I came across Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse while studying modernism in 2021. Before that, I had read a couple of her essays and, of course, Mrs. Dalloway. How much had stayed with me after all that is another question, because I only properly started immersing myself in her works after the second reading of To the Lighthouse. It’s certainly not an easy read, not even after three or four revisitings. But you start enjoying letting your mind wander, because then you can pull it slowly back to the text and find yourself suddenly deep within the wanderings and musings of Mrs. Ramsay, Lily Briscoe or Cam. You discover something else about the characters and about yourself because you see your mind functioning as their minds, you perceive them to be just as real as you are. And yourself, just as real as they are.

Calling To the Lighthouse a novel with a “plot” feels almost like missing the point. What Virginia Woolf gives us instead is an elegiac piece of writing, in which the rhythm of thought, memory, and presence is carried by the people who inhabit a summer house on the Isle of Skye. At the center of To the Lighthouse stands Mrs. Ramsay, whose presence binds everyone together—her eight children, her husband with his brooding need for admiration, the painter Lily Briscoe, the elderly poet Augustus Carmichael, and a couple she’s determined to see engaged. But it’s the house that reflects Mrs Ramsay most fully. She tends to it as she does the people around her—illuminating it with care, smoothing over silences, filling rooms with her presence. Over time, her presence becomes part of the place itself. When war and death sweep through the narrative in a few brisk, almost indifferent lines, it’s the house that holds the memory of her—the absence shaped like a person. The return, the unfinished painting, the long-postponed trip to the lighthouse bear Mrs Ramsay at their core, and bear the echoes of a place and time that was once full of her.

the house of to the lighthouse and mrs ramsay

The vacation house is more than a stage for the emotional tumults of human existence the reader is made privy to. It is a character in itself, and it forms a shape for the slippery figure of Mrs. Ramsay. The first part of the novel is called “The Window” and, among other things, it offers a narrative frame for the artistic preoccupations of Lily Briscoe. Lily works on a painting of Mrs. Ramsay and James, as they sit together in a window of the house. But, while Mrs. Ramsay poses for the portrait, her mind is one with the sound of the sea and with the sounds of the house. The sea is a “gruff murmur… a ghostly roll of drums remorselessly beat[ing] the measure of life”, it is the uncertainty of the future and the horror of unescapable death. To that, the house offers comfortable refuge: “the taking out of pipes and the putting in of pipes which had kept on assuring her that the men were happily talking… the tap of balls upon bats of the children playing cricket”. Mrs. Ramsay lives in the house while keeping everything else safe at bay.

While knitting stockings for the lighthouse keeper’s boy and asking James to serve “as a measuring-block”, Mrs. Ramsay’s eyes measure the rooms of the house. “Saw the room, saw the chairs, thought them fearfully shabby.” For her, the house is a place which the children loved, and which provided a distraction for her husband. Old chairs, mats and flapping wallpaper fill the rooms, all touched by the mark of time, but not the books. “Disgraceful to say, she had never read them”. Mrs. Ramsay’s life is not in the books, like her husband’s is, but in the narrow corridors of time which are made visible by the decay around her.

mrs ramsay in a past house

Towards the end of the day, when the Ramsays and their guests sit down to dinner, the conversation between the characters, and, even more, their inner thoughts and mood shifts, reveal deep drifts, but also deep connections. But the words they speak are very much on the surface of the entangled threads which bind them together. Mrs. Ramsay and her husband have a subtle fallout which crawls to the surface in a later scene, when she doesn’t offer him the “sympathy” he is so dependent on. Lily, under the subtle influence of Mrs. Ramsay’s gaze, does offer her sympathy to Charles Tansley, as if to a child who needs encouragement and support. But the scene is a painting of the relationship one has to oneself, as much as it is a painting of social relationships.

And as he was grateful, and as he liked her, and as he was beginning to enjoy himself, so now, Mrs. Ramsay thought, she could return to that dream land, that unreal but fascinating place, the Mannings’ drawing-room at Marlow twenty years ago; where one moved without haste or anxiety, for there was no future to worry about… Life, which shot down even from this dining-room table in cascades, heaven knows where, was sealed up there and lay, like a lake, placidly between its banks.

