I sat down on the floor in front of my bookshelf the other day and started browsing through my old diaries from my early teens. Years’ worth of infinitesimal moments stuck to the page I wrote them on ten-twenty years ago. Some are half a page long, others two full pages. Most are what probably Virginia Woolf would call “non-being”, disparate, melodramatic and unimportant, still existing just because I was too sentimental to feed those pages to the flames. Unlike other days of return, I forced myself this time around to read these memories as if they belonged to another person. And in a sense, they did. As I read them, I remembered myself from the outside. I knew I was still myself because I have this memory of writing in my first diary, a business notebook with hard white covers and a shiny blue bookmark.

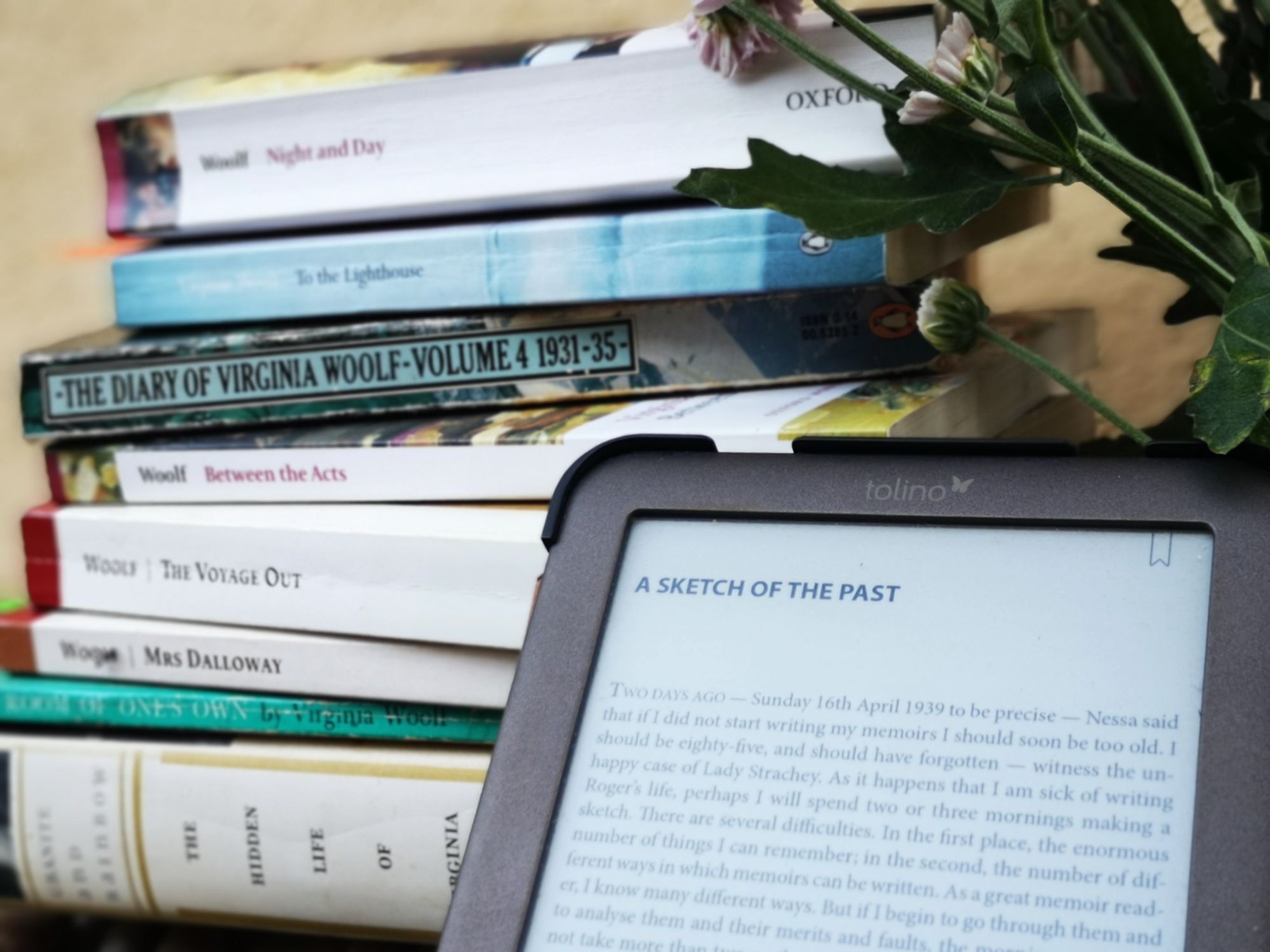

about ‘a sketch of the past’

In ‘A Sketch of the Past’, Virginia Woolf writes about her childhood self, her mother and one of her sisters from an inside perspective. The sensations she describes leak down the walls of her memories and imbibe the air she breathes with its past qualities. She brings the past back to life by inhabiting it. She exchanges the materiality of present existence with a diffuse feeling, which is at the same time touch and smell and sound and sight.

