I just want to admit straight away – I am not familiar at all with Italian literature. I read Alba de Céspedes’s masterpiece, Forbidden Notebook, because it was lying around the house of my great-aunt when I was younger and recently started reading Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Tetralogy because my book club at work voted for it. It’s sometimes scary how you stumble upon great literature. Yet reading these two great Italian authors made me hungry for more, and Italian short stories are what came in handy.

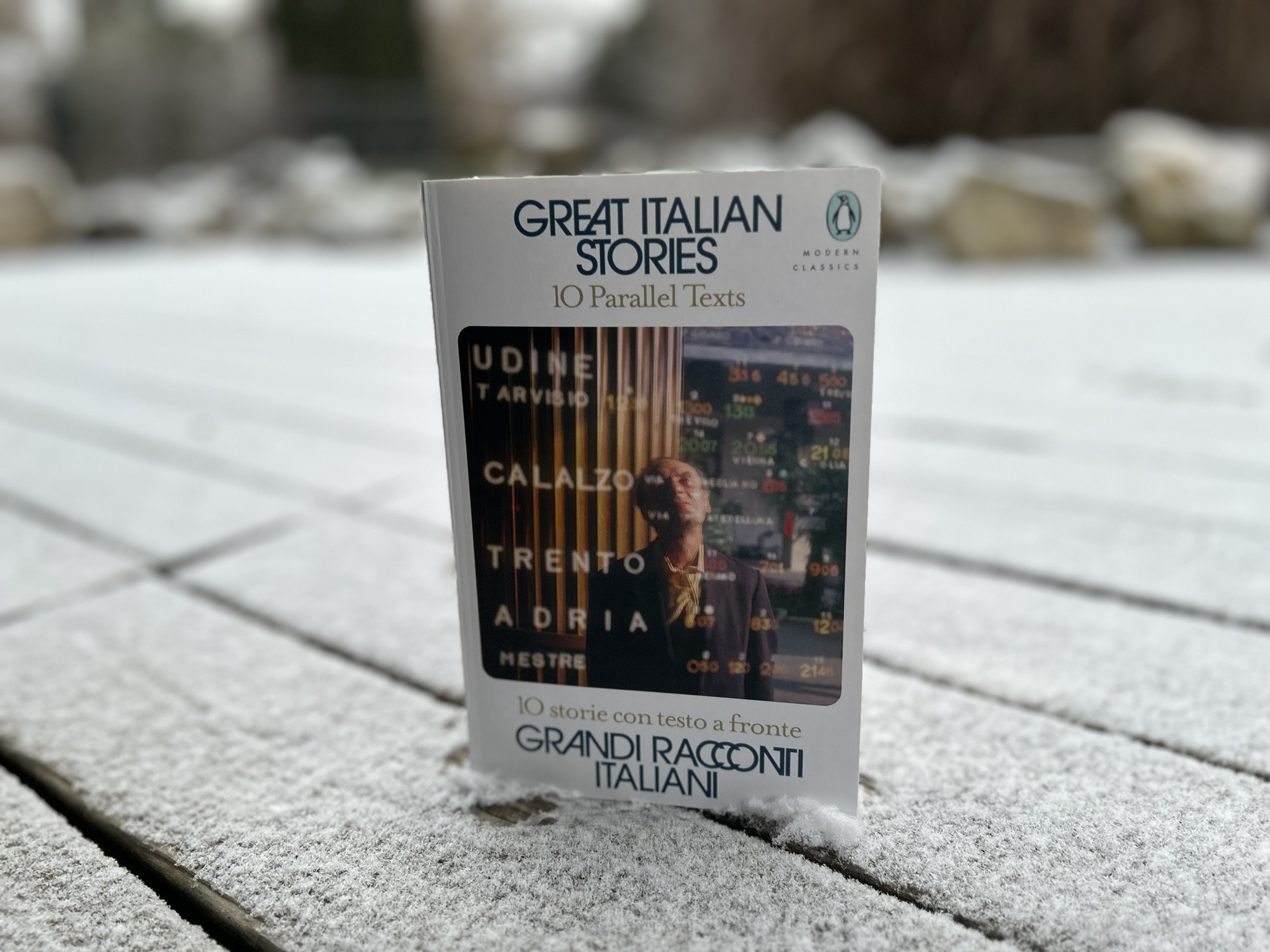

A while ago, Penguin published their anthology of Italian short stories, and some years later they made another selection. 10 bestest short stories, published in a dual-language edition: Italian original and English translation. It is a treasure for readers who are learning Italian and for readers like me who would just like to get the feeling of how a great short story sounds in the original words it was written. All 10 authors published here are huge names of Italian literature, among them Strega Prize and Nobel Prize winners, such as Italo Calvino, Natalia Ginzburg and Grazia Deledda. The collection is useful as a starting point to continue exploring these writers, but also to just enjoy the best Itay has to offer in terms of short story writing.

