Probably like for many readers, October and November are for me the perfect time for reading some horror fiction. Cuddled under the blanket, drinking tea blabla… I’ll spare you the clichees. But there is something soothing about horror in the dark season. I previously reviewed Sayaka Murata’s collection of short stories Life Ceremony, which is a different kind of horror than what we get in Europe. But now I’m coming back to Europe, looking together with Elinor Mordaunt at the horror in our own homes and families.

the short of it

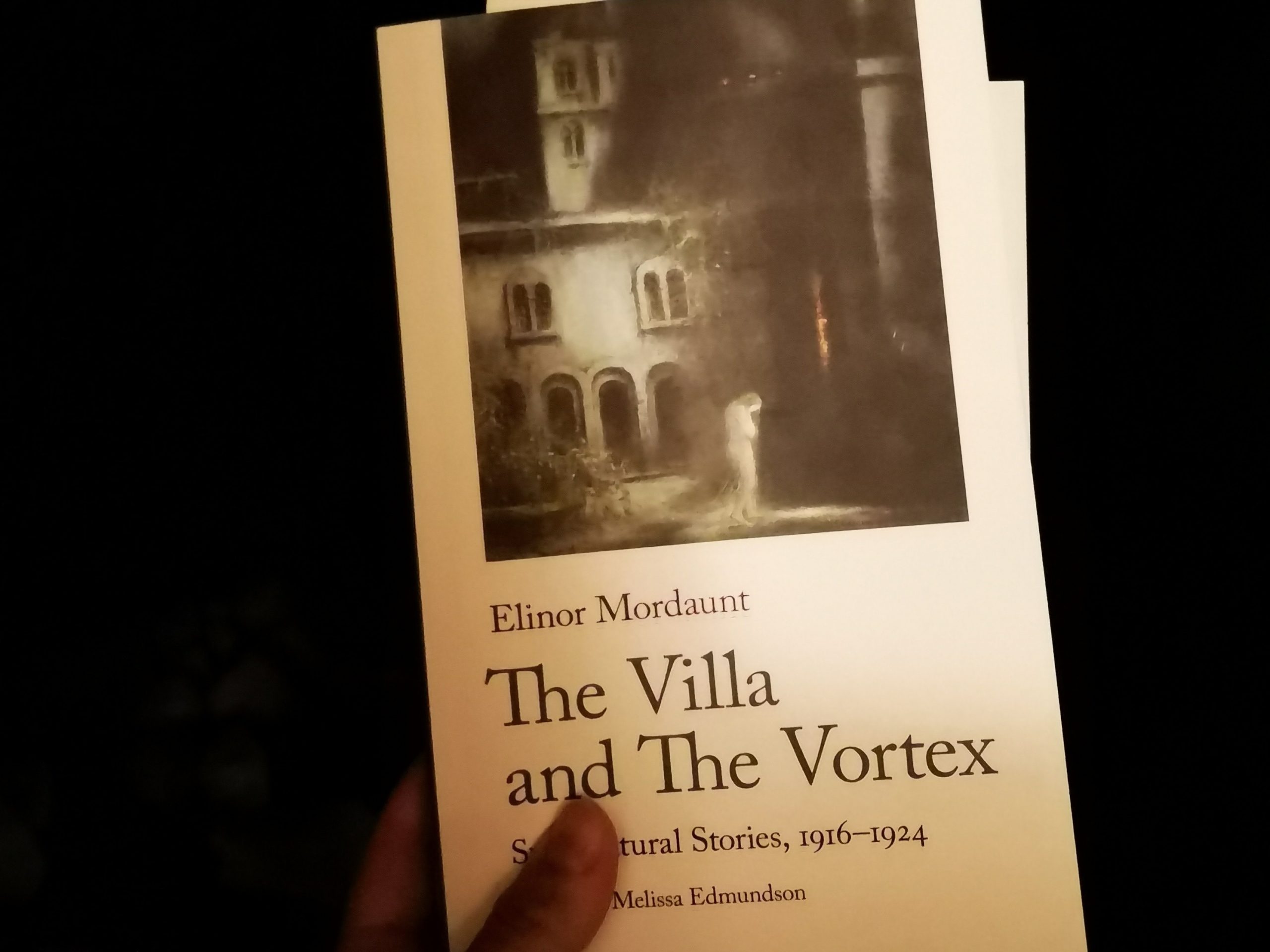

In her review of Elinor Mordaunt’s 1917 collection of supernatural fiction, Virginia Woolf writes that “it is when she is keeping strictly to what she has observed that we catch sight of those curious hidden things in human life.” Woolf admires Mordaunt’s capacity to bring her observations and experiences into her writing, except for when she resorts to “tricks” or “shortcuts”. The stories in The Villa and The Vortex, a compilation of Mordaunt’s short fiction first published between 1916 and 1924, tend to hover between these two extremes. In some stories, such as ‘The Fountain’ or ‘The Country-side’, the main character is so intricately and lightly described, barely touched upon by the narrator’s “telling,” that they feel almost modernist. But in other stories, such as ‘Luz’ or ‘The Villa’, the focus transfers to the more traditional supernatural tropes, perfect for half an hour’s intellectual entertainment.

Most of the stories are built around families, family histories and the relationships between family members, which is one reason why they are so deeply unsettling. We read about the concern of a mother for her son or shared memories between siblings, things which are so mundane that they are bound to strike a chord with each reader. The horror does settle in more clearly when the tensions between family members are revealed to be of a supernatural nature, but that recognition of daily life is what makes the stories so uncanny. On the one hand, the stories are grounded in a form of psychological realism, which drives their supernatural development. Yet on the other hand they are as far away from realism as supernatural stories go.

generational trauma

In ‘The Weakening Point,’ for instance, the Challices are concerned about their son’s Bond gradual estrangement and unstable mental equilibrium. To use Woolf’s word, Mordaunt uses a supernatural “trick” as the reason for the son’s development throughout his life, but the underlying concern which Mordaunt expresses is all too recognizable: no matter what the parents do and what they wish for their children, children are bound to go their way, even if that way leads to a dead end. ‘Four Wallpapers’ is for me the most complex of the family stories in the volume. When a young couple moves into a Spanish villa in Tenerife and starts renovating it, they discover a more sinister story plastered into the very wallpapers of the drawing-room. In tearing up the old wallpapers layer by layer, the wife discovers the tragic story of each generation of the family who lived there before, starting with the latest to the oldest. From end to beginning, that is. The rearrangement of the events seems to suggest that nobody can select the cards they are dealt, and trauma has a way of insidiously installing itself in each generation.