‘A Sketch of the Past’ is part of Moments of Being, a collection of autobiographical essays selected from Woolf’s unpublished writings. Like her diaries, the collection offers an extended experience of reading when comparing it to her published novels. The reading itself is skewed, and the flow of the words must be tempered by the thought that the text is virtually raw, unedited. Her published novels (and all novels, for that matter) are fully formed and polished, an objective reached. To the Lighthouse, for instance, is Woolf coming to terms with the haunting memories of her mother, and Mrs Dalloway is again Woolf coming to terms with the shreds of the post-war world. But looking at this essay and the conditions of its coming into being is like looking at the negative of a picture. It is a patchwork of manuscript notes, which the editor of the collection, Jeanne Schulkind, saw fit to put together.

Woolf wrote down her memories as a relief from the main subject she was working on, the biography of Roger Fry. The manuscript fragments are not the main thing Woolf was working on, they are not the point on which she was focusing her attention. They have that shaded quality that the edges of one’s field of sight have. When you look at an object directly and intently, you cannot help but perceive its surroundings too, if in a less than high-definition focus. The shadowy, blurry, colours and shapes of this unshapely field enhance the focus on the main object and, by contrast, define its qualities and set its limits. Schulkind put the diary fragments in a coherent storyline for the reader to follow, but it’s worth bearing in mind that these are unfocused shadows. Reading the coherent storyline, one gets the impression of the negative picture. Roger’s Fry biography disappears into the background, and the dark undertones of Woolf’s life and writing come into focus.

the nature of memory

Woolf writes that memoirs are in a sense flawed because one tends to remember places and events but that which should be the focus of the writing, the person and their character, remains elusive and untraceable. She refines the technique of autobiography by shifting the focus to the person, yet in an immaterial way. Materiality of place and, at times, immateriality of character are two extremes between which ‘A Sketch of the Past’ shifts, and this seems almost like a reiteration of a theme in an early novel, Night and Day.

One extreme is the realist return to herself as a child living with her family at 22 Hyde Park Gate, to memories of the family’s vacation home at St Ives, and to the figures she met in Kensington Gardens. She writes about her mother in the imagined Little Holland House, surrounded by imaginary tea tables and strawberries with cream, wearing an imaginary crinoline dress. These are pieces of almost realist prose, where the characters are backgrounded by that which shapes their life.

The other extreme is the impressionist style which came to define her later novels and which she uses to contain into words the nature of her retrospections. Woolf writes of her two first memories (she can’t decide which one is really the “first”, but that is nothing of importance and is more than anything a sign of the precious imperfection of memory) by the filter of perception. Her memories are not purely narrative. They are sketched by the sound the waves breaking on the beach make, and the light filtered by the blinds. Yet she doesn’t remember the sound nor the light. What she does is dive back into a “feeling of purest ecstasy,” and she describes that feeling by reflecting on the nuances of sound and sight.

In this sense then, the childhood self and the members of her family she reminisces about in ‘A Sketch of the Past’ are backgrounded and shaped by her impressionistic memories. The memories form a house built in time, the counterpart of the physical house of realist writing. Woolf pictures her mother as a member of Victorian society, backgrounded by tea parties and a crinoline dress. But she writes her mother in the wake of the nuances of the dress she remembers her mother having worn when holding child Virginia on her lap.

In 2002, in my early teens, I went on a class trip to France. It was the first time I had set foot out of my home country. I wrote my diary while lodged at the house of a girl my age, who had visited me in Romania one or two years before. Her name was Magalie and I can only remember her face now because I have a photograph of us together in a small village by the sea. The picture is blurry, but you can see my glasses, my grin and Magalie’s reddish-brown hair blown by the wind. My house of memory is built by those notebooks I have, stuffed in a paper bag at the bottom of my bookshelf, and blurred pictures tucked in old plastic picture albums, which I’ve been meaning to go through and sort at one point. Those half-forgotten moments and I form together the picture of what I believe to be me. If I look at my reflection in the mirror, I see the colours while the memories blur in the background of time. When I spend time reading old diaries and looking at old pictures, they come to the fore and make the me today a reason for their existence. We are each the negative of each other, forever building and remembering each other.

I wrote this post in preparation for the Literature Cambridge 2022 Virginia Woolf summer school. The series of lectures and seminars focused on houses, as they are depicted in five of Woolf’s works.

your thoughts?