natalia ginzburg ‘my husband’ (1941)

Could be a bit early to say, because I still have a lot of European literature to read this year, but Natalia Ginzburg might very well be the discovery of the year for me. Ginzburg and her first husband, Leone, were strong opponents of the Fascist regime and they edited together an anti-Fascist newspaper in Rome. Leone was imprisoned and died under harsh torture. Natalia went on to become a prolific writer, with her work being published by the prestigious Italian publishing house Einaudi. She wrote several novels, but only 8 short stories, which were only recently translated for English-speaking readers. Her most famous short story must be ‘The Mother’, which looks at the life of a young mother from the perspective of her children.

‘My Husband’ is an early short story, nevertheless wonderful, and surprising, to read. The story is told by an unnamed female narrator who tells us straight off the bat: “I was twenty-five years old when I got married”. She marries a thirty-seven-year-old rich man, but not out of love. After meeting a few times, the man asks her to be his wife, and she accepts. We only learn later what lies behind this: by marriage, her husband tried to escape from an obsession with a young woman in the village, Mariuccia. It is heartbreaking to read how he confesses to his wife, all the while she is doing everything which was expected of her – household, social visits, having children. And she barely stands up to her husband’s passionate confession. All her feelings are bottled up, and only, we, the readers, are subtly made aware of them.

Books always leave more to uncover. Subscribe to get more reflections and interpretations delivered by email.

alba de céspedes ‘invitation to dinner’ (1955)

Alba de Céspedes seems to enjoy a revival over the last couple of years, with several of her novels being reedited in Europe. She was jailed for her anti-fascist activity in the years leading up to WWII, and two of her novels, Nessuno Torna Indietro (1938) and La Fuga (1940) were banned. Her revival coincides with my rediscovery of her probably best-known novel, Forbidden Notebook, which I have just recently reread, and which her short story ‘Invitation to Dinner’ subtly echoes.

I can’t possibly make sweeping statements about de Céspedes’s work, but these two fictions I read by her do draw some guiding lines. She writes of the years after the war, how Italian society becomes aware of changes, a’nd how women come to terms with the new social situation. And all this nicely packed in a story which leaves you pondering. The short story is told from the point of view of an Italian wife. “The story I am about to tell concerns an event that is not very important in itself”, she warns the reader. She and her husband invite a British officer to dinner, to say thank you for having helped the husband’s brother to return to Rome after the war. Over the course of the dinner, the discussion turns political and the British officer is keen on displaying his knowledge of “Italians”. “You have to work hard and demonstrate through your politics, through your civilization, that you’re a people who deserve to be helped”, he arrogantly advises the family. The dissonance between the woman’s pride as Italian and as wife, and her status as a host, is what gives the story richness and body.

fausta cialente ‘malpasso’ (1976)

‘Malpasso’ is a delicious gem of literary irony, which plays on the expectations and stereotypes surrounding men and women. An unnamed old man, who over the course of the story is nicknamed The Professor, spends some weeks in winter in a vacation resort called Malpasso. At first, he keeps to himself, but slowly he starts talking to patrons in the main restaurant of the small vacation village. He soon starts telling others about his wife. “It was simply an impossible life, years of never being able to swallow a bite of food in peace with that ugly, poisonous, aggressive woman around”. But when somebody asks The Professor why he married the woman, his story changes. His wife is dead, he says, and before that, she had been sick, and the sickness had changed her. When he first married her “she had been a darling woman, a sweet, beautiful bride”. The patrons’ interest increases, and “this beautiful ghost reigned over the Malpasso clientele for some time”. I highly recommend to seek out the story and find out by yourself the truth behind the old man’s story. High literary entertainment is guaranteed.

grazia deledda ‘the hind’ (around 1910)

‘The Hind’ revolves around Baldassare Mulas, an old man whose daughter died in the wake of a social scandal, and his servant, Malafazza. The old man retreats from society and spends time in the woods and in the company of animals. The story is told in bits and pieces by Malafazza, who bad-mouths his master to the cattle dealer. Mulas slowly starts befriending a young hind to the point that he treasures her more over any other human being. Sardinia is recurring in Grazia Deledda’s work, and we might well assume this is where the story is taking place. The woods and the wildness of the landscape make up for the atmosphere of the story and they are almost a character in themselves. It would be easy to make a symbol out of the hind, but it is just so beautiful to enjoy the pure presence of nature and the friendship which blossoms between nature and human being.

your thoughts?