Halloween and horror. A match made in heaven. Or, rather, hell? So of course there is no better night of the year to enjoy some classic horror which gives you the goosebumps, but also makes you ask the hard questions. Horror might have at one point started with ghoulish folktales told by the fire for the pure scare of it, but the 19th century masters poured their imagination into dark fictions of ambition, isolation and madness. Horror became a platform to explore the consequences of humans overreaching mental, physical and natural boundaries.

Writers like Mary Shelley, Edgar Allan Poe, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman wrote tales that were as much about monstrous figures as they were about the inner demons of their characters. Their stories ask: What happens when the creator loses control over their creation? Can the product of one’s mind or hands ever be greater—or more dangerous—than its maker? The pursuit of these questions gave rise to some of the most classic of classic works of horror, guaranteed to summon up dark questions in the dark night of Halloween.

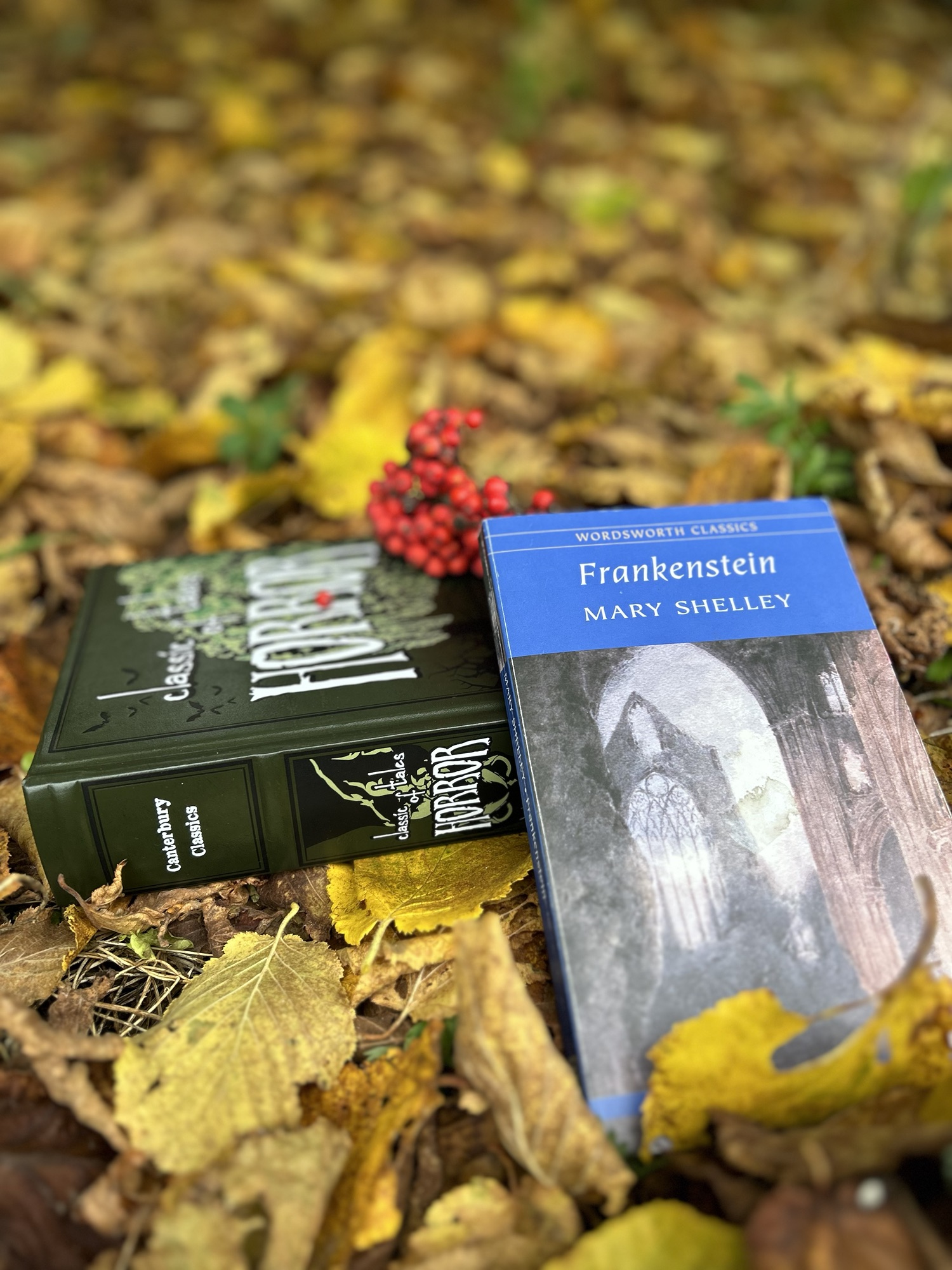

mary shelley’s frankenstein: creature and creation

I can’t tire of stating the fact: Mary Shelley started writing Frankenstein, her first novel, at the age of 18, and published it in 1818, when she was 20. Even at that age, she seemed to know so much about ambition, failure and rejection. The story is about Victor Frankenstein, a not-so-ideal scientist and his experiments with life and death. The reason for his experiments is not grounded in objectivity, and his base human traits gain the upper hand. He is blinded by pride and greed, has no sense of responsibility and cannot deal with the consequences of his actions. His problem is not that things did not go as planned but that they did. “These luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes … his shrivelled complexion and his straight black lips”, he says about his creation. It’s almost as if he had forgotten that he put the creature together using lifeless body parts, bound to inspire fear and rejection. He wanted to create life, and in blindly pursuing his purpose, he hid from the fact that he started from death. And when he does see death come to life, the veil he hid behind falls.

