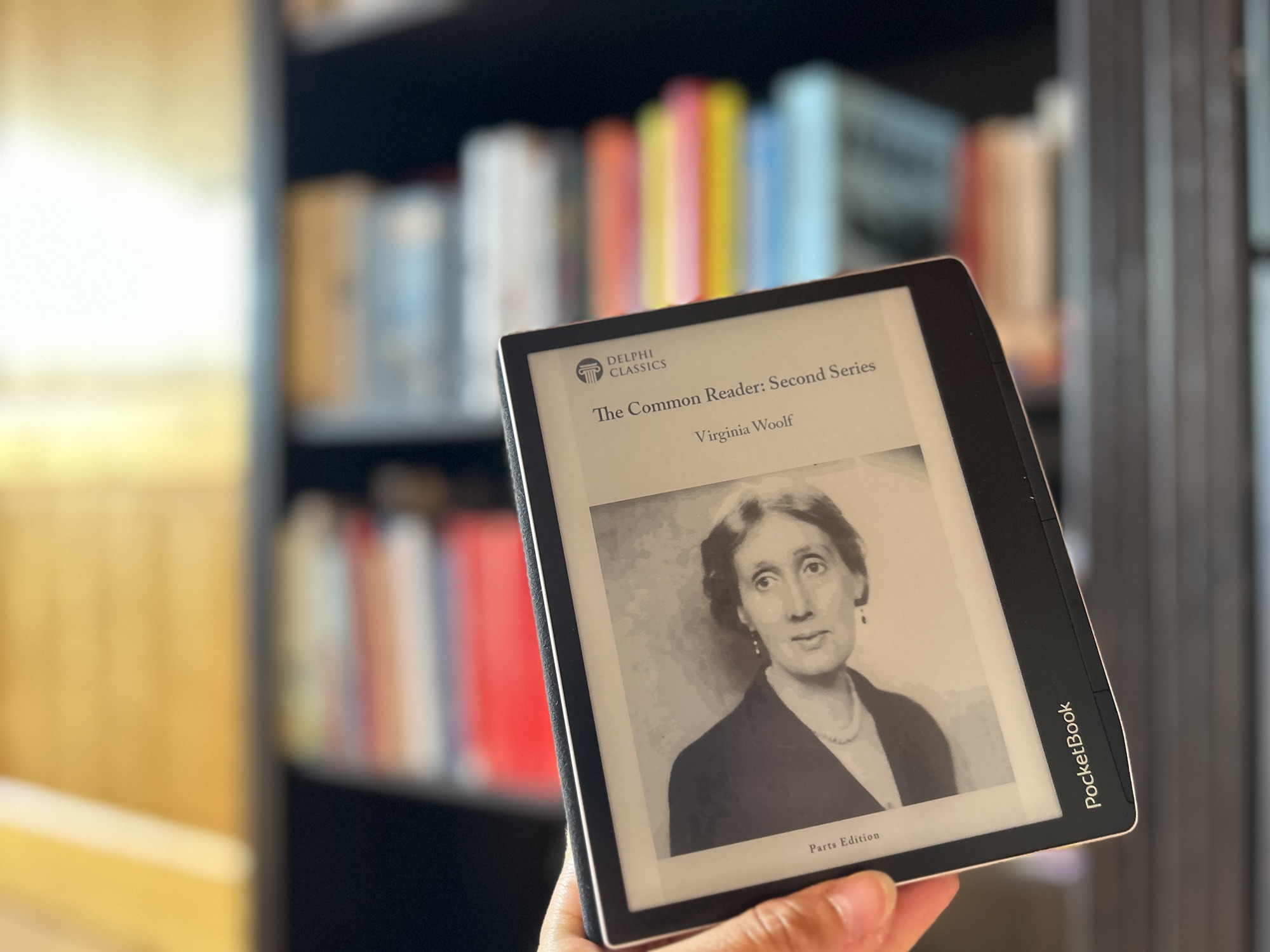

Exactly how “common” of a reader Virginia Woolf was, is rather debatable to put it mildly. In a diary entry from 1922, she writes, “I want to read Byron’s Letters, but I must go on with La Princesse de Clèves. This masterpiece has long been on my conscience”. Just to put it in context, I want to read Tana French’s latest thriller, but must go on with The Waves. This masterpiece has long been on my conscience. Woolf was not wasting time with light reading, though she does recognize that “trivial ephemeral books” do have their place in building the scaffolding for literature. She reads Elizabethan literature, biographies, essays of masters, obscure women’s lives, letters. And the desire to read and the amount of reading feeds back into her life and her writing. This is done most elegantly in the two volumes of The Common Reader, the first one published in 1925, and the second in 1932.

the common reader

The essays in the second Common Reader can roughly be split into two categories – essays where Woolf comments on particular works of literature and essays where she looks closer at the lives of authors. It happens a lot, of course, that the two intermingle. You can’t have a book without its author or an author without their oeuvre.

