I don’t remember much about the first play I ever watched, but I remember one thing – I didn’t understand a single word of it. It was Chekhov’s The Seagull. For some reason, the school thought it was a good idea to send a bunch of 12 (or 13) year-olds accompanied by a few teachers to watch the new enactment of one of the playwright’s major plays. I clearly remember sitting next to one of the teachers, slightly panicked, and telling her I couldn’t understand a word. The play was being performed in Romanian, that was not the issue. It was the meaning, the message of each single line that I couldn’t grasp. But I had no way to explain that. The teacher brushed me off. I should sit quietly until the end. Which I did.

In the 25 years since, I got over sitting quietly through something I don’t understand. I dig through everything I have, all the memories, all the experiences, all the knowledge and I manage to make some sense out of what seems to be an impossible text. Virginia Woolf’s Between the Acts continues to be quite impossible, even (or still) after the second reading. In her talk at last year’s Cambridge Literature summer school, Professor Claire Davison elaborated on the very illuminating idea that the book is built like a play. I could then at least see why this novel hadn’t spoken to me like other Woolf novels have. I’m blocked in front of a play.

Revisiting the book this year I knew at least how to read it. The novel-play stretches over a single day in June of 1939. A pageant, directed by the eccentric Miss La Trobe, is set to take place at Pointz Hall, a “middle-sized house” belonging to the Oliver family. This is the seventh year that a pageant has been enacted, and the members of the family seem to know how the day will unfold. They had rehearsed for six years. Mr. Oliver, the head of the family, lives in the house together with his sister Mrs. Swithin, his son Giles, his son’s wife Isa and their children. Before the pageant starts, two unexpected guests show up; Mrs. Manresa, “vulgar, over-sexed, over-dressed”, accompanied by William Dodge. The characters enter a dynamic web of relationships, which shifts and swings with each thought they have and each gesture they make. The pageant sweeps over the history of England and the evolution of English literature and ends in a surprising way, causing the audience to turn inwards and ask, “what meaning, or message, this pageant was meant to convey”.

Between the Acts relies mostly on dialogue and character inner speech to move forward, while the narrative fragments read more like stage directions. A dialogue on the topic of a failed county council project on the evening before the pageant opens the novel. “What a subject to talk about on a night like this”, remarks Mrs. Haines, a guest at the house. The gaps in the narrative and the abundance of dialogue challenge the reader to fill in many blank spaces and link the scenes to each other. We jump from the library to the kitchen and to the halls of Pointz Hall, able to see everything at once but missing the traditional narrative background which glues everything together. The four main female characters strengthen this image of the book, as the tensions and relationships between them develop. We see them united in their worries and interests, yet dispersed and contradictory in the outer image they project.

Isa and Mrs. Manresa are one of the two pairs which stand on opposite corners of the female quartet which supports the structure of the novel. Isa is Giles’ neglected wife with “dark pigtails hanging, and her body like a bolster in its faded dressing-gown”. She secretly dreams of Mr. Haines and her awareness of his presence illuminates her awareness of the pageant. In her bedroom, she is writing poetry “in the book bound like an account book in case Giles suspected”. Isa lacks self-confidence but recognizes her inner self in the bedroom mirror. The mirror reflects her illicit love back at her, but also her prosaic life with a husband and children.

Mrs. Manresa is, at first sight, the absolute opposite of Isa. She is a loud character, reminiscent of the typical vulgar woman in a comedy of manners. Yet she is “a breach of decorum”, a “wild child of nature”. She breaks the established routine of the day of the pageant and brings fresh air (and new conflicts) to the Oliver family. Isa almost admires Mrs. Manresa and sees her as “genuine” because she believes, unlike Isa herself, Mrs. Manresa has nothing to hide. During the play, Mrs. Manresa uses her pocket mirror several times as if to signal she’s not invested in the play, yet at the end, tears flow from her eyes. There is something unclear and mysterious about her, but the outer image she projects is too overpowering for the reader to notice what is going on inside.

The other two characters which form a pair of seeming opposites in the female quartet of unity and dispersion are Mrs. Swithin and Miss La Trobe. They are both interested in art and history, if one of them is an old lady who can only imagine a dark, inscrutable, past and the other one the director of the pageant, an outsider of whom “very little was actually known”. Mrs. Swithin’s favourite read is “Outline of History”, but she can’t hold her opinions in front of her brother, Mr. Oliver, who silences her in an argument. But she has a deep understanding of Miss La Trobe’s play. Mrs. Swithin is a theatre director’s perfect audience member, one assumes, when after the play she tells Miss La Trobe, “you’ve made me feel I could have played Cleopatra”.

Miss La Trobe is no stranger to failure: “She hadn’t made them see. It was a failure, another damned failure. As usual. Her vision escaped her.” Her intention in staging the pageant remains uncertain, we only hear disparaged thoughts of audience members and, of course, see the reactions of Mrs. Swithin and, very passingly, of Mrs. Manresa. A variant of her vision has touched the audience, but she understands she can’t force her audience “see”.

