doubt which floats in the fictional air. They all have ordinary lives and ordinary days at their center, and maybe that’s why they leave the reader trying to catch that ineffable something which exists in all human relationships.

The title of the collection is mind-blowingly well chosen. Winter is indeed in the air as a promise of season, but also as a metaphor of a very particular existential state. Winter means growing old and growing apart, and it also suggests a deadening stagnation, a moment which can last for months and years and which recognizes no stir of life. Looking back with the knowledge gained by having read the collection, the opening story, also titled ‘Winter in the Air’ is a perfect palate-tickler for what we can expect. Barbara is moving to an apartment in London and is thinking back on the relationship with her now former husband and how they came to separate. They are on good terms and she’s writing him a letter, telling him that she arrived well. Yet words soon run out on her and she can only think of a verse in The Winter’s Tale: “your favour I do give lost, for I do feel it gone”. Everything else can only be guessed hanging in the chilly air of the room.

One of the most striking aspects of the stories in Winter in the Air is the exploration of the relationships between men and women. Townsend Warner perfectly captures the grey nuances of romantic and domestic entanglements with a much-welcomed tinge of humour and soft irony. In many stories, the dynamics between husbands and wives, lovers, family members are marked by unspoken tensions and small betrayals, which feel almost like nothing. But if they are nothing, why write a short story about it? In ‘At the Trafalgar Bakery” a young woman runs away with her lover, but his being delayed at their point of rendezvous gives her the opportunity to pour out her soul to a cat. In ‘A Kitchen Knife’ social expectations placed on a young wife are not subtle at all. So much so, that, in an attempt at rebellion, she steals her friend’s “real, old-fashioned kitchen knife”. These stories will offer no answers to the ambiguities of human connections. But they will leave you wondering.

hee-haw!

It was as though the fog were billowing past, dry as smoke, between her and the old man with his stumbling attempts at the courtesies of farewell. Absorbed in her bitter melancholy, she did not notice when he went away.

‘Hee-Haw!’ was my absolute favourite of the collection, because it asks a question which I often ask myself – what truths, which remain hidden to us, do other people know about us? Mrs Vincent returns to the village where she and her previous husband spent years of their marriage. Their marriage ended badly, and she left the village, while the husband continued to live there and be a beloved painter. Nobody recognizes Mrs Vincent, for she returns under the disguise of a new name and a new look. But when she starts talking to an old man over tea, she realizes that it’s she who doesn’t recognize herself in the stories the old man tells.

Even though the story is barely 10 pages long, I barely scratched the surface with my summary. There is so much happening in the back of Mrs Vincent’s mind and so much which we don’t have access to. Occurrences from her marriage are barely hinted at, not to mention it’s never clear why she returns to the village of her marriage in the first place. The picture she has of herself and of the village changes of the course of the story. At first, she recognizes the sounds and the streets, but when she starts talking to the old man over tea, the focus changes. The ending is a bit predictable, but the ambiguity remains – who got it wrong in their marriage? Was it she? Was is her husband? How much do appearances make up the truth?

under new management

‘She’s dead.’ ‘Dead!’ said the accused man incredulously. ‘Do you mean it? Dead? Christ, what a swindle!’ He burst into furious laughter, and the lawyer averted his eyes from a client he already deplored.

I loved this short story because it’s a roller coaster of emotion and facts which shape the reading experience. It starts at the end, with the main character, Miss St John, already dead, and a young man charged with murder strangely pleased at the news. The story turns then back the beginning, where we learn that elderly Miss St John was a permanent resident in a shabby hotel called Peacock Hotel. She takes pride in her statute, but she finds herself in need to adapt her well-established habits when the son of the owners returns home and is said to take over the ownership of the building. The story has a twisted sense of humour in how the relationship between Miss John and Dennis, the future owner, is portrayed. They clearly dislike each other, and each one has their reasons. We only learn Miss John’s point of view and follow her as she makes her way across the town in search of a new place to live. Her journey is tinged with what seem like insignificant encounters, but which in the end weigh a lot in the picture we make of her.

absalom, my son

The coffee pot was on the stove, it only needed heating. This time, instead of leaving it to boil, boil over, and boil away, he remained in the kitchen. One of Loveday’s lending library books was on the window-sill. Without looking at the title, he opened it at random and read on till the coffee boiled.

It was hard to decide if my second-favourite story was ‘Absalom, My Son’ or ‘Under New Management’, so I will just award both of them the silver medal. ‘Absalom, My Son’ is more conventionally satirical that ‘Under New Management’, and picks up again the idea of what other people go through which we have little idea of. Mr Bateman is a moderately successful elderly writer who looks for a new house to rent when his old house burnt down. His assistant, Miss Loveday, helps him in the search and also lives in the house to help the famous author with typing and other things which women are obviously and generally good at – such as boiling coffee and tea and keeping the kitchen. Miss Loveday spends her time otherwise reading books from the library, which Mr Bateman, in his wisdom and writerly experience, doesn’t think much of. But when he finds himself on a writing block and turns Miss Loveday away from the house for some days, it is precisely in a library book where he finds much needed inspiration. I liked the story because I had a good laugh at Mr Bateman, but I could also see that he’s just an old man over whom the waves of new times wash over.

your thoughts?