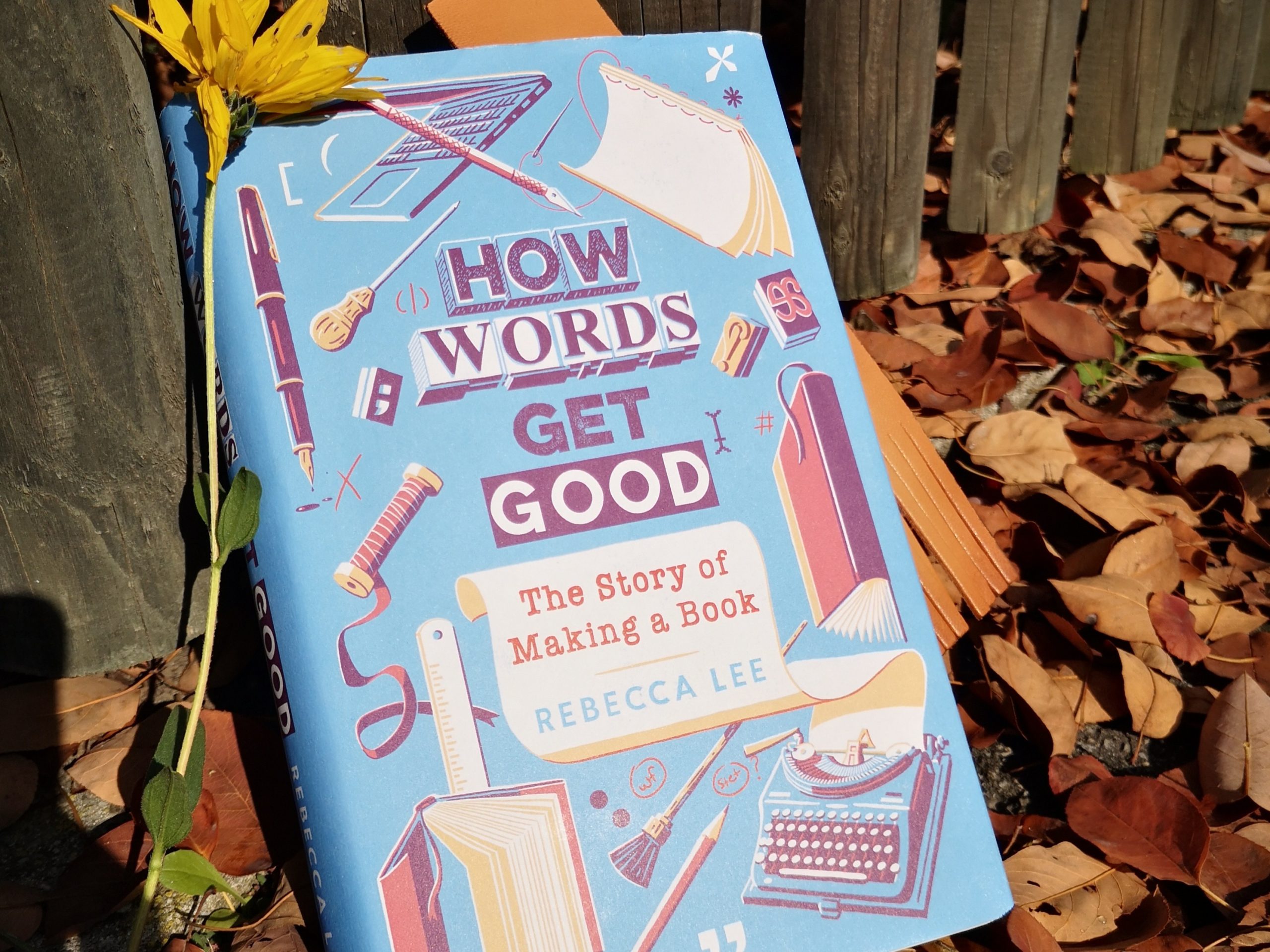

The title of this book about books makes you look twice: How Words Get Good. It’s bold and loud; twisted, enticing and musical, like the waterfall which turns a serene river into a stony chasm. Reading the book, words lose the impersonality of the measurement tool and become part of the message, the message aware of itself.

Rebecca Lee, the author, spent twenty years working at Penguin Press making books – and the words which make up books – good, better and free. She is our perfectly qualified, funny, and friendly guide through an industry which seems, from the outside at least, to be inaccessible and wrapped up in itself.

a book about words

It took me some tens of pages until I understood the depth of the language contortion occurring in the title and recurring throughout the book. In quite a lot of cases, “words” is interchangeable with “book,” and this serves two purposes. First, it sheds light on the fact that, just as a book is made of words, the author of the book is supported by tens (if not hundreds) of people who help them bring their ideas out into the world. Quite often, readers see a book as the product of a single person’s mind, but as Lee shows us (and probably as each of us know but maybe prefer to repress), this is too romantic an idea for the book industry today. Second, because a book is made of words, each of these words needs to be paid special attention to. This is how it brings out its best side and makes the book the best book possible. How Words Get Good is a book about books, but foremost, it is a book about words.

good words

The adjectives I used in an earlier paragraph to describe the stages a book goes through don’t belong to me. These are the three chapters in which Lee* organises her own words. First, words are born, and they are good. This is where Lee tells us about the world of authors, ghostwriters, agents and editors. As a common reader having little to do with the publishing industry, I was most intrigued by ghostwriters. Lee shows us ghostwriting’s “distinguished and intriguing history” by giving us a peek into the less-known background of books by well-known authors such as Harper Lee and H.P. Lovecraft.

better words

Then, words get better. This chapter is where the book geek gets their money’s worth. Lee shares behind-the-scenes stories of how things sometimes go wrong in matters of grammar, punctuation and spelling. Nobody likes mistakes, but what a world of meaning can they open! We learn that Charlotte Bronte wrote “fight letters” (not eight), and F. Scott Fitzgerald was terrible at spelling. A copy of the first edition of The Great Gatsby printed with a lower-case ‘j’ for Jay might sell for an impossible sum of money, but how much would one have enjoyed reading Fitzgerald’s drafts, in the end made better by his editor?

free words

Finally, words are set free by translations, blurbs, book covers, text design and print. All of these are sometimes taken for granted, but each adds to the meaning words carry and how they are perceived by the reader. A translation made by a “roundhead” in a literal way and as-close-to-the-original-as-possible is one thing. Yet something else entirely is a translation by a “cavalier” who recognises the gap between the culture of origin of a text and the target culture, and uses their own words to close (more or less successfully) that gap. Blurbs convince the hesitant reader in the bookshop to invest their money in books (with “adjectives and superlatives [that] have become increasingly heightened”), while text design and placement on the page also show, not only tell, the story.

my words

What I most enjoyed while reading this book about books was the feeling it gave me, of talking to a friend who is knowledgeable about and well-versed in the publishing process. The language is free and informal; you get bits of history, anecdotes from the lives of books and their authors, and even advice for your own reading and writing life. Much of it comes from the horse’s mouth too, since Lee makes no secret that she has friends in high places. Almost every section in the book is backed by the work experience of copy-editors, translators, and ghostwriters. I can only say, I want the rest of the story too. You can’t confine publishing to 300 pages.

* Lee’s fondness for footnotes is contagious. In a podcast, Lee says that she was approached with the idea and title of the book, and her editor helped her improve its structure. It’s funny that, as a reviewer and a reader, one always refers to any written element of the book as coming directly from the author. In itself, this is a fallacy, but we can’t reasonably know this. Is the publishing industry double-crossing us?!??

your thoughts?