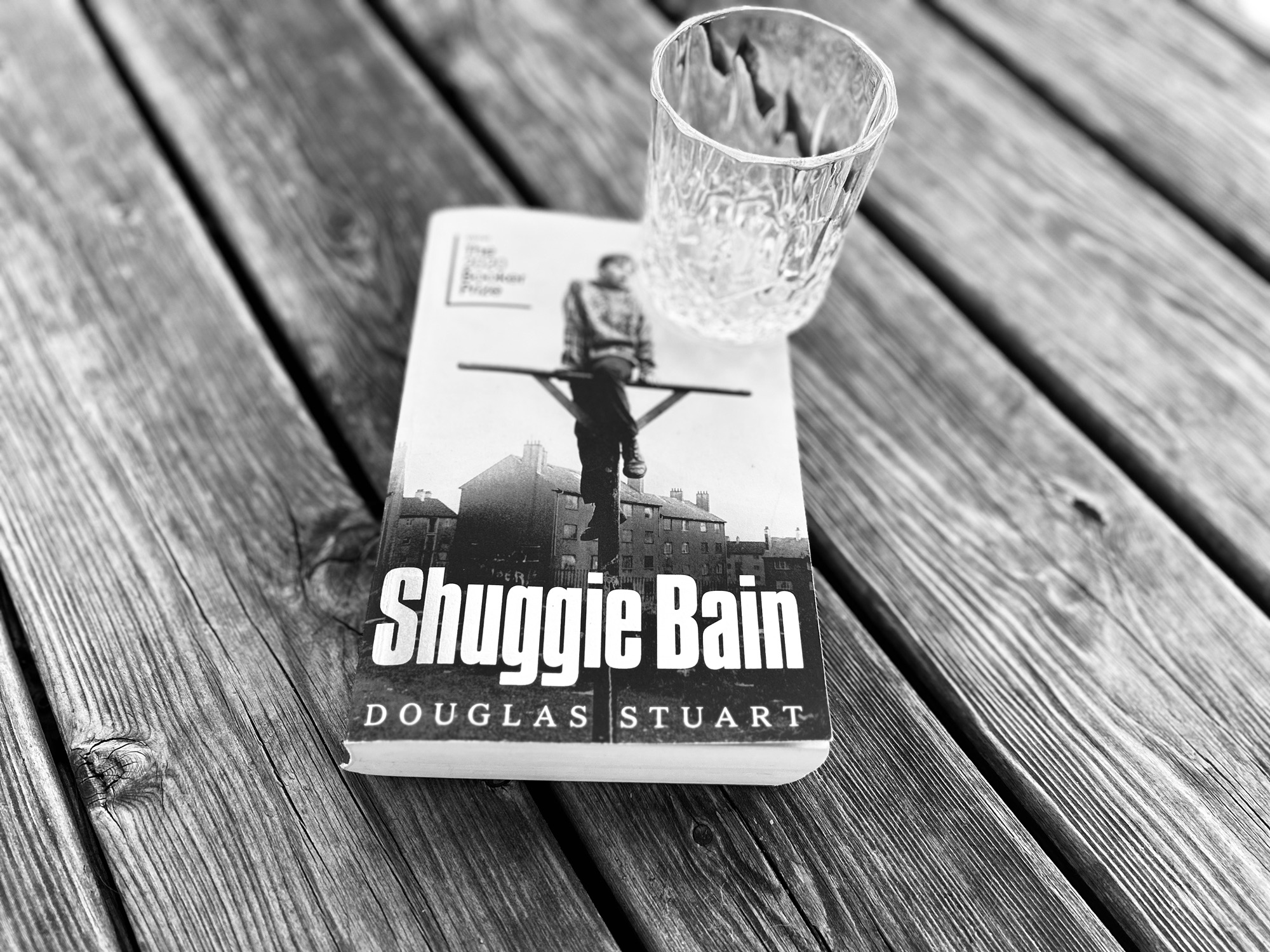

In the autumn of 2023 I went out with a friend to a new Thai place in the city. It was raining and I could barely find the restaurant on a side street, next to a hotel flashing its brand name in the otherwise dark alley. We barely sat down and put our umbrellas to the side when my friend pulled out a book and set it down in front of me. I knew the book, of course, she had been raving about it for the past 3 years since Shuggie Bain got the Booker Prize. I had watched Youtube videos and a live online discussion with Douglas Stewart in Munich. But I never expected for the book to meet me on a November evening in a Thai place of all places. But that’s how it goes. I promised my friend I would finally read the book this year, then we moved on to ordering drinks and getting a bit warm.

