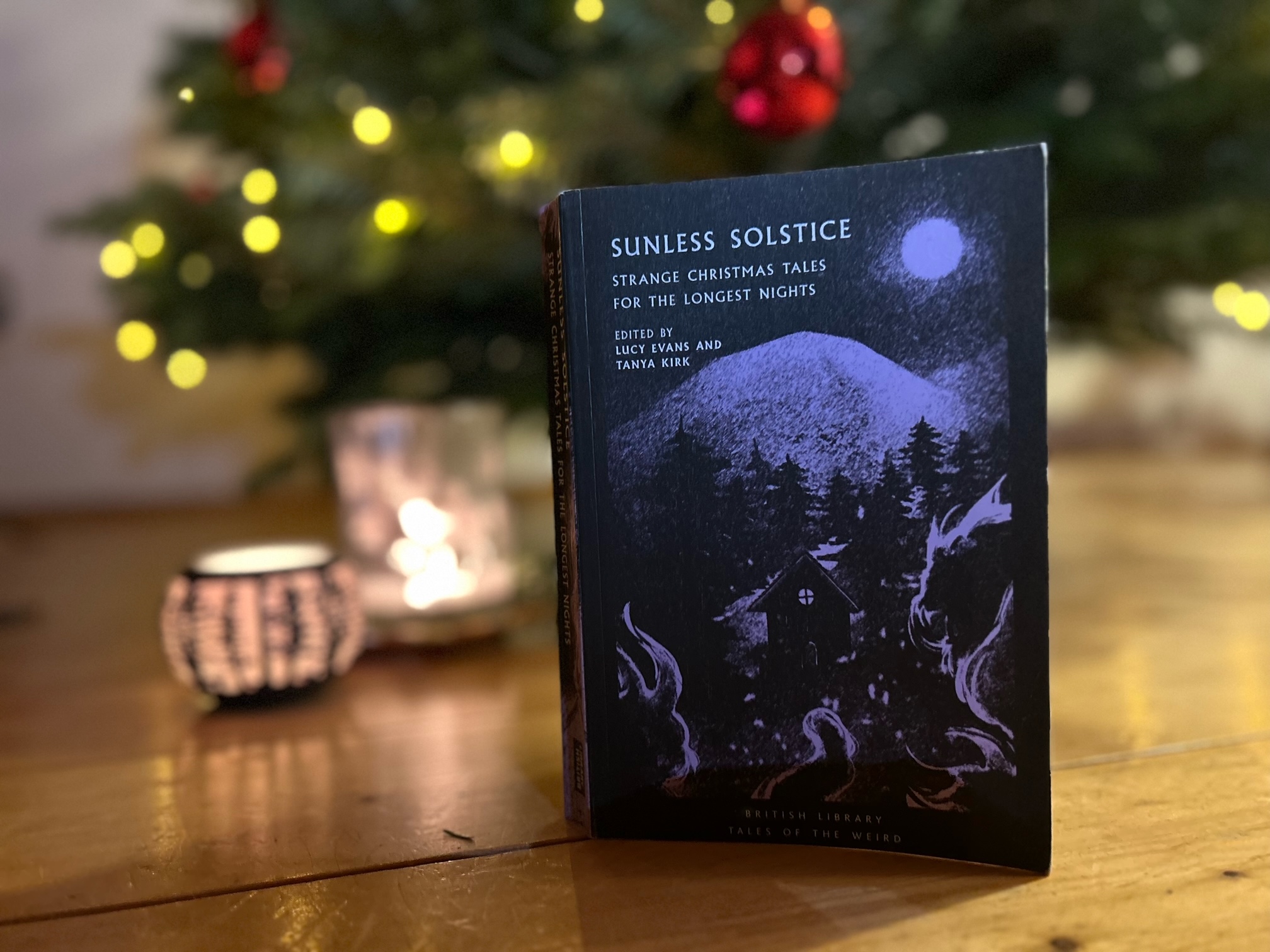

Sunless Solstice is the third in what is becoming a series of collections of dark Christmas ghost stories published by the British Library every October since 2019. I discovered this miniseries last year, when I read Chill Tidings (the second volume of ghost stories published before Christmas) and fell in love with the idea. Reading ghost stories for Christmas is a centuries-old tradition in England, but for me it was completely new. We don’t have this either in Romania, or in Germany, so I decided to make my very own tradition. And the best thing about this miniseries is that it is a subset of the larger collection of Tales of the Weird, which unearths 19th and 20th century forgotten treasures of the British Library. Each volume in the collection centers on a specific theme. Sunless Solstice gathers strange Christmas tales, while Chill Tidings features stories of a darker nature.

