I remember being in school and the teacher giving everyone an assignment in class. We were to draw a big square and divide it into four little squares. In the first square we were to make a drawing of ourselves as we see ourselves. In the second square, a drawing of ourselves as we assume other people see us. In the third square, a drawing of how we would like to be seen. And in the fourth, what changes we are willing to make for that. I didn’t think much of it back then. I think I drew some random stick people, as drawing never was my strong suit. Too bad we didn’t get the assignment to write an essay in each of the four squares.

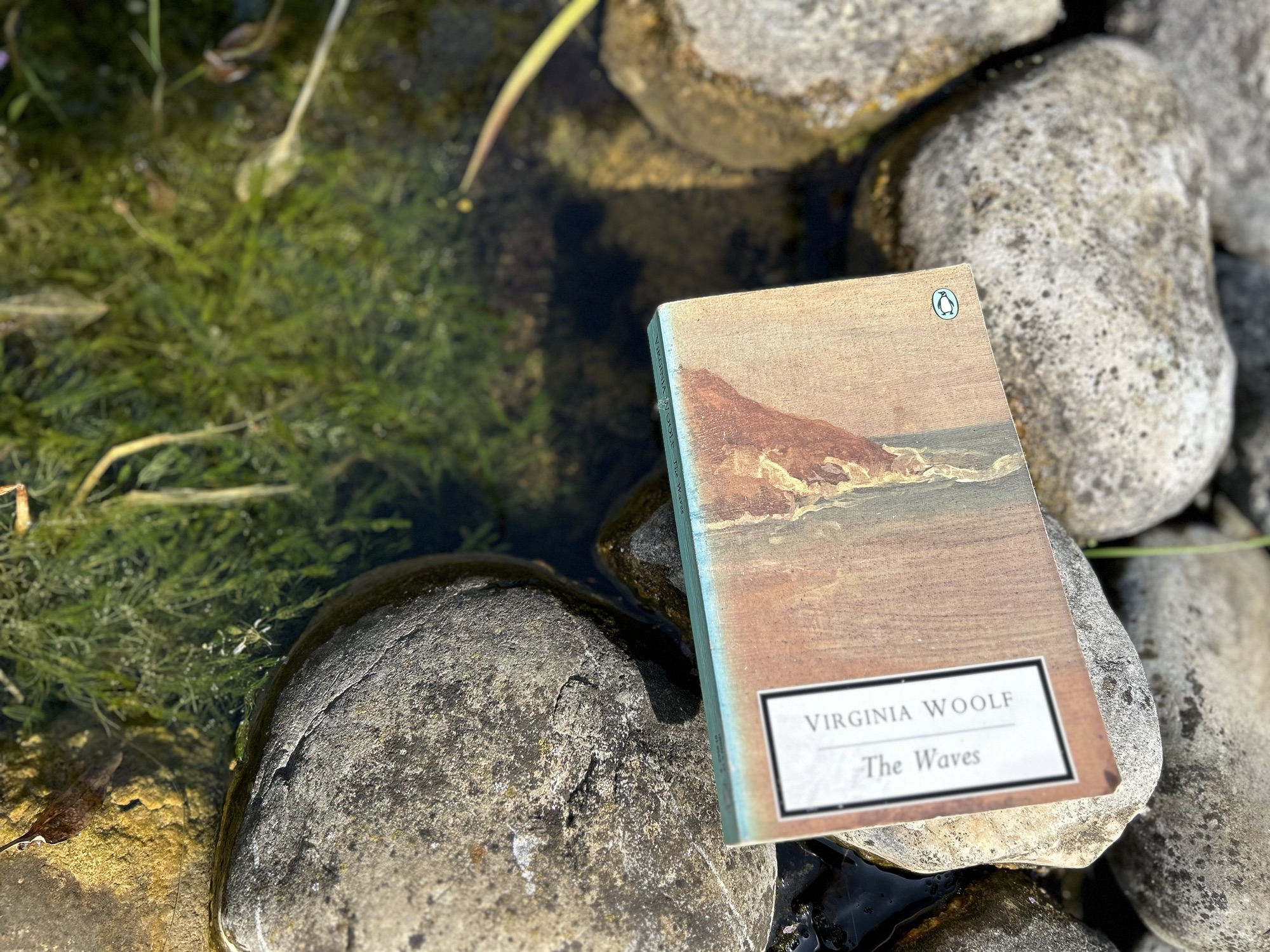

I had forgotten about this moment until starting to read Virginia Woolf’s 1931 novel, The Waves. The book was a long time coming. I kept telling myself I would read it when I’m prepared for it, I thought I was prepared for it, but the truth is nothing can prepare you for the washing machine cycle that is The Waves. The book starts with 6 sentences seemingly spoken out loud by 6 main characters who, as the story continues, sink and rise above the rich liquidity of the “narrative” (?). It’s so hard to use conventional words to express my thoughts about the book! Novel, narrative, character, story. The Waves falls under all these words, yet soars above them, leaving them behind, all meaning sucked out of them.