the story

Douglas Stewart’s story is not one-of-a-kind. In 2002, Elena Ferrante wrote in Days of Abandonment about a mother breaking down mentally and emotionally after her husband leaves her for another woman. In 1999 Jacqueline Wilson’s The Illustrated Mum, a children’s novel, depicted a bipolar mother and her young daughters who have different ways of dealing with their mother’s moods and self-destructive behaviour. What is special about Shuggie Bain and sets it apart from similar stories is the gut-wrenching relationship between the young boy Shuggie and his mother Agnes.

The story follows the life of Shuggie Bain, a boy growing up in the poor areas of Glasgow, and his relationship with his mother. Agnes is a beautiful woman with dreams of a better life for her and her three children, but she’s trapped by poverty and, worse, by alcoholism. Her addiction is the central force of her life, and tears apart her relationship to her parents and her children. Shuggie is the youngest of the three children, the son of violent Big Shug, and the one who is most desperate to save his mother and care for her, even as she sinks deeper and deeper into her bottles of vodka and cans of lager. Touching scenes pour in almost at every turn, and you almost can’t tell where the borders are, where motherly love ceases and smokes off in the bitter flavour of warm lager. In one scene at the beginning, Shuggie is a 5-year-old who tries to keep his mother happy just before his heavy-handed father comes home for a tea break. “He did whatever had caused her to laugh another dozen times till her smile stretched thin and false, and then he searched for the next move that would make her happy”

the darkness

The novel is drenched in darkness and is definitely not an easy read. The story, set in the Glasgow of the 1980s draws on a bleak setting – rampant unemployment, working-class families fighting to make ends meet, a grim landscape of a Glasgow in decline which is unforgiving to its young and vulnerable. Closed coal mines and dilapidated council estates form the backdrop of Shuggie’s life, whose single glimpses of short-lived happiness are a warm bath and the hope to see his mother released from the demon of drink.

But the darkness in Shuggie Bain is not confined to the surface. It crams into the small spaces between people close to each other, embraces their bodies and engulfs their hearts. Agnes’s older two children are slowly driven away as she sinks deeper into alcoholism. Catherine marries off and moves to a different part of the world even and Leek, who prefers to spend as much time away as possible, dreaming of and saving up for art school, is kicked out of home by Agnes herself. There is much discomfort around matters of the body, as well. Agnes and Leek have false porcelain teeth and the author misses no opportunity to push his camera as close to the mouths and bodies of the characters, deformed by old age, alcohol, and harsh life. “The discomfort of false teeth was nothing when compared to the movie star smile she thought they must give her. Each tooth was broad and even and straight as Elizabeth Taylor’s.”

the women

Reading online reviews, there’s much criticism for the book. Some argue that there is no redemption for the characters, everyone is predatory towards everyone else, there is no sense of sticking together, even between neighbours who share the same fate of poverty. I feel the same, especially when looking at how women are portrayed. I didn’t expect the book to be a Scottish My Brilliant Friend but offering really nothing to the reader in way of decent human beings? Nothing to Agnes in way of a friendly hand of support?

In a scene at the beginning, Agnes’s friends gather at her house to play cards. Agnes’s mother, Lizzie is also present. But I didn’t get the sense there is anything connecting them. They are, of course, described in visceral tones. They have “greasy fingers”, they “cackle”, they “fight over a few pounds in copper coins”. They spend some hours together as a break from house chores, offering marital wisdom to each other, regretting the loss of the youth in their bodies. As a reader I felt they were there to make a point. Reeny turns out to be Big Shug’s lover and Nan cheats, ripping off the other players for her own Sunday stew. Neither of them ever shows up again, but we are left with the clear feeling that nobody is there for no one.

Thinking back at how the book landed in my hands, it couldn’t have been more fitting. A dark rainy night in a dark alley. Could have almost been a scene in the book. Almost. I can’t compare my innocent evening out with the dark alleys of Glasgow in the 80s, populated by predatory taxi drivers and young girls stumbling out of late-night bars. It’s useless to say the book doesn’t offer a fairy-tale happy end. But in some way, the grit of the city is defeated, even if just in the form of Shuggie’s memories of his mother and his childhood.

your thoughts?