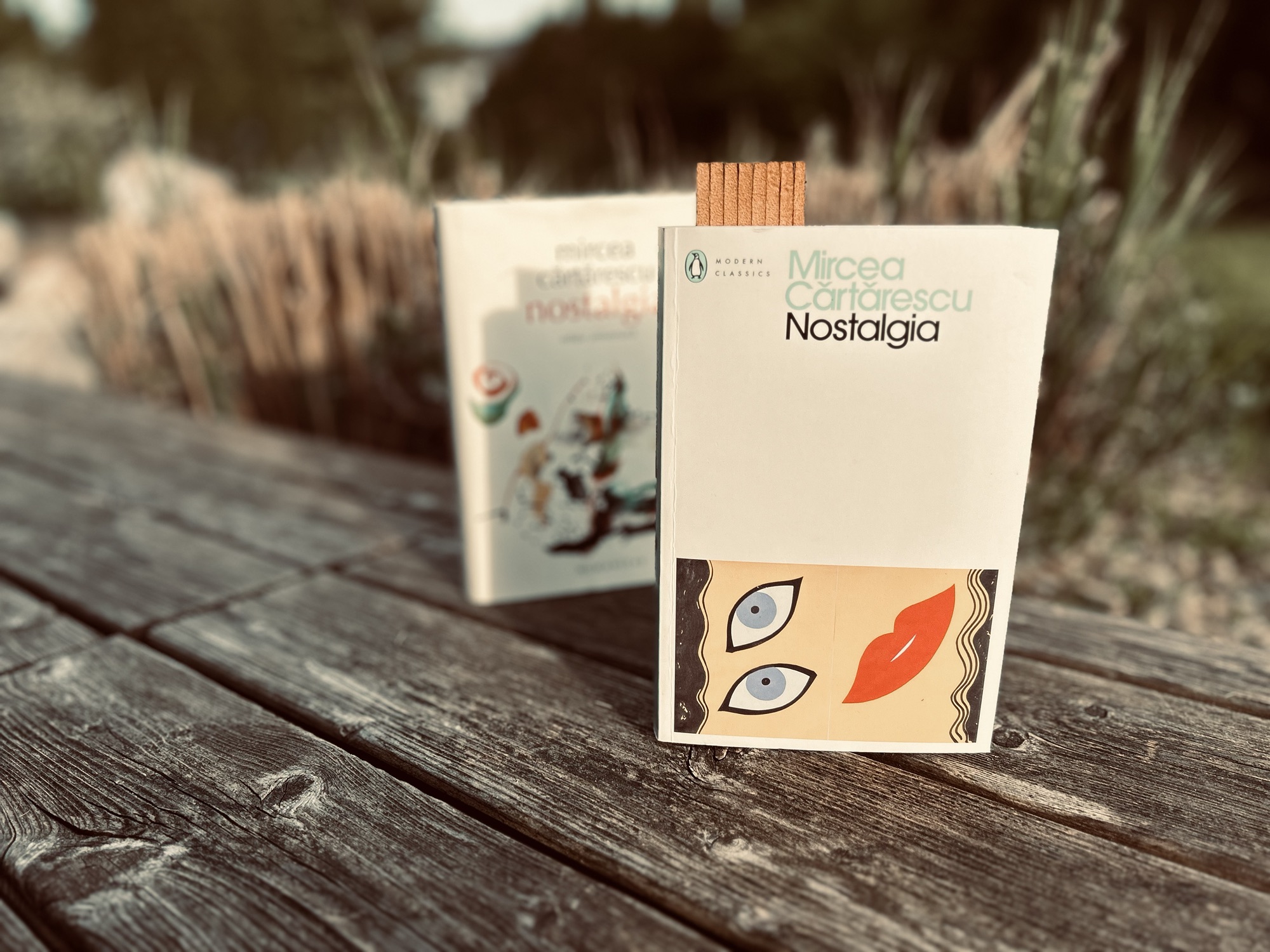

I was in Cambridge last year, randomly browsing through Waterstones when I saw it. Mircea Cărtărescu’s Nostalgia published by Penguin Modern Classics. My favourite Romanian author published by Penguin. It was uncanny. I didn’t even think twice. But I didn’t consider what a strange experience it would be to read Nostalgia in English. I’m not new to it. I first picked up the volume 20 years ago, when a friend of mine dropped it on my lap, basically forcing me to read it. Ever since then, I think I read pretty much all of Cărtărescu’s fiction and short nonfiction. Which, counting 4 volumes of short stories, 6 novels and 3 volumes of magazine articles, is no small feat.

