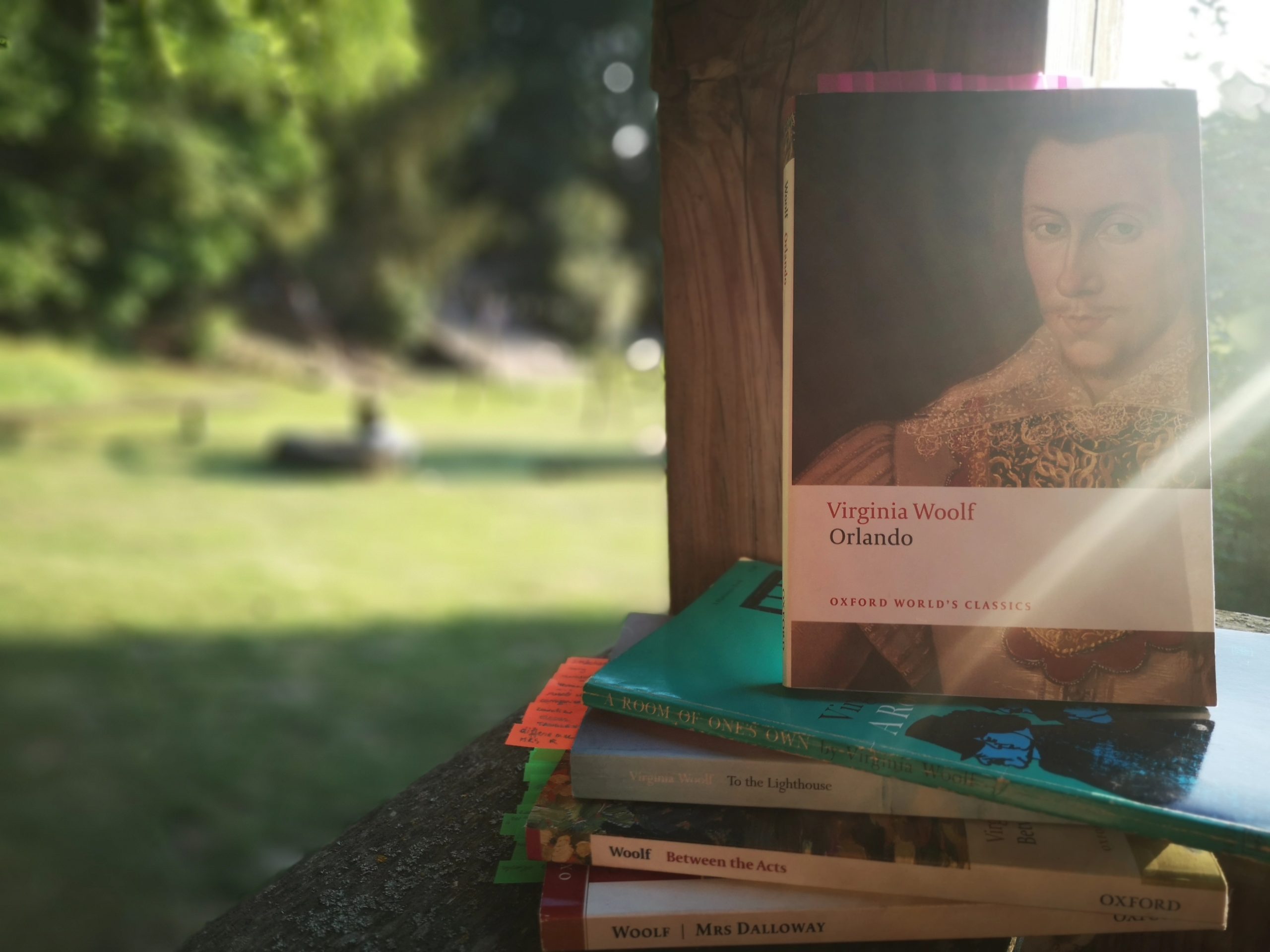

I love being wrong, I love forgetting things and then coming back to them, rediscovering them and enriching them with new experiences. I wrote in the previous post on To the Lighthouse that Virginia Woolf’s novels have a thin storyline, but I realize now that when writing that I had failed to take Orlando into consideration (not to mention A Room of One’s Own, Orlando’s nonfictional twin, and, as I think of it now, one of the earliest examples of what we would call today “narrative nonfiction”). The novel has a rich narrative structure, a twist, plot and storyline, and is pure fun to read. Now, I don’t want to fool anyone. This is not Stephen King we’re talking about. This is both a mock biography and a heartwarming story centered on a character derived from the writer and aristocrat Vita Sackville-West, one of Virginia Woolf’s most intimate friends. But a bit of background detail is necessary to grasp the nuances and private jokes Woolf references. Luckily my Oxford World’s Classics edition, complete with introduction and explanatory notes, took care of that for me.

