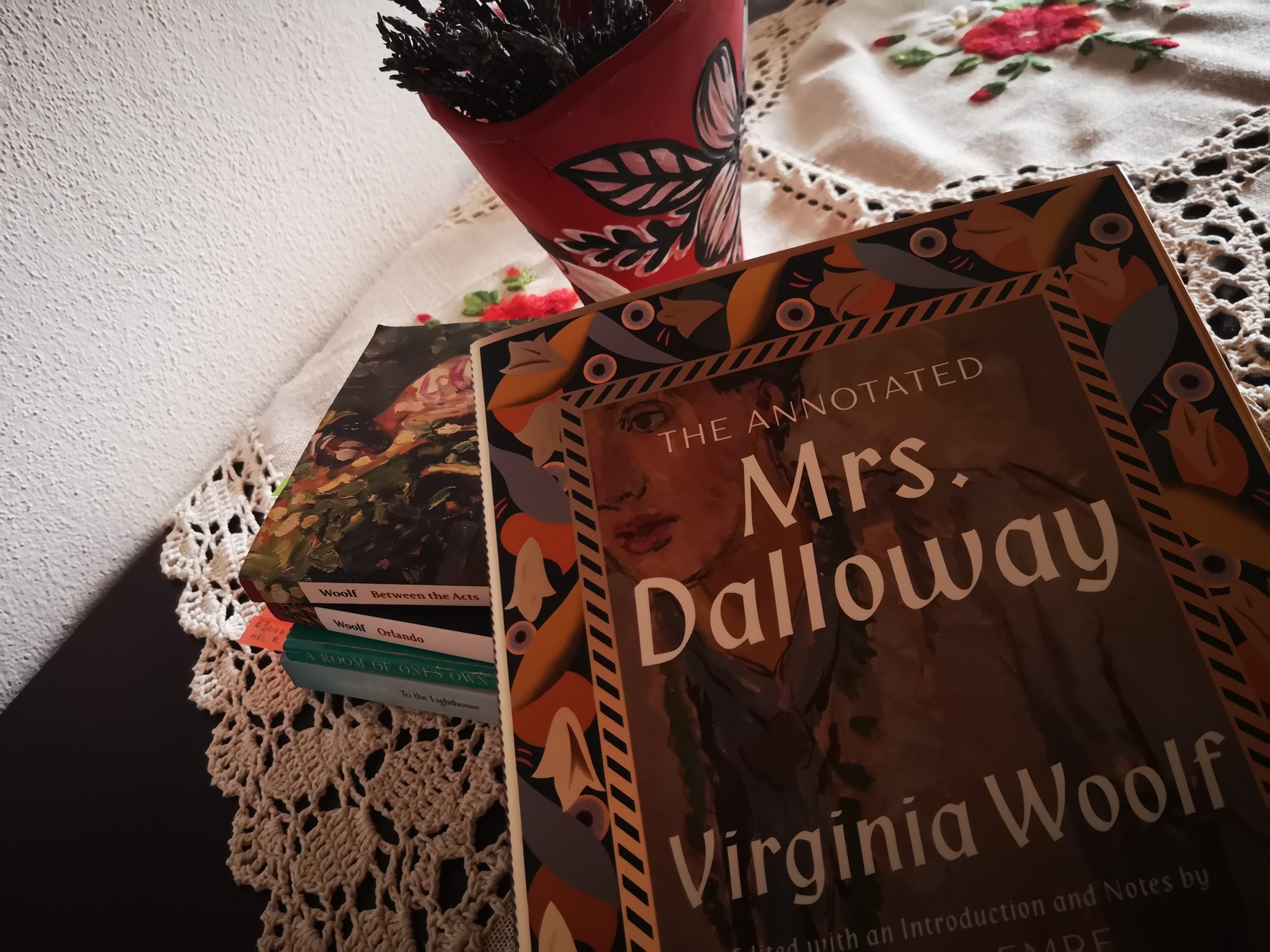

This was my second return to Virginia Woolf’s 1925 novel Mrs. Dalloway. Yes, Woolf’s novel welcomes and rewards returns more than the simple reading. It is now that I feel I can dive dive somewhat below the surface of what the novel is “about”, though even saying that feels beside the point. What interests me more are the other women of Mrs Dalloway, especially those women whose consciousness takes up barely a couple of lines of text. To notice them properly, I needed help. The Annotated Mrs. Dalloway, edited and introduced by Merve Emre, played a big role in shaping how I now understand the novel.

the annotated mrs dalloway

This 2021 annotated edition is a luxurious hardcover with a 70-page introduction, high-quality representations of photos, ads and paintings from around 1925, and more than 400 notes laid out in left and right-hand side columns next to the text of the novel itself. Mrs. Dalloway is often reduced to its storyline, which follows a middle-aged upper-class woman who throws a party and famously buys flowers. But the book I now have in my hand illuminates the novel from the inside and makes justice to its hidden complexities. It reveals rich nuances, secret connections within the structure of the text, insight into Woolf’s life, and paints a vivid picture of London in the 1920s.