Most of these Christmas tales were published in literary magazines of the 19th and 20th centuries. Their authors have either had short-lived fame, or have become prolific writers, publishing hundreds of stories and several novels. Some names lie largely forgotten by now, maybe except for niche circles of readers, who make a point of keeping the memory of long-dead authors alive, while others are still widely read. I admit I am not very proud to say that in this Christmas story book, which contains 12 stories, I was familiar only with three names: Hugh Walpole, Daphne du Maurier and Muriel Spark. Luckily, I now have the chance to improve.

‘the blue room’ (1897) by lettice galbraith

Lettice Galbraith has only eight short stories, all in the vein of the supernatural, credited to her name. And that’s pretty much all we know. We don’t even know if this was actually her name or just a pseudonym, and I think that’s totally unfair. As I see it, this one story, which stacks women’s modern anxieties over layers of literary history, stands right next to Henry James and is a precursor to Shirley Jackson.

The core of the tale is a bow to classical dark Victorian Christmas stories. A group of friends spends Christmas at the mansion of one of them and, when there is talk about strange deaths and a possibly haunted room, one of the young women in the group declares herself ready to spend the night in the room. In the style of old ghost stories, the tale is told by a supposed eye-witness to the strange events which are to occur on Christmas night. In this case, she is housekeeper of the mansion, who looks back at what happened, and says that “Mertoun has been my home from the time I was eighteen”. The voice of the housekeeper gives the story a modern feel. She remains an outsider, nameless, helper to her aunt, whom she plans on succeeding. But she’s not just a voice who tells a ghost story. She is a person with fears, a past, knowledge of history and empathy for the women at Mertoun.

‘ganthony’s wife’ (1926) by e. temple thurston

Mr Northanger, the narrator in Thurston’s story, tells a story which is “not for children. They wouldn’t understand it and that’s the first quality required of a ghost story.” The story charmed me because of two things. First, the descriptions of snow falling on the streets of London really bring in that atmosphere which we so long for right now in a snowless December: “It was snowing then, coming down like a black fog over the black darkness outside”. Second, the strangeness of the story lies in its pairing of a very flesh-and-blood woman figure to a ghostly, disembodied figure. Mr Northanger tells the story of how he met Ganthony, an acquaintance of his, on a Christmas afternoon and learned of Ganthony’s wife’s death. On his way home, Mr Northanger meets a mysterious female figure, to whom he immediately feels attracted, and who then accompanies him home. The surrealist feel of their encounter is strengthened by the snowstorm and overshadowed by the immaterial presence of Ganthony’s wife.

‘the apple tree’ (1952) by daphne du maurier

Daphne du Maurier hardly needs an introduction. Her stories are on the verge of the supernatural and the reader is never really sure if it really is something supernatural in the middle, or it’s guilt which weighs heavily on the consciousness of the characters. I reread Rebecca recently, which gave me an impulse to read her short story ‘The Birds’. There is definitely something supernatural at stake here, because, from the perspective of a farmer living on a remote island, there is nothing to account for the aggressive behaviour of birds. But that’s less interesting. The interesting part is how the farmer’s family comes to terms with the unknowns of nature.

‘The Apple Tree’ also has nature at its core. A rich widower is plagued by the memory of his dead wife, who he feels is somehow returning to haunt him in the form of an old apple tree. Like in Rebecca, the absent, dead, wife is the main character, and the husband tries to escape her memory. But what’s interesting in ‘The Apple Tree’ is that we soon realize how unreliable the story of the widower becomes. How he portrays his wife, his relationship with the neighbours, his travels through Europe. In my opinion, he absolutely deserves to be haunted.

The tree was scraggy and of a depressing thinness, possessing none of the gnarled solidity of its companions. Its few branches, growing high up on the trunk like narrow shoulders on a tall body, spread themselves in martyred resignation, as though chilled by the fresh morning air.

‘a fall of snow’ (1974) by james turner

What I liked about Turner’s story was how authentic and natural it read. The narrator tells of a marking event which happened to him on Christmas when he was fifteen, visiting his uncle in the countryside. The snow plays the central role in the story, but it has a dark edge to it, because it shows an unknown landscape and hides familiarity. “Where before I knew my way about, now everything, the fields, the trees, the church, even the cottages of my uncle’s estate, was strange and terrifying”. Christmas day is ideal, covered in snow, but snow is what causes an accident, which leaves the narrator emotionally scarred.

Just as I was writing this post, I realized that each and every one of my favourite dark Christmas stories features a dead wife. Turner’s story might be an exception, but not very far off, for it does center on a dead woman, in the end. The subject is not so glaring in the context of the whole collection, but it is strange at least that, out of 12 stories, 8 feature dead wives and 4 stories of them are my favourites. Chilling conclusion for my newly established tradition though.

your thoughts?