Orlando is no doubt very much entitled to a biography. The matter which lies at the heart of the story, the event placed pretty much in the middle of the text, at the end of chapter 3, is that Orlando goes from being a man to being a woman. Full stop. Deal with it or don’t, believe it or not, this is the Truth of it. It even prevails over Purity, Chastity and Modesty, the ladies which in the Victorian age (maybe even now?) would have been lighter on the eye and the senses. But before we go into the much more serious matter of how male Orlando and female Orlando experience the world and the centuries, I would like to spend a paragraph thinking about how biographical this “biography” is.

Orlando is born as male, in the 16th century, the Elizabethan age, and lives until at least 1928, when the book ends and he/she is female and about 35 (as good as anyone’s guess). Age is of little matter, for we are not trading in realism, nor fantasy, nor biography, nor history. As mock biography, the book is a mixture of all and none. The biographer and Orlando (maybe even the reader) are caught in a game of hide-and-reveal and it’s not always clear who holds the upper hand. At times she is a fictional character, reminding me of Mrs. Dalloway on the streets of London: “She walked on without thinking, up one street and down another” while the biographer tries to catch up. At other times, the biographer is in the same room with Orlando, trying to find material for their book: “At this moment, but only just in times to save the book from extinction, Orlando pushed away her chair, stretched her arms, dropped her pen and came to the window”. Biographical details which nod in the direction of Vita’s own “brown earth” roots are not missing either: “a certain grandmother of his had worn a smock and carried milkpails”. We soon realize Woolf is not writing a traditional, Victorian-style biography. She is meditating on the nature of fiction and writing.

The stories of male Orlando and female Orlando are both adventurous and both intensely preoccupied with love (and its flavours: same- and opposite-sex attraction, exciting cross-dressing, and delicious androgyny) and creativity. Female Orlando is more privileged from a certain point of view than her male persona because she gets to have the life experience of both sexes. I wonder, though, how “fair” it is to say that. Cultural influence plays a great part in how both sexes of Orlando see the world and are seen by it. Can one say that because female Orlando knows how it is to be man in the Elizabethan era, she knows how it is to be man? As we see in the book, time, trends (and weather) change. “Man” and “woman” also do, as much as something essential in Orlando might struggle to stay the same.

As a young boy, male Orlando grows up in the historical shadow of his ancestral home, enjoys the favours of Queen Elizabeth I and is sent on political travels to Scotland. He visits the taverns in Wapping, where “the cheek of an innkeeper’s daughter seemed fresher than those of the ladies at Court”, yet he soon tires of “sailors’ stories” and turns to writing ever so often. After going through what we would call a hard break-up with Russian princess Sasha, his literary inclinations take a dangerous turn.

For once the disease of reading has laid upon the system it weakens it so that it falls an easy prey to that other scourge which dwells in the inkpot and festers in the quill. The wretch takes to writing.

Orlando starts writing his (later her) major literary creation, the long poem “The Oak Tree”, but when Nick Greene, a well-respected writer and critic tears his writings apart publicly, Orlando decides his legacy is his country estate. He “resolved to devote himself to the furnishing of the mansion”.

While female Orlando spends her days on English soil, her preoccupations are no different from what they had been when she was he. Because “the change of sex, though it altered their future, did nothing whatever to alter their identity”. By the time female Orlando emerges, we are in the middle of the 18th century, which had bred its own literary personalities. Orlando finds herself in awe of Addison, Dryden, Pope and becomes a literary hostess only to “pour tea for them all”. We hear no debates during her salons, we only learn the great writers “taught her the most important part of style”. Yet critical thinking does form, something which I couldn’t see in male Orlando. In a masterfully visual scene of Orlando in the carriage with Pope, Orlando perceives the light and shadow of her own views. Selfishness and blind admiration lie in shadow, while cold, hard light shines on the simplicity of human condition.

Orlando splits his/her 400-year life span between being man and being woman, yet the 400 years are a large sweep of history, customs, social development and society itself. The biographer seems aware of these changes, yet Orlando barely perceives them. By 1928, she is an accomplished writer, had a child and is about to meet again her husband after a separation. Life prevails. It doesn’t care of ancestral homes, change of sex and memories of the past, yet this is what it’s made of. I just can’t but wonder what male Orlando would have set out to do with a female knowledge of himself.

I wrote this post after the Literature Cambridge 2023 Virginia Woolf summer school. The thoughts expressed here were fueled by Alison Hennegan’s lecture and post-lecture seminar.

your thoughts?