I’m still not able to get over that first reaction of rejection when confronted with a play. I generally prefer opera or musicals, but I do convince myself to keep an open mind. And this is how Woolf’s Between the Acts is best read, I believe. You can’t force expectations on any of her novels, but this one requires a special state of mind. The novel builds on the idea of unity and dispersion, as we see when interpreting its elements as the elements of a play, and its main woman characters as pairs which touch common points and then quickly drift apart again. But this, of course, is only an interpretation. Who knows what Woolf wanted her audience to see…

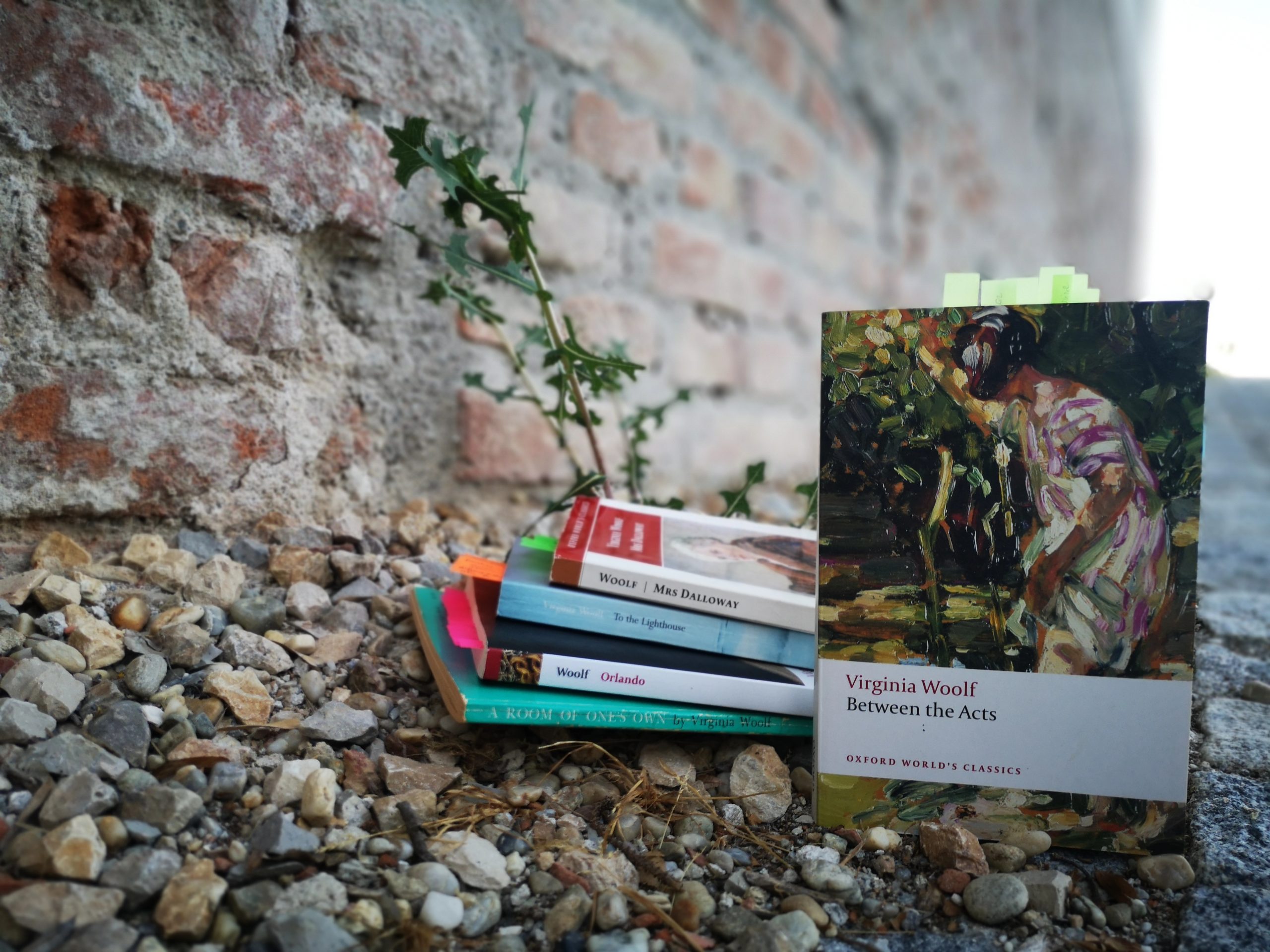

I wrote this post in preparation for the Literature Cambridge 2023 Virginia Woolf summer school. The series of lectures and seminars looks at some of the women characters in five of Woolf’s works.

your thoughts?