Maybe it’s not that Frankenstein deserted his creature, nor the creature’s unnatural figure, that led to his turning into a “daemon” and a “wretch”. Maybe it’s the flaws of Frankenstein which transferred, distortedly, onto his creation. Like his maker, the creature has “powers of eloquence and persuasion.” But the disaster happens when he comes into direct contact with people, who don’t and can’t see beyond his physical appearance. The creature learns rejection more than once but can’t simply accept it. He turns it into murder and cruelty. He becomes a distorted mirror of Frankenstein and his world.

Yet it’s not so simple. There is a surprising twist in the relationship between Frankenstein and his creature. At the end of the novel, the creature takes complete control over his makes. As he did before, Frankenstein takes no responsibility for the deeds of his creature and swears revenge, tracking him across the globe. But it is the creature who controls this game. He lets himself be seen and leaves food and messages for his pursuer to make sure he stays in the game. This shows cunning and determination, none of which the reader sees the creature learning or experiencing. This is an unexpected outcome, untraceable and unexplainable.

e.a. poe’s ‘the fall of the house of usher’: decaying creation, decaying creator

The act of creation and its consequences reach mad intensity in Edgar Allan Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher. Like pretty much all of Poe’s short stories, this one unfolds in the mind of the reader with time. Even though it’s not extremely long (15 pages in my small-print hardcover collection of 19th-century classic horror) it requires a lot of mental work from the reader. The story is told by an unnamed narrator who visits his friend, Roderick Usher, at his decaying family home. Usher is sick with a mysterious malady and his sister and only family left alive, is fading away.

The Usher mansion is both a physical space and the physical presence of Usher himself. Anything but a home. Horror has the delicious capacity to take that which is dear and safe and reveal its dark side. Roderick, with his artistic obsessions and morbid sensitivity, creates an atmosphere that becomes increasingly suffocating and fatal.

Dark draperies hung upon the walls. The general furniture was profuse, comfortless, antique and tattered. Many books and musical instruments lay scattered about but failed to give any vitality to the scene. I felt that I breathed an atmosphere of sorrow.

The eventual collapse of the house makes also for the inevitable death of its master. In the story, the creation – the house and the suffocating, supernatural atmosphere – consumes its creator. Just as Frankenstein’s creature learns from its maker’s fatal flaws, the house mirrors Roderick’s fractured psyche. When creator and creation are bound so tightly, destruction is inevitable.

charlotte perkins gilman’s ‘the yellow wallpaper’: repression and creation

‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ by Charlotte Perkins Gilman is, I think, a sort of scramble of Frankenstein and ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’. The unnamed narrator has no literal creature of her own, though. It is her mind which opens the gates to psychological creation, forming a reality of its own. Gilman was a feminist and an advocate for women’s rights and her work was primarily focused on the inequality of the genders. The author stays true to her beliefs in ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’, but the horror of the short story is unique in Gilman’s oeuvre.

The story is told in diary-like form by a woman who, because she suffers from an unclear sickness, has been recommended bed rest by her controlling and patronizing husband. The woman begins to be more and more obsessed with the wallpaper in the bedroom and begins to see a woman creeping behind the pattern and then leaving the wallpaper for the room and the gardens. This woman is not just a creation of the narrator’s mind but a projection of her entrapment. In trying to break free, the narrator’s creation – a creeping, imprisoned version of her psyche – overtakes her own identity. Here, too, the question arises: is the creation a mirror of the creator? Or the true reflection of the original, but distorted through suffering and repression?

As a reader, there’s always the question of whom you identify with. When looking at myself from the outside and wondering what steps I took to bring myself where I am now, I do feel a bit like Frankenstein’s creature. I feel like people have left their marks on me, but I also feel that my mistakes are mine to make. If I was an experiment, there’s no repeating me. This sense of being both the creator and the creation echoes in the horror fiction I’ve read this Halloween. Like Roderick Usher, I am sometimes trapped by an environment of my own making, haunted by the boundaries I set for myself. And like the narrator of Gilman’s story, there are times when the creations of my mind—the stories, fears, and ambitions—threaten to break free and take on lives of their own.

Yet, for any present or future creations, there is always a variable that can change, a frame that can shift. The house can decay, the creeping figure can emerge, and the creature can claim its independence. But how much better than their creators can the creations be?

your thoughts?