My favourite essay of the volume remains ‘How Should One Read a Book?’, but there are some others which pulled me back into reading them three or four times. ‘The Strange Elizabethans’ rummages among the letters of 16th century writer Gabriel Harvey and imagines a vivid and colourful image of his sister, a milkmaid who refuses to give it to the advances of a high lord. ‘Swift’s journal to Stella’ comments on the correspondence of 16th century writer Jonathan Swift with Esther Johnson, his close friend, possible secret wife. The point about many of Woolf’s essays is that she starts off with the name of a prominent man of letters and narrows down the perspective to the women in his life.

virginia woolf as a reader

Her work is permeated with her reading, which surfaces not as elaborately displayed layers of reference but in the atmosphere or structure of the novels, as pastiche or rewritings or historical reconstructions. In her essays, the distinction is eroded between reference, imitation, tribute and stealing; she works up her subjects out of a tissue of quotation and paraphrase. Her mind is full of echoes. (Hermione Lee, Virginia Woolf)

When I discovered Virginia Woolf, I came for Mrs. Dalloway and stayed for the essays. Not being really aware at first of how Woolf works an underlayer of her reading and an obsession with life in her novels, I was in awe of the technical representation of daily life. But reading more and more of her work, especially her essays, I realized that she revolutionized modern literature by drawing on the literature of the past. What is To the Lighthouse but an odyssey of the women in the novel? What is Jacob’s Room but a bildungsroman, seen through the cracked lens of memory and absence? Woolf takes structures and motifs of classic literature and subverts them to create a reflection of her age and its concerns. For her, writing is just another form of reading.

While Woolf titles her two collection of essays “The Common Reader”, her meaning is uncertain. The phrase originates from 18th-century English writer Samuel Johnson, who used it to describe a person who reads for pleasure rather than for scholarly purposes. Woolf was a self-educated reader, who had her father’s whole library at her fingertips. She read because she found pleasure in the act of reading, not because she had to teach English Literature. And her commentary on literature is not necessarily critical either. She approaches the books with love and an open mind, sees where they fail, but also sees how they enrich a readerly life. And yet, Byron’s letters and Swift’s letters to Stella? They are splinters of life, but how do they reflect our today?

robinson crusoe

Daniel Defoe’s 17th century novel remains widely read today. I remember reading it in my teens and very oblivious of the fact that the book had so much history behind it. Woolf the reader can’t just of course start simply reading the book, she ponders on the many ways to do it: “There are many ways of approaching this classical volume; but which shall we choose?” Historical context, biography of the author, own subjective perspective. Yet the book with a very material “large earthenware pot” doesn’t let go. It is by means of that pot, Woolf argues, that human perspective and nature perspective unite in the novel. “By believing fixedly in the solidity of the pot and its earthiness, he has subdued every other element to his design; he has roped the whole universe into harmony.” But to understand that, the reader needs to let herself be guided by the author.

geraldine and jane

Geraldine and Jane of the title of the essay refer to the 19th century English novelist Geraldine Jewsbury and 19th century remarkable letter writer Jane Carlyle. The essay starts with an overview of Geraldine’s biography and what kind of person the biographer makes her out to be: “something incongruous, queer, provocative about her”. The two women quickly became friends and Geraldine came to stay with the Carlyle couple for some months in 1843: “She dressed herself in a low-necked dress to receive visitors on Sunday. She talked too much. She flirted. She swore. Nothing could make her go” But the two friends continued a written correspondence until Jane’s death, which drove Geraldine into seclusion and kept her from publishing more books. She died, 22 years later, in obscurity.

The essay is at its core a celebration of the friendship between two women, who had contradictory and intense feelings for each other. Woolf brings that out in her essay, yet her tone is dialed down and things run under the cover of being discreet. She knew that even if things remain unsaid, the readers for whom the essay was written will understand what there is to understand.

what remains

I just looked at two essays of The Common Reader: Second Series, but they are very representative of Virginia Woolf as a reader. Her essays are not chunks of objective teaching which we are supposed to learn by heart and memorize for the next time we might actually read Robinson Crusoe or, who knows, Jane’s letters to Geraldine. They are lessons in capital-R Reading. They dissipate an attitude which a Reader can and will let spill into the everyday life. Consider the subjective perspective. Look at what runs behind the surface. If that’s what Virginia Woolf says a common reader is, I also want to become one.

your thoughts?