Court dress from 1923. This would be the style of dress for ladies attenting Court.

The novel follows two main characters over the course of a day in June: Clarissa Dalloway, who gives a party in the evening, and Septimus Smith, whose death towards the end of the day will throw a dark shadow over Clarissa’s party. We walk around central London together with Clarissa and Septimus, as they relive memories of the past and ponder on past experiences. We come to realize that, while the two might live rather different lives, the things which are really on their mind overlap quite a bit. But this is not only a story of two characters in 1925. The particularity of Woolf’s writing is that she distances herself from the omniscient narrator of 19th century fiction and lets her characters interact with each other from within each one’s consciousness.

The Annotated Mrs Dalloway offers a rich support apparatus which fought for my attention all the time. On the other hand, it also helped me slow down my reading and take in paragraphs and sentences which I had skimmed over in my earlier readings. Woolf is known for her appreciation of “the lives of the obscure” (title of one of her essays), the overseen, the small, the “insignificant”, and encourages the reader to pay attention to that which is “commonly thought small”. But for that, the reader has to work. She has to make notes and remember pages of intricate details. Clarissa has to fade into the background and make place on the stage of the reader’s mind for “other” women of Mrs Dalloway.

In her notes on the text, Emre often returns to the matter of consciousness and how it’s depicted in the novel. She writes that a “general consciousness”, a term borrowed from the critic J. Hillis Miller, “moves in and out of the minds of characters with wonderful subtlety” and creates a “continuity of language” between main and minor characters. It’s as if the “narrator”, a term it would have never occurred to me to use for a Woolf novel, is a cosmic presence which, if not omniscient, is deeply in sync with the inner lives of characters. The minor characters might serve to give the cosmic presence a physical body, but, to stay true to Woolf’s appreciation for what is “commonly thought small”, we as readers are compelled to celebrate the life they instill in the structure of the novel as a whole.

the “other” women of mrs dalloway

One of the “small” characters which Clarissa meets is Miss Pym, the florist. Emre writes that “the minor character is used to emphasize Clarissa’s aging”. Miss Pym’s point of view flashes shortly in the avalanche of Clarissa’s memories of girlhood: “Miss Pym thought her kind, for kind she had been years ago; very kind, but she looked older this year”. We sense time passing in the mental interaction of the two women, but we can’t help but wonder why Miss Pym thinks Clarissa to be kind. What more is buried there which we don’t know because this novel is not called “Miss Pym”, but “Mrs. Dalloway”?

Mrs. Dempster “saved crusts for the squirrels and often ate her lunch in Regent’s Park”. We meet her in Regent’s Park indeed, after Maisie Johnson to whom “all seemed, after Edinburgh, so queer” asks Septimus and Rezia, his wife, for directions to the tube station. We only learn of Maisie that she was only nineteen and “had got her way, at last, to come to London”, and then we never meet her again. Mrs. Dempster takes in Maisie’s youth and thinks back of her own life, which “had been no mere matter of roses.” Mrs. Dempster brings, just like some pages earlier, Sarah Bletchley or Emily Coates, little insight into Septimus or Rezia. But they are part of the murmur of life, war and reconstruction which populates Regent’s Park and Mrs. Dalloway’s London.

Regent’s Park. 1935 painting by Duncan Grant

But life doesn’t only reside in the present, it fuels the past as well. Clarissa often thinks back to her girlhood and youth at Bourton, where she met her husband, Richard, and rejected the marriage proposal of Peter Walsh. Peter adds his point of view to the richness of details which form Clarissa’s past. From his musings we learn that Clarissa had a sister, Sylvia, whose death was “a horrible affair” and caused Clarissa to turn to atheism. An interesting detail which Peter remembers is Clarissa’s old nurse who lived “in a little room with lots of photographs, lots of bird-cages” All these “other” women of Mrs Dalloway tell stories which bubble under the surface, overseen.

In her introduction to The Annotated Mrs. Dalloway, Emre writes “only Woolf’s characters could have shown us the common ground where life and fiction meet: not at fixed point in time and space, but in the recesses of our minds” The novel cannot be read in a vacuum, Emre suggests. You can’t read it and then keep on living as if you hadn’t. Mrs. Dempster, Sylvia and the other women have just as much life in them as Mrs. Dalloway, we just have to follow them and let the world recede outside of the covers of the book.

I wrote this post in preparation for the Literature Cambridge 2023 Virginia Woolf summer school. The series of lectures and seminars looked at some of the women characters in five of Woolf’s works.

your thoughts?