Mrs. Ramsay, as Mrs Dalloway, also a perfect hostess. She allows herself to settle within herself only after her husband is content. Her reminiscences of a drawing room in a house twenty years before reveal a deep preoccupation with a life lived on shores washed up by time, with complexities which the passing of time brings. The moment in the present time, at the dinner table, is superposed on the moment from the past in another house, at another table, and the reader is left wondering where the real lies. Is life sealed in a memory of the past, near or far, or is it a story the end of which is yet unknown?

other houses of to the lighthouse

To the Lighthouse, and Mrs Ramsay, are endless. This time I thought about how the house forms the idea of Mrs. Ramsay and I could barely cover some basics. I didn’t even begin to write about the “hive-shaped dome” which Lily Briscoe sees when painting Mrs. Ramsay and James, the inside and outside spaces kept apart by the windows which reflect the in and keep the night at bay, the house of memory which Lily returns to after 10 years and she tries to find or re-invent Mrs. Ramsay again. For Woolf, the house is more than a domestic space controlled by feminine figures. It is a place of refuge, reflectivity and self-creation which form the basis of character and personality.

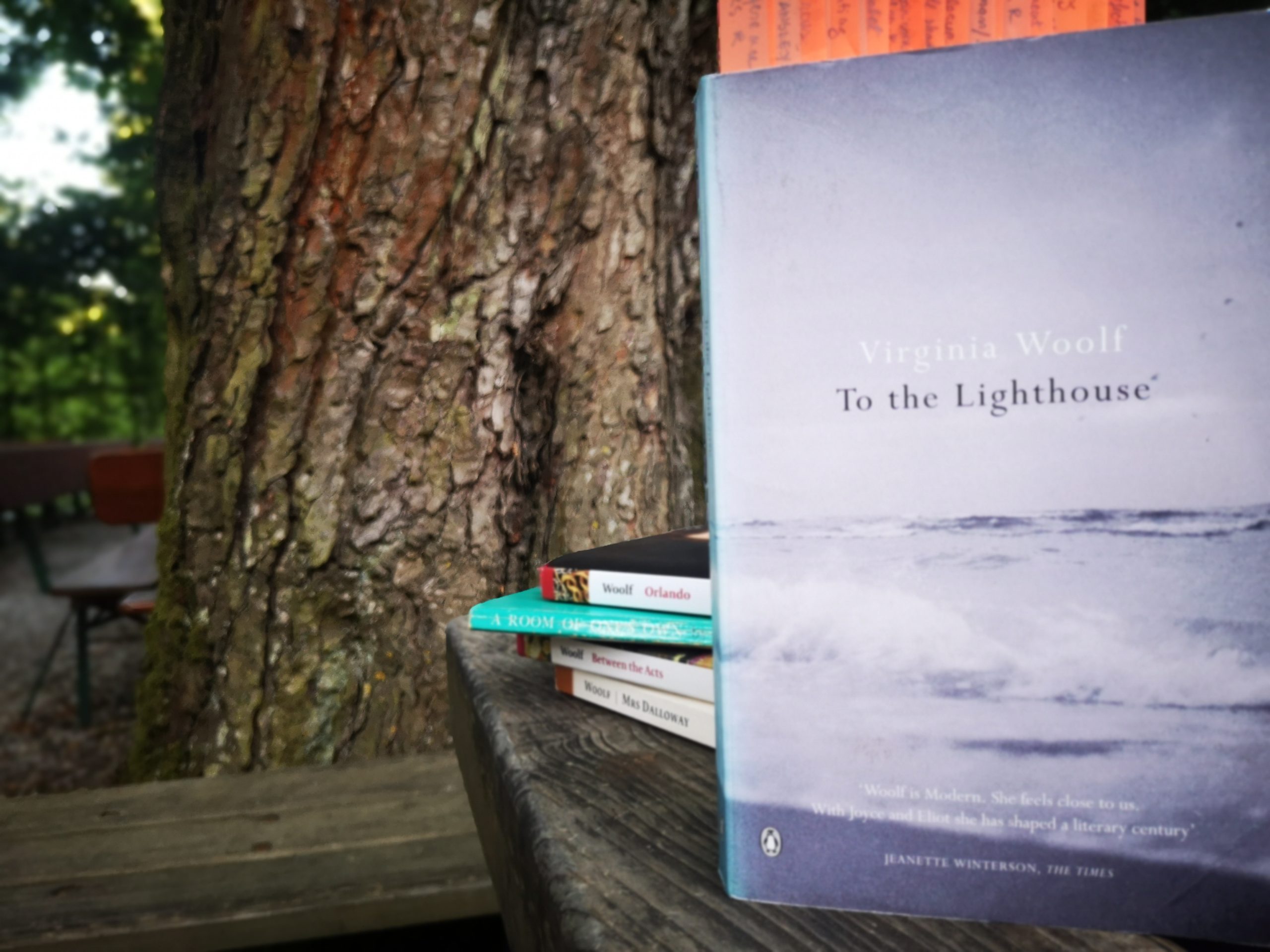

I wrote this post after the Literature Cambridge 2023 Virginia Woolf summer school. The series of lectures and seminars focused on the houses in five of Woolf’s works.

your thoughts?