the (very) short of the waves

The novel follows the lives of six characters. Bernard, Susan, Rhoda, Neville, Jinny and Louis grow up together, go to separate schools, as dictated by their gender, and live in London. They are brought together by their friend, Percival, a ghost character. He has no voice to tell his story, and all we get about him are glimpses of subjectivity mirrored off by the six friends. The novel itself follows no traditional linear structure. The reader gets the impression of a dialogue because of the many “said Bernard” and “said Susan”, but what they speak are a series of soliloquies, where they reflect on the passage of time, on relationships, on each other, and generally on just living in the world. They do speak to each other in a way, but more to themselves.

‘I see the beetle,’ said Susan. ‘It is black, I see; it is green, I see; I am tied down with single words. But you wander off; you slip away; you rise up higher, with words and words in phrases.

The narrator is an elusive presence in the book, even more so than Percival. She only tells us who says what, and that’s pretty much it. Unless, of course, we consider the short narrative interludes which describe imagery devoid of the human presence: the sea, the sun, birds, a house in which nobody lives. They appear at the beginning of each of the novel’s nine sections and, to be perfectly honest, they seem quite detached from the rest of the book on a first reading. It’s almost as if the narrator has no regard for the human existence and, in the grandeur of nature, shows that all the things which make up the lives of the six characters are meaningful to nobody but themselves.

Now, too, the rising sun came in at the window, touching the red-edged curtain, and began to bring out circles and lines. Now in the growing light its whiteness settled in the plate; the blade condensed its gleam. Chairs and cupboard loomed behind so that though each was separate they seemed inextricably involved.

who’s who

The story of The Waves starts quite abruptly, with direct lines spoken in turn by each of the six characters who are given a voice. After the first couple of pages, you realize that the friends, children at first, go a kind of boarding school together and each of them is preoccupied with one side of existence. That’s not so say they are simplistic. You get more the feeling that each of them is a side of an overarching character who floats just above the page. The narrator? The reader? Virginia Woolf herself? Maybe any and all of them.

Louis sees himself as a “boy in grey flannels with a belt fastened by a brass snake up here. Down there my eyes are the lidless eyes of a stone figure in a desert by the Nile”. His roots go back to the cradle of human civilization and historical images often occur in his consciousness.

Jinny bumps into Louis, in his state of historical transfixion, and kisses him: “kissed you, with my heart jumping under my pink frock like the leaves, which go on moving, though there is nothing to move them”. She continues searching for meaningful connections in physical relationships.

Susan sees Jinny and Louis kissing and is torn by anguish: “I will take my anguish and lay it upon the roots under the beech trees. They will not find me”. Susan is a being of nature, plentiful and bountiful, her life torn between seeking connection and longing for the solitude of nature.

Bernard sees Susan’s pain and tries to comfort her by reaching back to their common passion for writing: “But when we sit together, close, we melt into each other with phrases. We are edged with mist”. Bernard becomes the writer in the group and all friends perceive themselves in relation to his storymaking.

Rhoda is playing with flower petals: “I have picked all the fallen petals and made them swim. I have put raindrops in some. I will plant a lighthouse here”. She is my favourite character, beside the materiality of things, undistinguishable from her own perceptions, always in search of a self.

Neville sees Bernard going after Susan and perceives him as “seaweed hung outside the window, damp now, now dry. I hate dangling things. I hate dampish things”. He hates being seen, yet he is the one observing Percival, too afraid to express his feelings.

looking and being looked at

The Waves is soaked in looking. Someone is always looking at someone else and a yet third someone sees the other two someones looking at each other. The characters are connected to each by looking, subjective perceptions and interpretations which might or might not be accurate. We never get to the “real” truth of it. It’s all just Bernard’s storymaking. In the final section, he is wondering if the six of them were ever even separate from each other.

I think that’s why I thought so much about that assignment in school while reading the novel. I was supposed to think about how I see myself, how others see me, how I would like to be seen, yet it was all just inside my head. Any control I ever had on the perceptions of others was just illusory. Virginia Woolf takes this illusion and blows it up into a flower with six petals, a center, and an eye who takes in the colour. Each petal exists on its own, yet the whole makes for the beauty of the flower.

I wrote this post after the Literature Cambridge 2024 Virginia Woolf summer school. The thoughts expressed here were fueled by Alison Hennegan’s lecture and the post-lecture seminar led by Ellie Mitchell.

your thoughts?