Nostalgia is a collection of short stories and the Romanian author’s first work of prose. I say short stories just as a sort of euphemism, for they are more like novellas, and the last one is more like a short novel. The volume was first published in a censored variant in 1989, the last year of the Romanian communist regime, under the title Visul (trans. The Dream), and only 4 years later, in 1993, was the publication of the complete version possible. Ever since then, Nostalgia has become a contemporary classic of Romanian literature and has already reached its 11th edition.

stories and structures of nostalgia

Nostalgia is the product of an author who is a fan of Kafka, Borges, Garcia Marquez and Thomas Pynchon and this shows in his first work of prose. The concreteness of the stories comes second to their structural intricacies and to a continuous tug-of-war between character, author and narrator. Add this to the hallucinatory dream-world the author is building among the ruins of a gothic Bucharest, and you end up with the whole which the five stories make. ‘The Roulette Player’ and ‘The Architect’ are the prologue and the epilogue which enclose the three main stories: ‘Mentardy’, ‘The Twins’ and ‘Rem’.

I dream enormously, in demented colours.

In ‘Mentardy’ the adult Mircea, an “occasional writer of prose” as he defines himself, thinks back to a summer from his early childhood when a strange boy and his mother moved into his apartment building. The boy, nicknamed “Mentardy”, has the gift of storytelling, but things change when a traveling salesman brings his goods to the block where the children play.

After a night of agitated sleep, a horrific insect woke up transformed into the author of these lines.

‘The Twins’ is probably the most bizarre story, and you need some patience until you grasp the setting, the story, or even who the narrator is. Andrei falls in love with Gina, his classmate from high school, but she doesn’t seem serious about their relationship. But when the two go through an experience that transcends any physical and emotional boundaries, they truly begin to understand each other.

I will tell you about some things that happened to me during 1960 or ‘61, when I was still a girl, no more than 12 years old.

In ‘Rem’, Cărtărescu raises the structural stakes – we have three very different narrators, each with an apparently different goal in the act of storytelling. Nana tells her lover Vali about a summer from her childhood when she kissed someone for the first time. But the story surpasses this simple promise and encompasses the bizarre past of a family searching for “The Entrance,” Nana’s literal future on paper, and above all, the chance of a wasted life.

dreams in frames

I felt very alone, like a fallen angel, or at least one in grave danger of falling. But I knew that, in order to remain an angel, I had to ignore what I was fighting inside me, which was perhaps malignant and had progressively gained more power over me. Many times, I would wake up weeping from loneliness. (‘The Twins’)

It’s hard to describe the feeling of reading Nostalgia. Each story is set in a frame, and each story is as much about the frame as about what is actually “happening”. Yet the more you get into it, you forget that what you’re reading is a memory or a fabrication of someone who is also set in the frame of their own life and their own storytelling. For instance, ‘Mentardy’ is a story the adult Mircea finds when going through some old papers. He then says he doesn’t remember the story, but he recognizes his own handwriting. So then, is it a memory or just a performance? Questions left hanging.

The main characters in the stories are very different, yet in their loneliness and longing to dream they are weirdly fitting together. The boy Mircea from ‘Mentardy’ is young, going to school. Andrei and Gina in ‘The Twins’ are in high school, and they each live the experience of being the opposite sex. Nana is a mature woman who returns to her schoolgirl self to tell her story. They go through mysterious experiences which they innocently brush off, and their dreams of growing up finally turn into a grey reality which can only be enlivened by storytelling.

is it worth it?

To be honest, I can’t be the judge of that anymore. I’m too personally involved with Cărtărescu’s oeuvre. It’s even harder to “objectively” judge Nostalgia, because, in 2019, 30 years after its original publication, Cărtărescu published Melancolia, a sort of remembrance, return and retelling of Nostalgia from the point of view of the writer with more life experience. So, my reading is tainted. Not to mention that in English I can’t discover the feeling that reading in the original Romanian gives me. The English translation feels like a straitjacket for me. Intellectually, I know it’s there, but emotionally I can’t feel it.

your thoughts?