social commentary

Under the surface of horror and the diffuse feeling of disquiet which the stories give off, some of them are built on a layer of social commentary. ‘The Weakening Point’ is probably the clearest example of how the rich and the poor interact with and see each other. Bond Challice, the inheritor to the “spacious beauties of Challice Court”, is plagued by debilitating nightmares every year on the night of his birthday. The only one able to offer real support is Patterson, a school colleague of “a different class.” A friendship develops between the two, and Bond’s mother knows that Patterson will help his friend “whatever it may cost you.” She has little regard or knowledge of the very material sacrifices Patterson must make in order to be there for his friend on the night of his birthday. The story offers insights into the relationship between classes in the England of WWI, how men and women are supposed to behave, but also that only the rich can afford to suffer from mental instability, while the poor must bear their cross in silence.

supernatural horror

If the social commentary and the family relations are the hidden skeletons, it is supernatural themes which constitute the flesh and feel of the stories. The beginning of almost every story makes Mordaunt’s intentions clear and draws general lines as to what the story is “about” (at one level, at least). ‘The Country-side’, a story of alleged witches and witchcraft, and which weights religion and superstition against each other, has a “preamble” whose purpose is to instill in the reader the idea that “those early roots of our Christian faith are still instinct with a sinister life.” ‘The Vortex’, a story which blurs the boundaries between the theatre actors’ real life and stage persona, reads as the bone-chilling variant of Virginia Woolf’s Between the Acts. While Woolf’s 1941 novel metaphorically suggests that real life unfolds on a theatre stage, Mordaunt takes this hypothesis to a skin-crawling conclusion, asking if it’s possible that actors “lose their real characteristics and become part of [the play].”

drawing the line

In the short fiction of The Villa and The Vortex Mordaunt infuses a faint feeling of uneasiness into scenes of daily life. This diffuse feeling then rapidly slides into the territory of the dark and the unknown. Her stories seem to suggest that it is enough to lift a loose corner of the colourful wallpaper of the everyday to reveal “not a mere absence of light, but something tangible, alive, threatening.” No wonder the tea gets cold…

your thoughts?